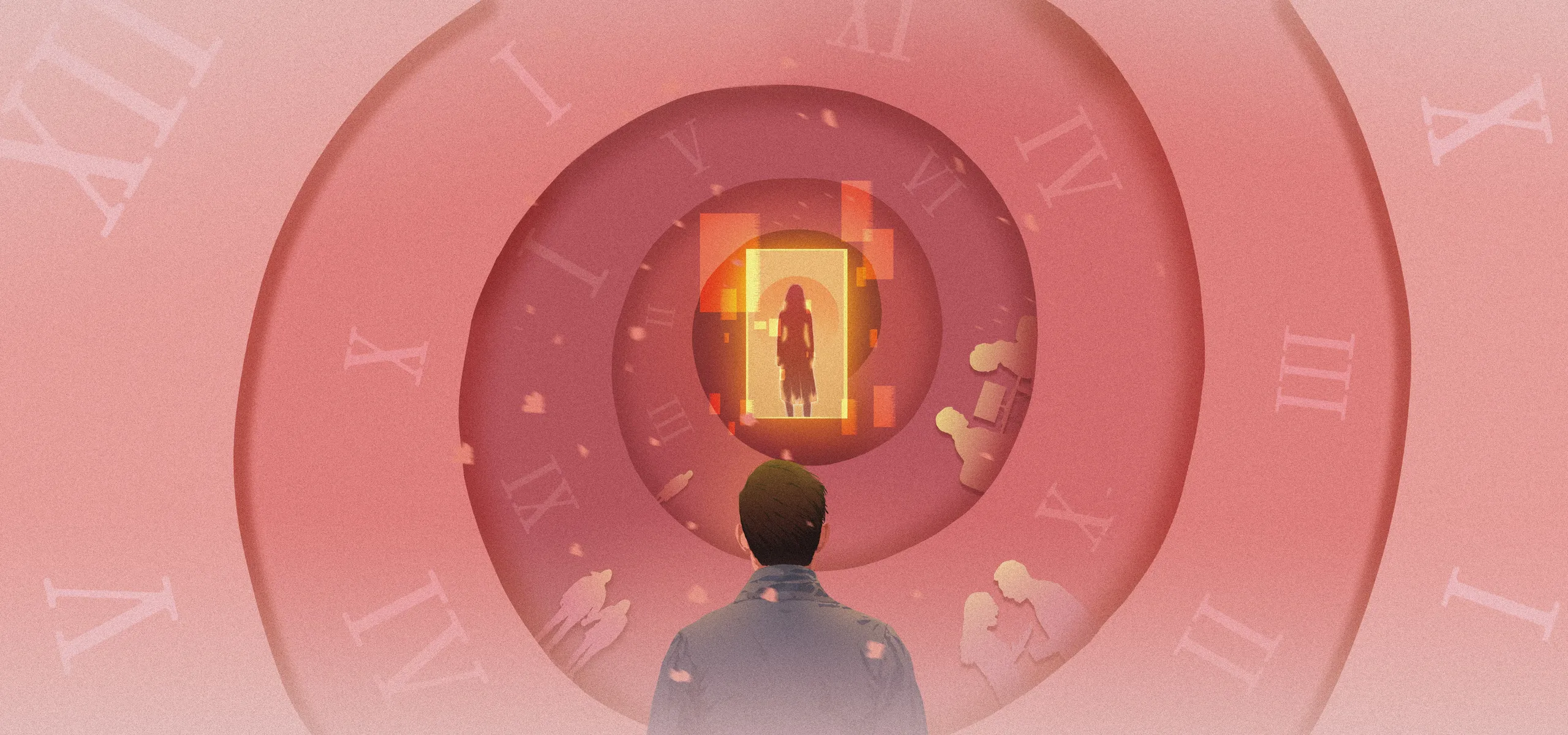

A time-bending tale of love and life from author Li Hongwei

Almost time.

He looks around the room one more time. Three silent bunks. The beds clean, the desks below tidy.

His bed—all in order… Not a single crease in the sheets. The blanket folded into a perfect block.

On his desk, only a computer. Books on the shelf or in drawers. The only items left out are his old white mug, and another, new one. It has a light blue glaze. Two holographic zebras nuzzling each other and whispering. He reaches out his right hand and turns the mug, so that the zebras seem to move. One of their tails swishes. He sees the trace of his last cup of tea inside his white mug. Why wasn’t it cleaned? He takes the cup and goes to the washroom. A knock at the door. He rushes back to the desk and sets the cup down. He pauses, squints, moves it to the other side of the computer, and then takes a longer look. He pushes it in a bit further. Knocking again. Two steps, then back. Feet on the ladder up to the bunk. Pull down the blanket. Finally, two bounds toward the door. He rips the door open on the second knock of the third round.

Five years, eight months, three days later, he pulls the door open on the fourth knock of the first round. Outside the door, there is a solemn, gorgeous radiance. Fourteen years later, he opens the door in the same instant she takes out the key. Unexpectedly, a soft pink haze rushes in. Fourteen years, one month, and twenty-seven days later, she hammers on the door, and he sits at his desk, staring at her on the screen, crouched between two girls. Thirty years later, at around the same time, two minutes to four, he stands in front of the bedroom door, straightens his collar, strokes his cheek, reaches out and knocks. From inside she answers, “What’s wrong?”

“It’s May 15,” he says.

On May 15, at the present moment, he hurriedly wipes his hands dry on his pants, composes himself, and pulls open the door, as if he had never opened a door before. She stands there, in the same clothes she wore when they met in the cafeteria, the same shirt and the same pants. She has put on white sneakers with three dark purple stripes. Later, when he takes her shopping, sees similar shoes in a store, and asks about her pair, she says she has no idea where she lost them. Nine years, nine months, nine days later, she sorts through her closet and finds the shirt and the pants. She holds them up against herself, sighs, and says, “I can’t wear these.” Before he can say anything, she tosses them into a garbage bag.

“What are you doing?” she asks. “It’s taking forever.”

“Nothing,” he says, stepping aside. “Come in.” He pauses. “They aren’t here.” He says nothing more. She hesitates. Fourteen years, one month, twenty-six days later, when she says those words to him, he sees the same hesitation. But the hesitation is more fleeting than it had been at that moment in the present. It gives way to a firmer determination.

“Where did they go off to?” she asks, walking inside, not paying attention to the closed bathroom door or the three other bunks, going right to his desk as if she knew it was his. When she gets to the desk, she stands there as if sizing it up, or as if she is dazed for a moment and surprised to find herself there.

He begins to panic. “Homework, shooting hoops... They went out...” He takes two steps toward her. She turns back. Her expression is inquisitive and probing. He quickly adds: “Sit, sit, please.” He gestures at his own chair. He pulls up the chair from the other bunk. It creaks as he scrapes it across the floor. She frowns. Eight months and one day later, six hours later than the present moment, in the same room, she says, “Aiya!” He turns around in his chair and sees her holding up her right index finger, which has a bead of red blood hanging from it. Leaning toward her across crossed legs, his chair gives a harsh, multilayered creak. She forgets or doesn’t have time to frown at the sound. He takes her hand and inspects her finger. He sits down. He sits back in the chair. She sits back, too. He gets to his feet soon after, and asks, “What do you want to drink?”

She looks at him, tilts her head, and asks, “You got any beer?” A year, ten months, five days later, she waves off the bottle of soda he offers her, tilts her head, and asks, “You got any beer? We should be celebrating.” That day, she drinks three bottles, accepting a toast from all his friends, sometimes by herself, sometimes with him. When they leave the hot pot restaurant, she throws her arms around him for a hug. When he lowers his head, she says, “It’s good, to still be a student.” Without waiting for him to answer, she asks, “Why do you love me?” Four years, one month, one day later, she waves off the cup of tea that he offers her, doesn’t tilt her head, smiles, and says, “You got any beer? Let’s celebrate.”

She watches as he cracks a bottle of Wusu and fills a mug, watching the foam overflow and slip down the glass onto the table. She pauses, waiting for the foam to settle, picks up the glass, and clinks it hard against his. “This is great!” she says. “You’re staying, too.” She takes a sip and clinks her glass against his again. “The place I always want to go.” She finishes the glass. A moment later, she smiles, and says, “I’m not saying I don’t like my job!” She watches him pour two more glasses and asks, “Do you know why I told you not to invite anybody else?” She glances around. She leans forward. He moves, too. But she sits back and shoots him a smile he will remember for the rest of his life.

Thirty-six years, seventeen days later, she faces a room full of friends, and her eldest daughter, in a white wedding dress, and whispers to him, “Pass me that glass of beer.” He waves his hand, motioning his younger daughter not to move. He opens a bottle of beer and carefully pours it into a glass, taking care not to let the foam overflow. He lifts the glass and takes a sip before passing it to her.

At the present moment: he shakes his head, caught unprepared. “I don’t have any,” he says. “I’ll go get some. Is Yanjing okay? Maybe Tsingtao?” She smiles and he realizes that he looks foolish. He scratches his head and asks, “You want a soda? I’ve got tea, too. I think it was Dragon Well.”

“Tea is good,” she says. “I’ll try your Dragon Well.” She takes the mug and twists it around. She stares at the two sets of zebra eyes. “Put my tea in here,” she says. “Pretty neat cup. The zebras are so ugly they’re cute.” She looks into the cup. “It’s clean.”

“Of course,” he says. He loosens up a bit. He takes the cup and one for himself. “I just bought it. This one... I actually use it myself.”

“Do you need to this time?” she says, then stops, and looks uneasily at his cup. “Thank you!” she says. “If not, I wouldn’t be able to use it.” She glances at him.

He is uncomfortable again. Even more than he was before. At last, he could take the cup and go to the bathroom to wash it out. He rinses it out in the sink. Still dirty. He puts it down and scrubs the inside with the tip of his right index finger, then stops. She sits down again and tilts her head to scan the bookshelf. She makes no criticism, nor does she pull out any of the books. He returns and sets the mug down, takes a canister of tea from the shelf, and opens it.

“Strong or weak?” he says, and her expression returns.

“Either way,” she says. “How about you make it the same as yours?” Again: “Oh, right.” As time runs by, these words remain, plentiful and thick, so that what is true and what is false becomes hard to separate, and the meaning and the circumstance are obscure. They slide by in an instant. Naturally, nobody would notice the passing of time, or the speed at which it flowed, nor even the marks it left behind like stains in a mug. So, he does not pause, but carefully shakes an equal amount of tea into both cups. He lifts the thermos and pours in hot water.

“I put the water in this morning,” he explains. “This thermos doesn’t hold heat that well. It’s just right for green tea now.”

“So fine!” she says and reaches out for the handle of the mug.

“That’s what they say,” he says.

Six years, two months, seven days later, she leans over, examines his tea cup, watches the tea leaves floating upright in the water, takes a sip, and smacks her lips. She sets down the cup and goes to open her suitcase. She takes out two cakes of pu’er tea and hands them to him. “Start drinking this. It’s better for your stomach.” She pauses. “That’s what they say.” She adds, “I learned a lot this time. Drinking tea... All different ages… An old expert told me that this suits people like you, who are always attending social events.”

Twenty-three years, eight months, eighteen days later, he sits down beside the tea table, as he usually does, rinses out the cups with hot water, and prepares the leaves. She comes over, as she usually does, and sits down on the sofa, but she holds up a hand to stop him. “I don’t need a cup. Don’t make tea for me at night. I can’t sleep.” And then she says, “It’s strange. I drank tea at night for years and years without any problem, but suddenly I can’t sleep. I’m not sure it has anything to do with tea.”

Tea leaves are still floating on the surface, but they have begun to slowly unfurl in the water, releasing their fragrance. Her nostrils flare as she inhales twice, hard. She blows the tea leaves away from the rim and takes a small sip. “Not bad,” she says, setting her cup down, then glancing over it twice. “This is the first time I’ve come to your place. How are you planning to entertain me?”

“Entertain you? Oh...” He thinks for a moment. “You want to watch a movie or something?” He goes over and turns on his computer. It buzzes to life. “We bought a membership to a streaming site. Have a look to see if there’s anything you like.”

She took a glance. “A membership? You bought that? Why don’t you just download movies?”

“The four of us share it. You have to pay once every six months, and we take turns on that. It doesn’t add up to much.” The computer is on, so she slides her chair over to be closer to the mouse and keyboard. He clicks on the browser and types in the web address. “Downloading is fine, but nowadays, these video sites buy up the copyright, so things can be hard to find.” And then this scene, too—two people, three people, four people in front of the computer or the TV, discussing what they wanted to watch—became concentrated by time, and slipped away, without leaving any trace. They both make their recommendations, yet each picks up their phones, and watches the same video, and, as before, the traces are indistinct.

Thirty years and a day later, he thinks of dinner the night before, the stop-start conversation after returning home, and invites her again. She says, “Let’s skip dinner and go to the movies.” They arrive at the theater, where it turns out they are hosting a retrospective that includes the movie he wanted to show her. Of course, through the movie and during the trip home, he does not mention the past. Lying on his bed, the movie plays behind his eyelids. There is a scene of the hero sitting in a hard chair, watching a pair of flickering hands on a TV set.

The site doesn’t load. He glances down at the network status and sees it’s not connected. He moves the mouse but she stops him. “Don’t bother,” she says. “They’re changing the cables. The whole school is offline.” She picks up her tea cup, sips, and laughs. “Did you know what you were doing, inviting me over today to stream something?”

“Uh.” He feels as if he has been struck by lightning. He takes out his phone. It’s connected to the mobile network. “We can watch something on my phone.”

“No,” she says. “The screen is too small. Two people sitting together holding phones. Is that any way to entertain a guest?”

“I just bought this computer. I haven’t downloaded anything yet. I didn’t get anything off them, either. How about we watch something on one of the others’ computers?”

“That’s no good,” she says. “A computer is more private than a bed.” He goes over to stand in front of the desk, his hand hovering over the power button, then looks back at her. She looks at him, smiling cryptically, but the message to stop is clear enough. He hesitates for a second, then goes to the computer at the bunk across from his. His roommate won’t be angry. But if anything inappropriate pops up on the screen... She stands and sits down in the chair in front of him, takes the mouse, and begins clicking through files. “If the computer is new,” she says, “there shouldn’t be anything inappropriate on it, right?”

He is sure there isn’t. Eleven years, one month, fifteen days later, she picks up his phone as if by accident. “There shouldn’t be anything inappropriate on it, right?” she asks, holding it out to him. He assures her there is not, reaches out a hand, and unlocks it with his fingerprint. She looks at him and hands it back. “You really want me to take a look?” But in the present moment, he watches as she works, following the cursor from My Computer to E:, where she discovers a folder named “Movies.” She opens the folder and finds it empty. “Nothing here,” she remarks, moving back to Start and scanning the programs. Suddenly, she goes back to the “Movies” folder, clicks through the options under View and selects “Show hidden files and folders.” A folder called “New Folder” appears. She looks up at him and smiles devilishly.

Have the guys done anything? Are they hiding anything? He feels a bit of panic, but it’s too late to stop her. He watches as she opens the folder and discovers a movie file called “fantastic four” in MKV format. “Can we watch it?” Double-click. It plays. His throat feels like it is closing. It feels as if he cannot breathe. If they renamed one of those sorts of movies under this innocent title, then...

He hears four drum beats followed by a familiar melody. It eases the constriction on his throat. He can breathe again. Spotlights sweep over a logo that looks like a monument. A comic book outline appears, with the Marvel logo shifting from blue to white. The film company’s name appears, then the title: FANTASTIC FOUR. He pulls over a chair. It appears to be the real thing. But why this movie? He had never watched any Marvel movies, nor had he heard that the three of them might be fans of superheroes. Was the hidden file installed as a gag by the kid that set up the computer, or was it something more innocent?

“You like these movies?” she asks, clicking the mouse to pause. She reaches for her cup. Noticing how she moves, he realizes that she had been nervous before, maybe even more nervous than him...But he is not quite sure of that and the revelation makes him feel guilty. The discomfort he felt over her insistence on opening the files fades away into nothing.

He goes to pick up the thermos and refill her cup. “Thank you,” she says. “I remember you said you don’t like superheroes because none of that stuff is real. If it’s not real, it doesn’t have anything to do with actual life.” She says this two years, ten months, eleven days later. “You really think you’re a superhero, huh? Who the hell do you think you are?” She asks this thirteen years, three months, thirteen days later. After she asks, she stomps on his left toe with her right foot. “You seem to think you’re in a play,” she says. And for once, the scene jumps forward fifty-eight years, one month, seventeen years later. Wait. It jumps back to forty-four years, ten months, four days later, and she is sitting on the edge of the bed, holding out a hand to him, listening to him say the final words, “I can be your hero.”

“Not really... Let’s do something else.” He passes the cup back to her. She takes it, blows the tea leaves away from the rim, and takes a sip.

“There’s nothing else to do. Look at this: I found the rest of the hidden files.” She clicks the mouse.

Welding torches, a dark blue figure, draped in something like a suit of armor composed of silicon chips, holding in both hands what appeared to be models of molecular bonds. “Victor Von Doom likes to build statues for himself, thirty feet tall,” a voice says. The following shot is two heads, seen from behind. The one on the left is bald and the one on the right has longer hair. The next shot is the two faces of the main characters, seen from the front. At first, he doesn’t recognize them. But his attention has been captured. He thinks he might as well sit down.

The film’s plot is simplistic, even childish. He studies the face of the lead actress and realizes from her profile that he knows her from Sin City. He remembers her name is Jessica Alba. But he can’t remember the name of her character. He doesn’t know the names of the other three leads or the actors who play them. He may have glimpsed their faces in other movies, but they are not familiar. He looks over at her. In profile, she looks thinner than the way he usually sees her. He is looking at the right side of her face, which seems softer than the left side. He saw her left side in the cafeteria. The left side had a certain healthy toughness. That was what had pushed him to go over and talk to her. Fourteen years, one month, twenty-six days later, it is the right side of her face that he sees first, before their eyes have a chance to meet, before she says those words.

Her gaze is locked on the computer screen. An omen of something terrible about to happen, the cosmic flow of time shifts, and the clock shows nine minutes, forty-seven seconds. The alteration of time nurtures everything. Jessica Alba’s boyfriend asks for her hand in marriage. But there in the shadows there is a statue of herself. This is a sign that he will go down the road of the village. Let him propose and let her be excited, anyways, even if there’s no chance of any of it coming to fruition.

And then, sure enough, the villain can’t wait for the four words he hopes for. Instead, there are four other words that really will “change our lives forever”: The cloud is accelerating. The world speeds up along with it. The arrogance of the villain is necessary but it is not plentiful enough. A material that resembles aurora lights floats past. Nobody is spared. And then. Just wait. Is this how they saved money on special effects?

“This is good. I want to, too,” he says. These words, he feels as if he has said them before. Was it in a dream? It won’t come true, he knows. “Always the same. If a spider bites you, you become Spider-Man.”

“What superpower would you like to have?” she asks, glancing over at him.

The dream will come true, but he finds he cannot speak. What superpower? He doesn’t even know what superpowers these four have. The movie feels like part of the dream. He decides that he has seen it before. The details are still obscure. “What superpower do you want me to have?” he asks. She doesn’t answer, eyes fixed on the screen.

Five years, eight months, ten days later, he says, “Move in with me.” She gives no answer, but he knows she will. Six years, eleven months, twenty-nine days later, he says, “Marry me.” She gives no answer, but he knows she will. Eleven years, eleven months, twenty-eight days later, when he apologizes to her, she says nothing, but he knows she has not forgiven him. Nineteen years, four months, fourteen days later, he is about to speak but her gaze silences him. In the present moment, she continues to stare at the screen, watching the five face off against their inevitable, strange fates. Are they pretending they don’t know?

He extinguishes this thought. What was the point of criticizing a few actors? Or if he wasn’t attacking them, then he was attacking a few characters in a film. It was clear that this film had not given them the ability to travel through time, and none could see what was coming. “What superpower would you want to have?” he asks. He asks in the present moment. He asks himself. They perform for him: The handsome playboy can control fire, the male lead can bend in improbable ways, the female lead has invisibility, and the tough guy can turn his body into stone. Where is the logic? The tough guy is easiest to understand. Does the handsome guy control fire because he’s hot? Is the male lead mentally flexible? Does the female lead feel as if she is not quite part of the world?

He escapes the screen. “What superpower would you want to have?” he asks himself. What about out of these four? Rock-hard muscles and controlling fire didn’t sound good. When he was younger, he would have chosen invisibility. Now... would he become a paparazzi? Five years, eight months, thirteen days later, he asks himself this for the third time, then hugs her, laughs, and says something that confuses her: “I don’t need anything but what I have.”

Twenty-seven years, four months, and nine days later, he looks at his daughter’s grief-stricken face, and asks himself the question for the fourth time. He knows he needs some superpower, but he is not sure what it should be. Maybe he must first make it clear to himself what is and what is not a superpower. Fifty-eight years, one month, sixteen days later, upon waking, he thinks about this question for the last time. In an instant, he has the answer: “Peace and quiet.” A short time later, he gets his wish.

What if you could move through time? You don’t need to travel through time, but can look inwardly, and apprehend a general picture of future events. You can’t be greedy. You can’t see the whole world. He only wanted to see his own world. He wanted to know if she was still in it. If she wasn’t there, he could try to figure out how to restore her. If she was there, he would need to figure out how to keep her there. “Would you want to have that kind of superpower?”

She makes a noise: “Ah.” But she doesn’t notice it, so absorbed in the screen. A woman in a silk nightgown is almost hit by a car. Her back is seen as she hurries into a building. “Whatever happens, we stick together.”

Could she hear his thoughts? “What?” he asks.

“You didn’t see that?” she asks, her tone a bit annoyed. She glances over at him. “Debbie and Ben said they were going to stick together, no matter what happens. When he became like this, she got scared and ran away.” That was him, the tough guy, called Ben.

“It’s okay. I’m sure they’ll end up together. Don’t all Hollywood movies turn out like that?”

“No way,” she says, shaking her head. “He has to find someone that accepts him for what he is. It definitely won’t be Debbie. That’s Hollywood logic.”

Where were those thoughts running? People should not look deeply into the flow of time. Or what? He shakes his head, too. He gives up on that superpower. The exhibition of their powers is over. The accident is a chance for them to earn some fame. They have uniforms and a name for their group. The villain, though, is beset by darkness, frustration, and failure. Whether he is bound by his wicked nature, evil’s lack of imagination, or more likely the need to develop a plot, his progress down the dark road is played for simplicity. Of course, mixed up in all of this are sublimated impulses and the theoretical clichés. It is all in the standard narrative mold of a superhero story—the rejection of their new identities after a mutation, the obstacles they face afterward, and the attempts to get back to the original state of things.

But no matter how simple the plot is, it still sweeps him along. He follows the plot by noting the change of scenes. The showdown between good and evil tends to produce empathy. Examining the plot again, holding out against it momentarily, he knows that it is simplistic and crude, but he also knows his resistance is simply another product of its coercive power.

What he knows for sure is that those four people have captured his attention and made him forget about her, sitting beside him. Whether looking at things superficially or even more seriously delving below the surface, he didn’t actually forget about her, but had reduced her to some insignificant person sitting beside him. He forgets why he invited her. He forgets how much thought he had expended on it, how he had spent time rehearsing even the simplest greeting. He forgets describing her to them and asking them to leave. He forgets what his tone of voice was, his expression, his posture. He forgets how they felt as they radiated out from him. He even forgets that his ultimate purpose in inviting her to the dorm was to get closer to her. They are adrift in two boats, floating on the River Lethe, surrounded by darkness. They cannot see or remember each other.

It’s actually the perfect metaphor. The village is turned into a statue through the combined efforts of the heroes, echoing his first appearance in the film. His frozen body moves out of time and takes on an eternal sheen. His human desire is locked inside of it, serving as a simple and poignant metaphor. His ability to control electricity also serves as a metaphor: Like the four heroes, his power can only come from primal natural forces. The handsome playboy writes the number “4” in the air with flames, everyone exults in the victory, and the villain is shipped back to the States. A subtitle announces that the story is not yet over. Everyone knows there is going to be a sequel.

“She’s blind,” she says. These words disperse his drifting thoughts.

“She is your projection—”

“She is your continuation—”

“She is your stranger—”

If you go back and point your finger at any node, you can find words that begin with the same two letters, whether light or heavy, happy or angry. The people and events might change. “She” might as well be “he.” So, these paragraphs can be skipped. “This response makes more sense, according to the situation, but it goes against proper ideas,” she says. “Whatever happens, we stick together. He needs to get back what he lost, to compensate for it. It has to be equal, or it doesn’t count.”

Nineteen years, four months, twenty days later, she is willing to talk about her feelings that week, the experience of the previous eight years, two months, twenty-three days, and she begins with the same words: “It has to be equal, or it doesn’t count.” She pauses a long while, until he gets nervous. She says, “That’s how I used to think. Actually, if you’re talking about compensating, there’s no way it can be equal. We have a saying where I’m from: No matter how you stitch it up, it’s still going to scar.”

When she says this, he remembers a line from the Dao De Jing: “Compromising with great hatred inevitably leads to more hatred.” He finally understands that all these things are in the past.

“Not necessarily,” he says. “It depends on the people involved. If she and Ben got together, they might be happy. It doesn’t matter if she can see what he is truly like.” Is he justifying something that has not yet happened and probably never will? Is he laying the groundwork? Not really. It’s just making conversation, hoping that she won’t get up and go, say goodbye to him as she heads out the door. She doesn’t. She picks up her mug and takes a sip. She sets it down and he fills it again. “It’s too bad we can’t get online or we could watch the sequel,” he says. “Maybe, we could use our phones...”

“I don’t need to watch it,” she says. “The sequel doesn’t say anything other than that.” She looks at him again. “You don’t know what your next move should be, so you want to kill time by getting me to watch the next movie, right?”

“That’s not what I—” he starts, and before he can finish, she is standing and walking out onto the balcony.

After six, the sun is still hanging on the horizon, turning the western sky red. The balcony glows with the same color at a lesser intensity. She holds the railing and looks down. A few people rush by, headed for the cafeteria. He wants to go up to her, but, staring at her back, he hesitates. Through the afternoon and the movie, he sits beside her, but he doesn’t feel as if he knows anything more about her than he did before. He still yearns more than ever to be close to her. He has never desired another person this much.

A bit closer. From where he is looking, she is framed in the doorway like a number “1.” Ah, Fantastic One. As he thinks this, he seems to see the flames ignited by the handsome playboy rolling before his eyes, the tough guy tossing around a glacier, and the rubber man reaching out to block it, to stop the ice from melting. At the peak of the glacier, Jessica Alba steps out of invisibility. And so, he walks toward her.

As he steps through the door, it disappears, and leaves her standing there. He is sure: She is the fantastic one, the only one that matters. He pauses, waiting for the clouds of cosmic energy to pass by and stir something in her. This cosmic current comes so powerfully and quickly that its power flows through her and then jumps to him. He receives its power. And so, he steps forward, stopping a few steps from her, watching her.

“What’s wrong?”

She turns. He is about to speak but then cannot find the strength. He must draw on what he has. He is with the handsome playboy and the tough guy and the rubber man and Jessica Alba, watching the glacier melt and the waves roll down the mountain—and he leaps at her. “I am the fifth superhero,” he blurts. One of five. This is the only way that he can convince himself.

“What?” She looks at him. She realizes in an instant. “What’s your superpower?”

“What’s your favorite flower?” he asks.

She smiles. “Peach blossoms!”

Watching her smile, he moves toward her, silently repeating to himself: “It is this time! It is this moment!” His wish comes true: As he plants his foot on the second step out onto the balcony, he steals the sunset glow and turns into a peach tree. The trunk is strong. The branches reach out. The blossoms, tightly bunched, bloom among the tender leaves. Each flower turns to face her. They bloom with her smile. That’s not enough. On the branch nearest her, the blossoms move aside to reveal a flower bud. No need to force it. Just watch. Just her breath is enough. It opens. It blooms—petals stretching out on top of one another, as if it will never stop blooming, as if there will always be room—into a red rose.

Fantastic Five | Short Story is a story from our issue, “After the Factory.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.