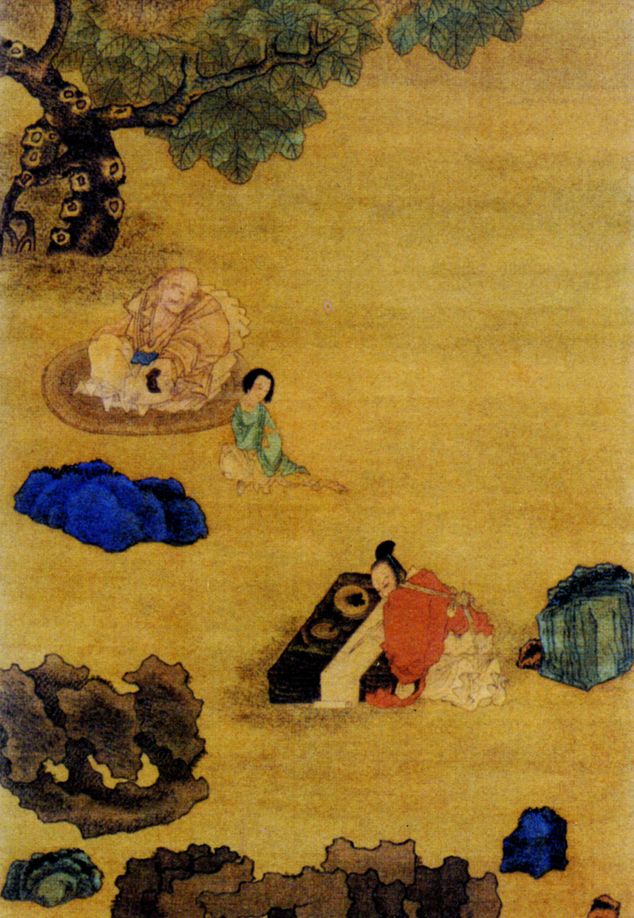

Ancient Chinese consumers had to watch out for all manner of frauds and fake goods

Rotten pickled vegetables found in instant noodles, men posing as female live-streamers to scam money, “sweet potato starch” made of cheap cassava, exploding electric bicycles...

Another year, another long list of scandals. Many more will be exposed during the annual “3.15 Gala,” a two-hour television show hosted by state-run China Central Television every March 15, World Consumer Rights Day. The show has become an annual social event (almost like the Spring Festival Gala) for viewers and netizens who revel in predicting which companies will be named and shamed, and then lambasting them for their shady practices.

Yet for all the attention this contemporary campaign garners, China’s history of fighting against (as well as producing) fake goods dates back thousands of years.

As early as in the Western Zhou dynasty (1046 – 771 BCE), the government had already begun to oversee the quality of goods. According to The Book of Rites (《礼记》), a Zhou dynasty text that set guidelines for appropriate behavior, “unripe grains and fruits,” ”trees that are not fully grown,” as well as "beasts, fish, and turtles that are not fully grown or properly cleaned” were not allowed to be sold.

In the Warring States period (475 – 221 BCE), the earliest law on fake goods appeared. Canon of Laws (《法经》), China’s earliest systematically written code of laws, regulated that anyone who sold fake medicine would be flogged, and if any death or injury was caused by the counterfeit products, the seller would be exiled.

Penalties became even harsher in the Qin dynasty (221 – 206 BCE). People who sold fake medicines could face punishments ranging from tattooing the face with black ink, cutting off the nose, cutting off a foot or toes, castration, and even decapitation.

In the Han dynasty (206 BCE – 220), as the economy developed and the Silk Road promoted trade, fake goods became more common. Laws proliferated too: regulations stated that rotten food shouldn’t be sold in the market, once found, it should be burned, and if it caused any poisoning, both the offender and government official in charge should be punished.

However, because of the huge profits involved, strict laws didn’t stop people from taking their chances. During the reign of Emperor Wen, a major forgery case even deceived the emperor. According to Records of the Grand Historian (《史记》), official Xinyuan Ping (新垣平) was adept at counterfeiting. Once he faked a jade cup with an inscription on it reading: “Long live the emperor,” and ordered his subordinates to offer it to the emperor, claiming it was found in Fenyin (in today’s Shanxi province). Then, Xinyuan said to the emperor that it indicated the lost Zhou-dynasty ding would be found in Fenyin.

The ding was a huge three-legged bronze cooking vessel, which was believed to be cast on the orders of legendary king Yu the Great. It then became an important symbol of imperial power, so obtaining the ding had a symbolic significance to the emperor. Believing Xinyuan’s words, the emperor ordered for temples to be built in Fenyin for worshipping the gods. Before too long, a ding was found as predicted. As you may have guessed, it was actually a fake buried previously by Xinyuan. The truth, however, was also unearthed in due time, and Xinyuan, together with his parents, brothers, wife, and children, was executed.

In the Jin dynasty (265 – 420), a major forgery case shook academic circles, which involved The Book of Documents (《尚书》), one of the Five Classics of ancient Chinese literature which was believed to be created in the Zhou dynasty and served as the foundation of Chinese political philosophy for over 2,000 years. In the Qin dynasty, when Qin Shi Huang, the first emperor of a unified China, burned books and persecuted scholars, the book was almost destroyed, with only part of the texts preserved by scholar Fu Sheng (伏生), who lived until the Han dynasty.

This part of the texts came to be known as the “Modern Script.” Also in the Han dynasty, Kong Anguo (孔安国), one of Confucius’s descendants, discovered another part of the texts in the wall of the family’s estate. This new material became known as the “Old Script.” However, the Old Script was lost again in the chaos of the Eastern Han dynasty (25 – 220).

In the Jin dynasty, a government official named Mei Ze (梅赜) offered a volume of the Old Script to the court, claiming it was the version that Kong Anguo had found. he government accepted the story, and the volume circulated widely. In the following dynasties, the book was viewed as one of the most important classics for scholars to read. However, from the Song dynasty (960 – 1279), people began to suspect that this “Old Script” was fake, because compared with the Modern Script, it seemed much easier to comprehend. Many scholars then began to investigate its authenticity. In the Qing dynasty (1616 – 1911), scholar Yan Ruoqu (阎若璩) collected over 100 pieces of evidence, proving that the widespread version“Old Script” was actually fabricated.

In the Song dynasty, the commodity economy was well-developed and civil business prospered. Accordingly, fake and shoddy goods became more rampant. In the Recollections of Wulin (《武林旧事》), a Southern Song dynasty (1127 – 1279) text, author Zhou Mi (周密) recorded many scams, including making clothes with paper, faking silver with copper and lead, and making perfume with dirt and wood. These dishonest merchants were referred to as “daylight thieves (白日贼).” The food industry was hit particularly hard. Scholar Su Xiangxian (苏象先) recorded in his book Lessons From Premier Su Song (《丞相魏公谭训》) that a store in the capital Kaifeng stewed horse meat with fermented soy beans and sold it as roe or venison.

Swindlers in the Ming dynasty (1368 – 1644) were no less creative. In his book On the Virtuous and the Wise (《贤博编》), author Ye Quan (叶权) accused the city of Suzhou of having many false goods in the market. Ye wrote: “Sellers carry loads of flowers, which look colorful and beautiful, but none of them are real; The red bayberries were dyed into purplish black with ink; Stick a long tail on a hen, and it will be sold as a pheasant.”

In the Qing dynasty, even government officials had become victims. Anecdotes in the Qing Dynasty (《清代野记》), an unofficial historical text believed to be created by Zhang Zuyi (张祖翼), recorded a swindler nicknamed “Cha Fei Tian (插飞天).” He and dozens of his followers roved all over the country, impersonating high-ranking officials to extort money from local officials.

The battle against counterfeiting seems to be an eternal and even futile struggle. Indeed, as an old saying goes: “when the priest climbs a foot, the devil climbs ten.” But at least we can take solace in the fact that as the “3.15 Gala” approaches, another batch of unscrupulous marketers will pay the price.