Jia Pingwa’s ‘The Sojourn Teashop,’ now with a new English translation, is a bold experiment for an author often lambasted for his characterization of women

In the spring before the pandemic, Jia Pingwa invited me to Xi’an to talk about a translation of his novel, The Shaanxi Opera, which I was close to completing. For me, it was a chance to creep (under supervision) around the studio of a master. In the small amount of space not taken up by ancient curios and books—among them, a few collections of Eileen Chang—I discovered a few sheets of loose-leaf manuscript. Later, I found out it was an urban novel—about women.

Jia Pingwa, born 1952, is one of the biggest names in contemporary Chinese literature, widely considered a peer of Mo Yan, the first and only Chinese writer to win a Nobel Prize in Literature. Sitting on top of many domestic and international literary awards, he writes observantly and prolifically, often depicting the lives of common people and, through them, insights on humanity as well as a changing Chinese society.

The book resulting from the manuscript I saw, The Sojourn Teashop, is inspired by the women that often gathered in the tea shop that once operated in the same building as Jia’s studio. I wondered if perhaps this was a response to the accusations of misogyny that had plagued Jia his entire career.

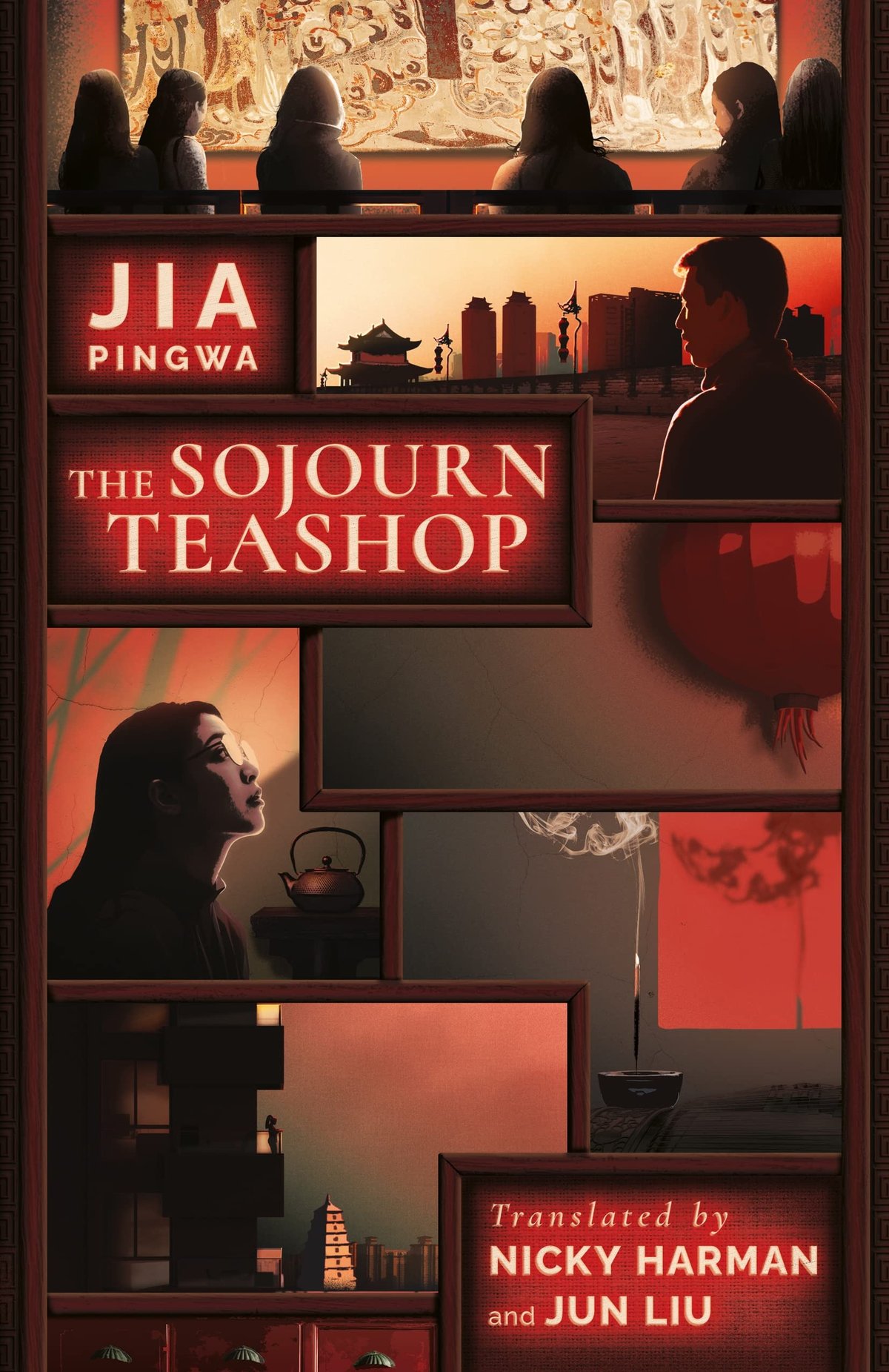

Sojourn, originally published in 2020 and now with a new English translation from Sinoist Books by Nicky Harman and Jun Liu released this February, begins with a young Russian woman arriving in the city of Xijing (Jia’s usual pseudonym for Xi’an) from St. Petersburg. Her point-of-view defines the novel, along with that of Yi Guang, a male celebrity writer that could be read as a stand-in for Jia himself. But the book is less about them than it is a group of 11 women nicknamed at various times “the Sisterhood” and the “Eleven Pieces of Jade.”

The narrative is anchored by Hai Ruo, who runs the titular teashop, but each woman takes her turn at the center of the action, as the group bicker over business arrangements, gossip about friends, or scheme to grease the gears with the local bureaucracy.

Crises crop up—a contact in the government arrested for corruption, the delayed visit of a Living Buddha, one sister dying of leukemia and another disappearing on a trip abroad—but they resolve anticlimactically. Even the novel itself ends with the unsolved mystery of the destruction of the Sojourn Teashop in a bomb blast. This is an example, perhaps, of another frequent trope of Jia’s: the guaishi, or “strange event,” a startling occurrence that is never adequately explained, or which defies rational explanation.

Unlike Jia’s last significant return to urban settings in Happy Dreams, a 2007 novel about trash collectors centered on the urban proletariat, Sojourn focuses on the middle-class. The women run car dealerships and restaurants, drink Lafite with dinner, and cruise around in Land Rovers and Porsche Cayennes. Their lives revolve around consumption and are otherwise somewhat empty; religion and family are diversions. As a portrait of contemporary urban life and the quiddities and agonies of the middle-class, Sojourn is superb.

But it is clear that Jia’s ambition is beyond that; he is also trying to fathom a discrete feminine universe. Jia says as much in the afterword to the book: “[Women] were a world entirely of their own, their ravines as deep as our peaks were high, their waters holding as many fish as our clouds sheltered birds.”

Jia has written, especially in the second half of his career, stories and novels with fully-realized women, but they are outnumbered by his more notorious works of one-sided characters. Women exist in these novels to satisfy the desires of men—for sex, for someone to listen to their witty remarks, or to play the subservient partner in a marriage.

Sojourn reminds one of a gender-swapped version of his controversial 1993 classic Ruined City. A masterful work that blends erudition and profanity, it is, however, a perverse celebration of mature male sexuality, padded with affairs between distinguished men and their younger paramours.

The country girl Tang Wan’er, for example, despite being a sympathetic character, becomes a vessel for an older writer’s passion and seduction, without much time given to exploring her emotions. A mole on her labia gets a more loving description than her inner life.

Broken Wings, his 2016 novel about bride trafficking in rural Shaanxi, in particular touched off a wave of criticism for its perceived misogyny. In the book, the portrait of the trafficking victim—the daughter of migrant workers in the city kidnapped for sale as a bride into a rural area—is moving and clearly written with sympathy, but some feel that it is undercut by the sympathy for the men who condoned the trafficking. Some read it as a celebration of a backward way of life that normalizes the objectification of women, charging Jia with having “morbid nostalgia for the countryside.”

I faced this myself when translating The Shaanxi Opera with Nicky Harman. The women in the village, ranging from blind widows to schoolgirls, are frequently the focus of the story. Men, including the narrator, are mostly on the periphery, but the lives of the women in the book still revolve around them. They can mostly be broken down into the types that Jia prefers: the virtuous victim, the matriarch, or the promiscuous schemer. As a translator, I have no mandate to turn Jia into a feminist, but I know this will restrict the appeal of the book to foreign readers.

The volumes of Eileen Chang, of whom Jia is a long time fan, on Jia’s desk might have been evidence that he is learning to figure out women from a more feminine perspective. Chang is excellent at her closely-observed depiction of women, where chit-chat around a mah jong table can reveal everything one needs to know about the relationships of the players. The flash of a diamond ring under electric light, the tug of an earlobe, the texture of a skirt—these poetic details become means to decipher the social and psychological state of the characters.

Jia’s women and Chang’s women are quite similar in their social status but not in their worldview. Ji Jin, a professor of literature at Suzhou University who reviewed Sojourn in an article for Contemporary Chinese Literature Studies journal, noted the parallels and divergences between Chang’s Bai Liusu in Love in a Fallen City and Hai Ruo, the teashop owner: two divorced, single, aging women of respectable social standing, the former takes a gamble on a relationship with a wealthy bachelor, while the latter “seems comfortably detached and unconventional, not looking to settle down.”

The difference between the lives of the two women might reflect the social progress in China in the 77 years between the works—the avenues open to Hai Ruo were closed to Bai Liusu, restricted by social norms, the guidance of her family, and the imperative to remarry—but, somehow, the inner life of Hai Ruo and her sisterhood also seems more barren.

“The flock of chattering women might be beautiful, but they have no souls,” sneers one commenter on review platform Douban, where the book has earned a lower rating than any of Jia’s previous work. ”Throughout the novel, they each remain like sheets of paper: vague, blank, and unreal.”

It’s unclear whether Hai Ruo’s blankness is due to Jia’s stylistic choice to leave much unsaid in his characterization, a critique of the emptiness of modern life, or a lack of understanding of women on his part.

The same Douban comment is cynical about Jia’s intention of gathering a group of women in a teahouse around a scholar: “Old men all want to write about the world of women.”

In Jia’s 1995 essay, “On Women,” he brought up the idea of tai (态), referring to the posture or bearing that embodies a traditional sense of femininity—in other words, traits that make a woman attractive to men. He elaborates that for prostitutes who “lived off of men, like an appendage” to “become equal to men, and self-sufficient,” the key is to “have the correct tai.”

This idea echoes 25 years later in Sojourn through the words of Yi Guang, who explains tai as “the essence of a woman” to his interlocutor Xin Qi, a member of the sisterhood.

“It’s like the light emanating from the Buddha, the flame of the fire, the gleam of precious stones or jade,” he adds. And to demonstrate his approval of Xin Qi’s tai, Yi compares her to a rose, before he “reaches out, in spite of himself, and pinches her nose.”

The character should not be taken as the author, nor depiction for endorsement. But Jia has sometimes made following these rules difficult. Responding to the controversy around Broken Wings, in a 2016 interview with Beijing Youth Daily, though Jia denounced trafficking, he defended a compassion attitude for the buyers of trafficked women: “If these men do not buy wives, the village will become extinct.”

Jia is not Yi Guang, but they might suffer from the same limitations: They are both men of a certain generation, raised in a context different from that of, say, typically younger Douban users. Among China’s great contemporary male writers, however, Jia does not stand out as particularly chauvinistic. Yu Hua, for example, known for his dark sagas that realistically relate the plight of China’s underclass, has often been criticized as writing only docile women with soft personalities. Many young readers also find female characters in Liu Cixin’s science fiction Three Body Problem trilogy to be unconvincing, pointing out they’re either saints or moral degenerates.

The sensitive translation by Harman and co-translator Jun Liu deserves the final note. Read against the original, it is arguably an improvement. As Douban commenters have pointed out, the unpolished, contemporary language of the women in the book is sometimes clumsy (one compares Jia’s attempt to China Central Television’s Spring Festival Gala hosts awkwardly deploying internet slang), while Liu and Harman’s colloquial British English makes the dialogue come across as more authentic.

Despite the limitations of Sojourn, it is one of the most fascinating books in Jia Pingwa’s late-career oeuvre, a bold experiment by an author that has no pressure to take chances. The translation gives it new life and, hopefully, a wider audience.

Full disclosure: The author is a professional translator who has been involved in the publication of one translated novel and one essay by Jia Pingwa.

Can One of China’s Most Famous Authors Shed His Reputation for Misogyny? is a story from our issue, “After the Factory.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.