How an artist couple tugs at the loose threads of society—by working with their own hair

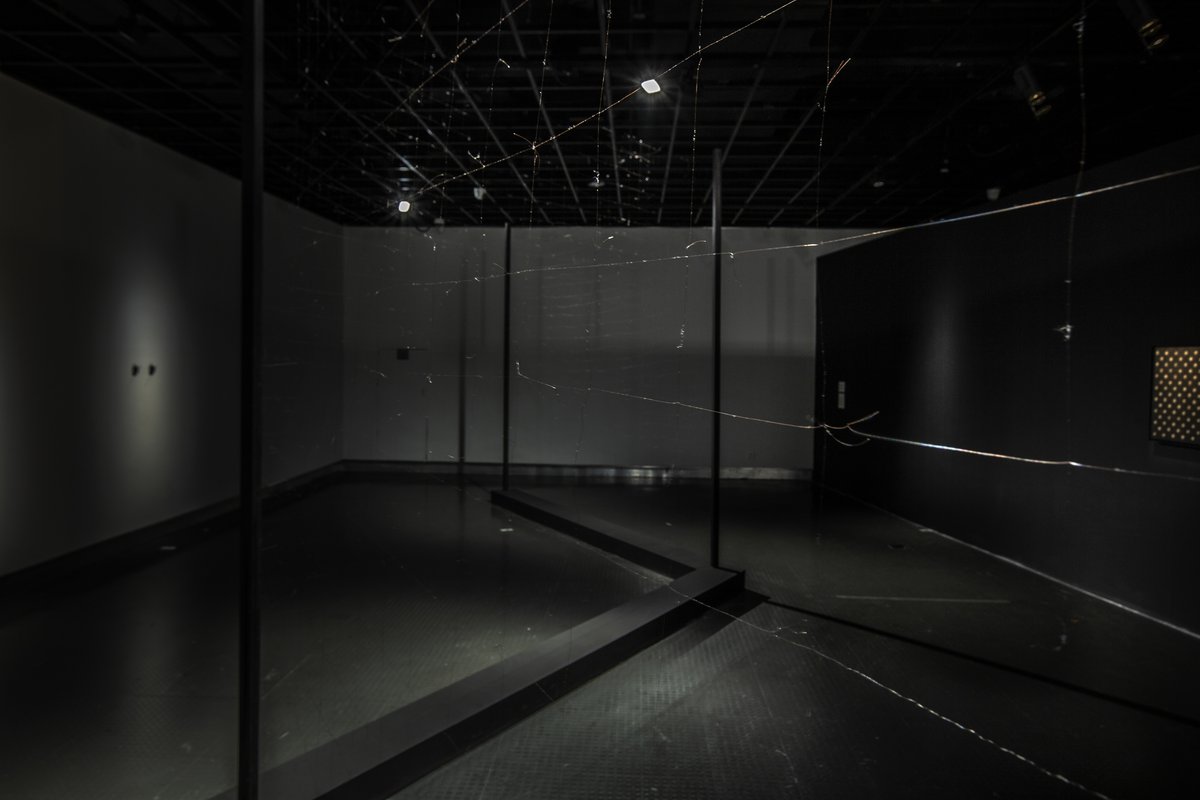

The gallery corridor seems almost too empty for visitors to know where to rest their gaze.

From afar, nothing but a few dark wooden columns stand guard of the space. Only at an intimate distance, under certain angles of light, does a flimsy fence reveal itself—extremely thin strings knotted into square grids, stretching to fill the space between the columns. It is not immediately clear what this prickly fence, with stray ends of the thread sticking out from the knots, is trying to separate. At a glance, it’s doing nothing but collecting dust, almost stubbornly asking to be lost from sight.

In early 2020, artist couple Lin Yi and Shi Bing constructed this fence with their own hair. During the early phase of the Covid-19 pandemic, as the pair was confined at home in Hangzhou with very little income, they started collecting the objects they found most often around the home—fallen hair and dust—to create art that reflected on the experience, especially taking note of the sense of isolation that had just begun to plague the country. The fence (titled in English “Being Together While Illusional Separating”) is part of a 12-piece collection coming out of that period, along with a set of two single-handed clocks with the tip of their points connected with one thin hair and an office chair tufted with hair.

Many of these works are not much to look at, especially in the middle of a jungle of towering head shots, blinking lights, neon-colored optic fibers that sprawl across the floor, and the entire room covered by statements sewn on flags—all clamoring for viewers’ attention at the Hangzhou Triennial of Fiber Art housed at Zhejiang Art Museum, where some pieces from Lin and Shi’s collection, including the fence, were last exhibited from October to December 2022.

But it would be a shame to mistake this odd fence for a mere palate cleanser in between scenes of razzle-dazzle. Viewed near the end of 2022 as China’s strict pandemic control protocols swiftly dissipated, the piece struck home on another level. The combination of its arbitrariness and fragility—it quivers when passersby so much as breathe on it—is also reminiscent of the man-made, sometimes over-the-top quarantine measures, which asserted themselves with such authority but later faded almost overnight.

For the two young artists, the work offers a glimpse of how they use art to engage with ambiguity and the zeitgeist. Born in 1989 in Fushun, in the northeastern Liaoning province, Shi embarked on his artistic journey when his father, an art-loving soldier, brought home stacks of art books. Around the same time, Lin’s father, a former bun shop owner and self-taught graphic designer in Chaozhou, in the southeastern Guangdong province, took her to study in the home of a teacher at the only art college in town. Eventually, Lin and Shi both found themselves opening up to the conceptual side of their vocation at the China Academy of Art in Hangzhou, where they studied fiber art as graduate students.

Having hailed from the two far ends of China to tie the knot (and knots) in Hangzhou, the pair chats with TWOC over a video call—from a messy couch strewn with coats and art supplies, as they were in the process of moving to a new studio in a more affordable part of town. They speak about hair, their creative process and understanding of art, and their career as young contemporary artists in China.

“I am still quite lost. My edge is that I have yet to find a path in art,” Shi says, shrugging to the camera. Lin, sitting next to him at ease, elbow propped on his left shoulder, chuckles in self-recognition.

What was it like working with hair?

LY (Lin Yi): I see hair as a very intimate material, because it bears our DNA. It keeps growing as long as we are alive. While it is indeed quite delicate, I don’t find working with hair particularly demanding. Coming from a fiber art background, I like making knots, both orderly ones and random ones, and turning them into art pieces.

After every shower, we would each take a white plastic bag, and tousle our hair to collect the clean strands that fell out. We have both been a bit of a hoarder. I get a haircut about every two years, and I keep the clippings. Shi Bing collects his dead skin, and he keeps his clipped nails in a glass jar, even when he travels for work. Maybe he’s just curious, wondering how many years it would take to fill up the jar.

Are you planning to use hair to create more artworks?

SB (Shi Bing): There’s a bit of continuation, but we might move on to something else. The choice to use hair back then had resulted from a change in our creative concept.

We got so sick of “PowerPoint art.” Around that time, we had little luck submitting our works to exhibitions. Some experienced artists told us it was because our PPT slides were not good enough. Nowadays, you often see influencers who check out art exhibitions mostly for taking photos using the works as a backdrop. Everything needs to be pretty, to present visual tension. But we wanted to make works that you cannot grasp by just looking at photos of them. You would have to be in front of the work to feel it. The idea was to “de-visualize,” to create something you cannot see very easily.

Another reason behind the de-visualization is that at the time, I felt quite stressed out and helpless about many things. The frail, almost nonexistent quality of the work must have had something to do with that.

I had a similar idea even earlier: a performance art piece, drawing a thin sewing thread across the Qiantang River, to create a contrast to the Qiantang River Bridge. This thread is like myself, reflecting how an individual exists in the macro—you can say it’s fragile, or dispensable, but it does exist. When thread floats in the wind, it’s even more poetic than the massive concrete bridge.

Now that the “zero-Covid” policy is over, how do you feel when you look back at this group of works from the beginning of the pandemic?

LY: I thought that period was quite nice. We didn’t have to go out to work, so we had undivided time for ourselves, for making art.

When you are confined to the very intimate space of your home, your senses are heightened infinitely. Maybe you realize you’d never carefully looked at every corner of your home. Or you discover more spots you have to clean. Your observations become more nuanced, and the way you think is more grounded.

SB: I am happy with this group of works, but they are limited to the context and conditions of that time. If you place them in the world as it is now, it’s not quite the same thing. We can’t just keep on exploiting the concept or relying on it as an identifier of ourselves.

LY: Many artworks came out of that phase of the pandemic, but my eyes hurt from looking at them. They were full of big heads of experts, masks, or shows of power. It made me wonder why isn’t there a better way to comment on the circumstances through art.

In your other works, have you always been so critical toward today’s art world?

SB: Not deliberately. Well, we haven’t really made our way into the “art circle,” so how can we criticize it? Personally, I’m more interested in critiquing social problems.

LY: I am more on the intuitive side, not so eager to criticize. My work usually focuses on the everyday, and on the materials themselves. But if a social event touches me deeply, it makes me want to speak up through art.

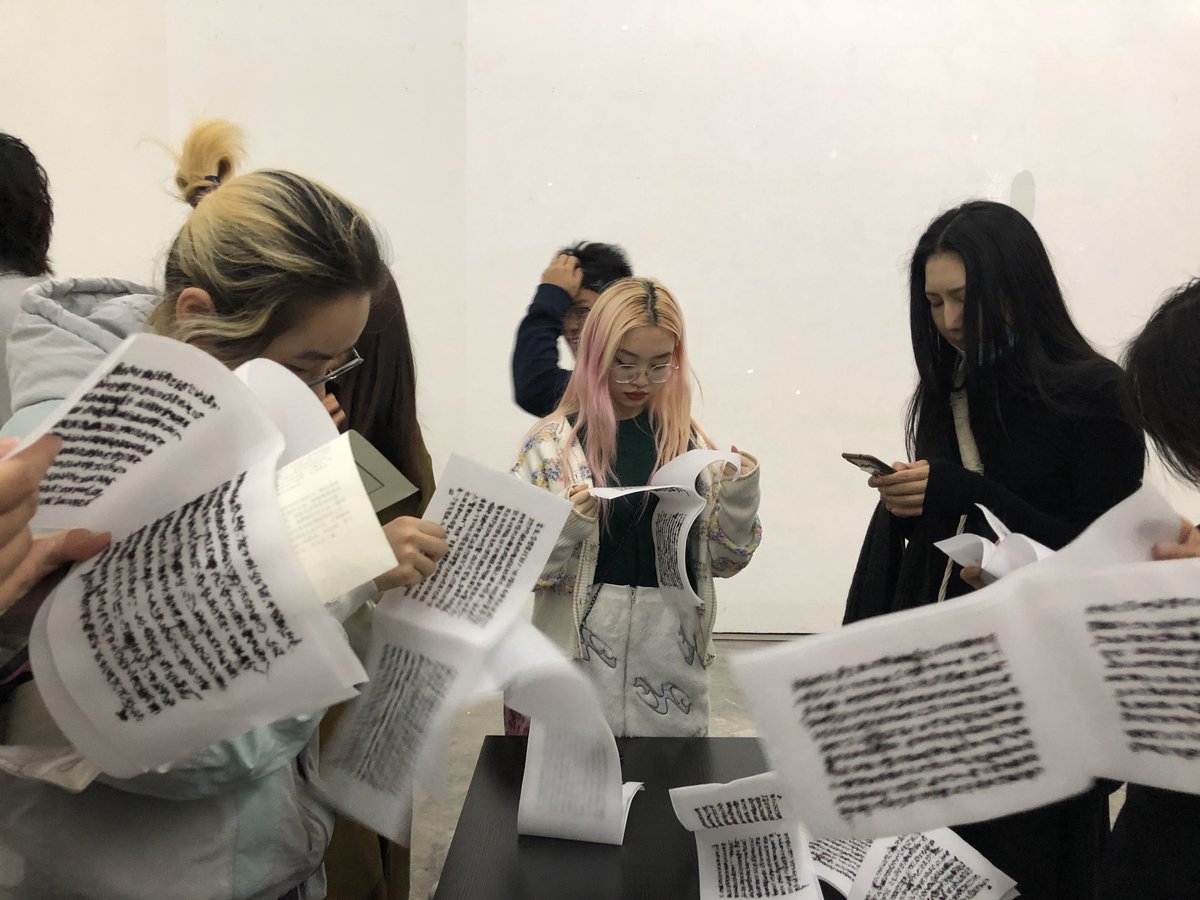

For example, I once made a book with Velcro patches, and in between the hook side and the loop side, I embroidered texts that told the story of businessman Bao Yuming’s alleged sexual abuse of his adopted daughter. This was a high-profile case around the end of 2019. It went viral on social media, but only for a few days. Our society’s news cycle is so rapid that there are always new breaking stories covering up old ones.

As a woman, I am struck by the violence in the story. In my artwork, it is also a forceful process to rip open the book, with the lacerating sound, all mirroring sexual violence. But then, as more and more people open up the book to read, the information gradually disappears under the friction of the Velcro, as if the event ceases to be important.

How do you think the discipline of fiber art has influenced your work?

LY: I usually don’t introduce myself as a fiber artist. Our discipline is still quite niche. People have begun to talk about fiber art exhibitions in recent years, but previously, they would ask, “What do fiber artists do? Knit sweaters?”

As an undergraduate I studied sculpture and focused more on the visual outcome and style. Every course was about teaching you a technique; there wasn’t much about “creation,” per se. But at graduate school I started to realize that the things I want to express matter.

But every year, I see graduation exhibitions at the academy, and feel a sense of horror—many works are so similar, repeating the same ways of wrapping, weaving, knitting. Alarmed, I thought I should try to keep some distance and not assimilate.

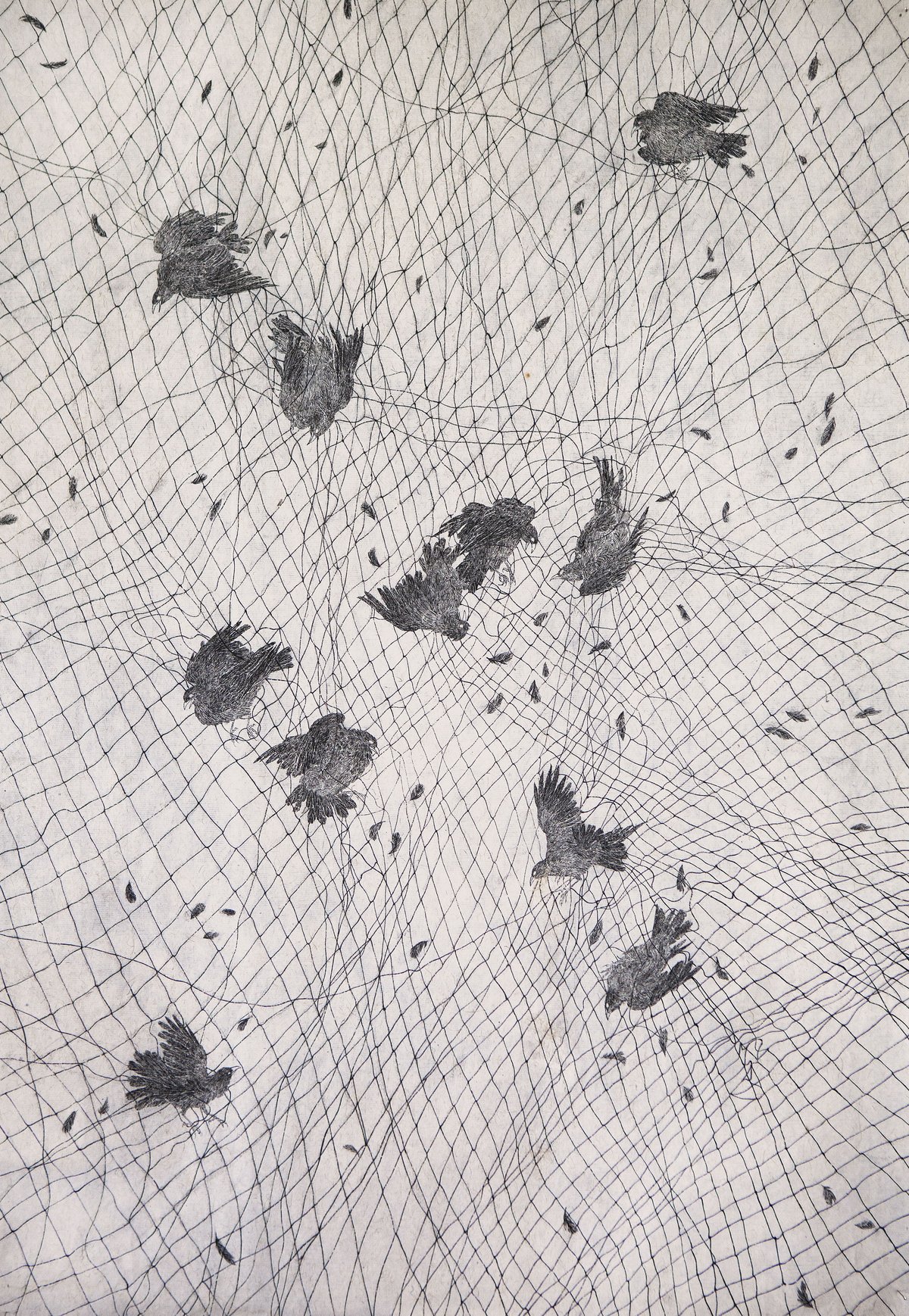

SB: I see fiber art as a decentralized way of working. You can start with a small section, without knowing what the result will look like, and extend infinitely from there, and it can grow like a plant. Unlike painting or sculpture, you don’t have to start by constructing the big picture.

One work that really inspired me at the triennial was a set of red screens showing different scenes, taken from submarine cable landings around the world. These cables are not “threads” that we can see, but they intimately affect our lives. The work helps us perceive in a metaphorical way that these threads have also knitted a big net that we cannot escape.

Shi Bing has previously mentioned in interviews that his art is focused on the moment of creation and not on the result. Could you both share how you understand process-oriented art?

SB: I used to see my work as process-oriented, but then, what on earth is “process-oriented?” When it turns into an easy way out for artists who are not really equipped to reach an artistic result, it becomes a problem.

The notion of “process instead of result” is also now quite a platitude, especially in contemporary art. If you follow a certain formula, you can arrive at a piece of process art. But that process is already predetermined.

I am not now trying to deny the value of process, but I’ve grown wary. Perhaps we shouldn’t be too obsessed with this dichotomy. The way I see it now, it’s more important to examine how you approach and think about your own creation.

When I read about social issues, I am constantly reminded that maybe the problem lies in the way we are used to doing things. Can we really apply unchanging ways to evolving problems? That applies to art too.

LY: I still quite enjoy the process. Because I spend a lot of time weaving and knotting and it is highly repetitive. Many might see the work and find the almost robotic process boring, but I like boring. And I like highlighting the monotony…I see “process” as a way to cultivate inner strength.

Images from Lin Yi and Shi Bing

The Young Fiber Artists Tying Themselves in Knots is a story from our issue, “Kinder Cities.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.