A century ago, the founding of a children’s magazine witnessed a progressive movement in how modern Chinese society wrote for—and saw—children

In 1923, Ye Shengtao (叶圣陶), an intellectual who had recently begun writing for children, attached a note of caution to his latest submission to his editor: “Perhaps you might not find it ‘childish’ enough?” His manuscript told of a compassionate scarecrow who helplessly watches an elderly farmer, a fisherwoman, an abused wife, and a carp all suffer misfortunes in front of him, and eventually collapses in the field due to the crushing guilt and despair he felt.

Such a dark tale may not be classified as children’s reading in China today, where parents have tried to ban the classic novel Outlaws of the Marsh (《水浒传》) and even the Xinhua Dictionary for having content inappropriate for minors. But for Zheng Zhenduo (郑振铎), the founder and editor-in-chief of Children’s World magazine, “The Scarecrow” was exactly what China’s new generation of children should be reading. The story became Ye’s most influential work for how it captured a mature sorrow toward social injustices in the language of children, and the magazine itself went on to weather two decades of change—reflecting a wider progressive movement in how modern Chinese society saw children, and leaving its mark on Chinese children’s literature for decades to come.

Children’s World was the first magazine for Chinese children to feature original content written in vernacular Chinese as opposed to classical language. Zheng, who had been a textbook and magazine editor at The Commercial Press (also TWOC’s parent company) before he founded the magazine, was jaded by what he saw in children’s publishing at the time. “Before, education for children was like an injection, aiming only to fill their head with all kinds of rigid knowledge, rigid disciplines…There were too few books driven by children’s reading [habits],” he declared in a “Children’s World Manifesto” distributed by major periodicals before the magazine’s inaugural issue in January 1922.

Young readers who closely followed the magazine in the decades to come would have discovered many delights to fill what Zheng called a “gap” in Chinese children’s publishing: In the year 1927 alone, for example, the content ranged from a biography on Mahatma Gandhi, to a letter between two children discussing the difference between sensations (感觉) and emotions (感情), to a fable of a chicken convincing a crow to flee from war (spoiler: the arrogant crow was killed by enemy soldiers who couldn’t find any chicken left to eat).

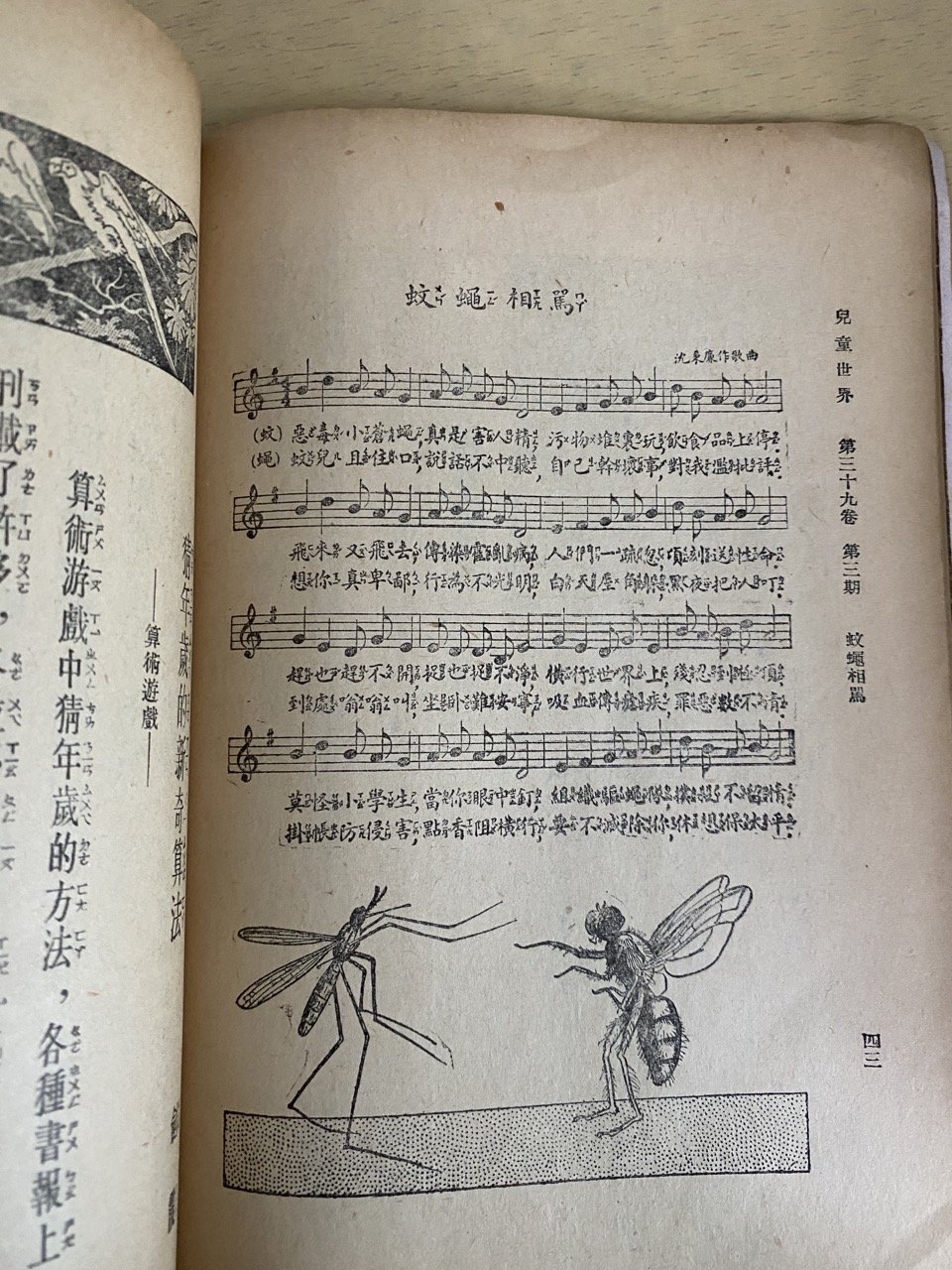

The magazine aimed to cover every aspect of children’s lives and satisfy their curiosities. Its special “Hygiene” issue in July 1927, for example, includes an explanation of belly buttons and constipation, an illustrated poster on eye protection, and a song from the perspective of a mosquito arguing with a fly. In 1934, a special issue on Southeast Asia discussed not only the circumstances of the Chinese diaspora there, but also the customs of indigenous peoples, taking special care to remind young readers, “We cannot despise them based on our own biases, and see them as barbarians.”

Zheng Erkang (郑尔康), Zheng Zhenduo’s own son, was among the captive readers. Though born during the tail end of Children’s World’s publication, Erkang spent considerable time as a little boy devouring cartoons drawn by his father or immersed in the crafts section to figure out how to turn a sorghum stalk into the shape of an animal or a piece of paper into a boat. “Sometimes father came to my aid,” Zheng Erkang wrote for China Reading Weekly, a newspaper about books and publishing, in 1997 at age 59. “He was like a magician.”

However, Lu Xun (鲁迅), arguably the most quoted writer and opinion leader from early modern China, was somewhat dismissive of the magazine in his 1926 essay “Twenty-Four Filial Children.” “Every time I see pupils so enthralled by a copy of something unrefined like Children’s World, I think of how exquisite children’s books in other countries are. Naturally, I feel bad for children in China.” But to some extent, this proves that Zheng Erkang was not an outlier, and that the magazine was indeed a success at least among its intended readers.

Known for his biting wit, Lu Xun reserved the bulk of his ire for earlier children’s literature in Chinese history, such as the 14th century’s Twenty-Four Filial Exemplars (《二十四孝》), a collection of stories whose sole purpose was to preach filial piety. Other reading materials for children in ancient China such as the Three Character Classic (《三字经》, sets of three-character rhymes about history which kids today still memorize, was similarly stiff and moralistic,

Zheng’s decision in 1921 to start a new kind of children’s magazine did not happen in a vacuum. The early 20th century was a time of many cultural and political changes to free China from the feudal system and old ideologies. Many intellectuals turned their attention to “liberating children.”

While Lu Xun is known for his 1919 essay “How Do We Be Fathers Now,” in which he indignantly called for parents to abandon the parent-child hierarchy so essential in Confucianism, his oft-overshadowed brother Zhou Zuoren (周作人) was also at the forefront of this movement. Zhou felt it was absurd that society saw children only as miniature adults ready to drink up the classical canons. In a 1920 lecture at Beijing’s Kongde School, a prestigious co-ed secondary school named after French philosopher Auguste Comte, he advocated for education that followed children’s interests and needs and respected their own agency and independence, instead of “touting conformity in poetry, promoting patriotism in stories, or only thinking about the future.”

Children’s World embraced this ethos by trying to produce content in language and formats friendly to children, often involving generous amounts of illustrations. In a 1937 issue, in trying to engage readers in a brief history of Palestine, writer Zhang Dashan (张达善) opens the article with, “Little friend, in the past few months, have you often noticed the name Palestine in the newspaper? Do you have any questions about this name? Would you be willing to learn about its meanings?”

In the beginning, Zheng Zhenduo did most of the work himself, from drawing the cartoons to writing the stories. But he began to seek help from his friends at the newly founded Association of Literary Studies, whose members included Zhou, Ye Shengtao, and Bing Xin ( 冰心), a female writer who later became perhaps China’s best-known children’s author. “Many who didn’t write for children before were dragged into it,” Zheng Erkang recalled in his 1997 article. In particular, he says that Ye only began writing children’s stories under Zheng Zhenduo’s invitation to contribute to Children’s World. Ye’s contributions began with dreamy tales with idealized natural settings and characters who were pure and kind, before he came up with “The Scarecrow.”

Ten years after its publication, Lu Xun lauded “The Scarecrow” for “chart[ing] a new path for China’s children’s stories,” but lamented that “there weren’t any transformations from that point” among Ye’s own works, nor did anyone else follow up with anything equally innovative or biting. “[Children’s publishing] turned backward” toward virtuous tales, wrote Ye Shengtao’s son Ye Zhishan (叶至善) in My Father’s Long Long Life, his 2004 biography on his father.

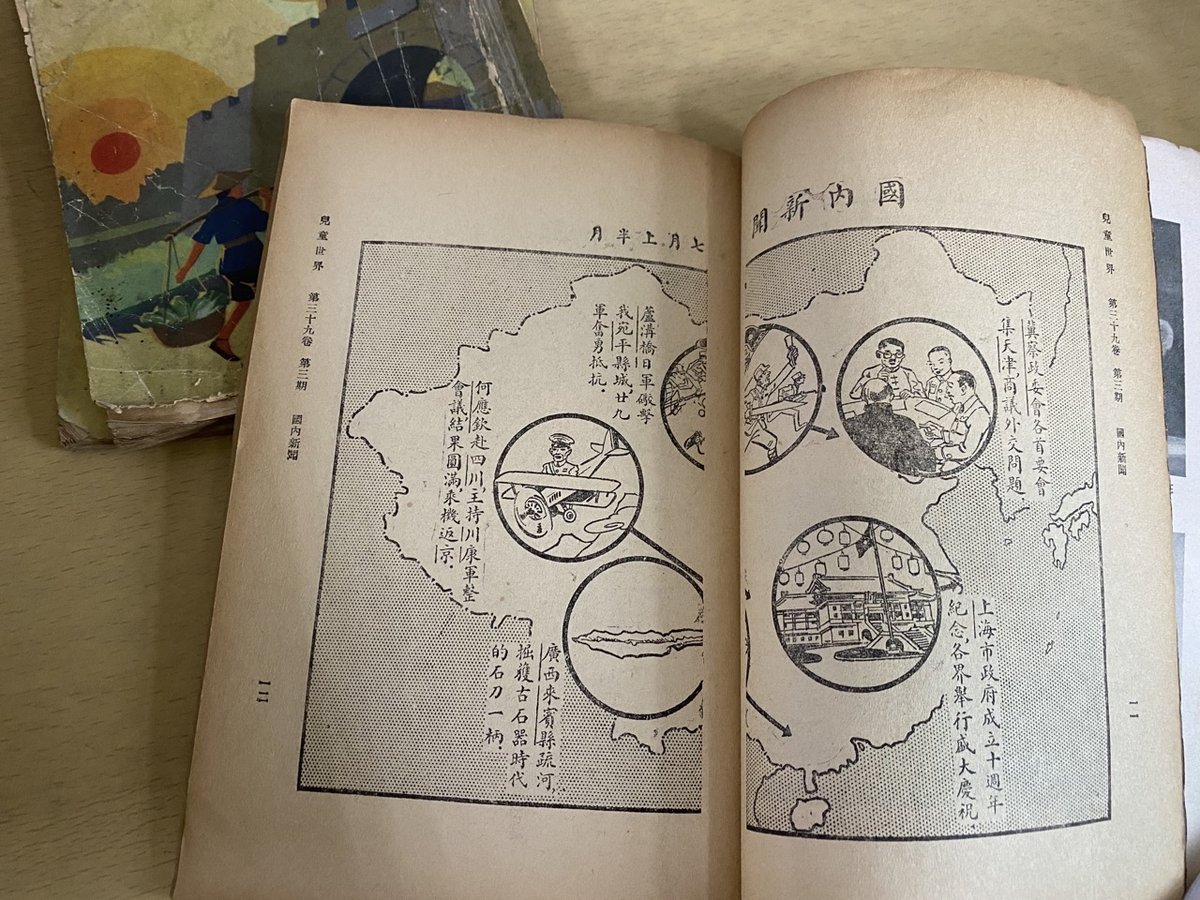

As its young readers and writers grew, Children’s World also evolved. Opening an issue from 1937, it’s immediately noticeable that, compared with a decade before, there was more urgency to engage with current events. The issue opened with the news of the Lugou Bridge Incident, an important event in the war against Japan, and inserted an article about how to protect oneself from poison gas. Even children’s submissions showed traces of patriotism in the 1930s, with the magazine publishing a poem by a fourth grader called Tian Lianxiang in 1934, asking rhetorically if their fellow Chinese should “cave in or make sacrifices,” in the face of invaders.

Some scholars, such as Yang Weitong in his master’s thesis at Harbin Normal University, argue that during this period, with chief-editorship long handed over to Xu Yingchang (徐应昶) since 1923, the magazine had moved from “child-centered” to “national-salvation-centered” as the country fell into a deepening crisis.

As early as 1923, Zhou Zuoren criticized patriotic content for children via Little Friend, another children’s magazine founded a few months after Children’s World and still printing today. It had printed an issue promoting “Chinese-made goods,” possibly a response to the then-ongoing nationalist movement in protest of the 1919 Versailles Treaty, which failed to oust colonial powers from China. Compared to Children’s World, Little Friend was the favored publication of Zhou’s own boy, and published content like nursery rhymes and children’s plays. “I am against putting a political opinion of a time into childish minds,” Zhou wrote in his critique. “Our hope for education was to raise a child as a ‘person’ with integrity, but the education now wants to turn him into a loyal and obedient citizen—this is terribly wrong.”

During the war against Japanese invasion, Children’s World moved offices from Shanghai to Changsha and then Hong Kong, but eventually stopped printing in 1941. Copies lucky enough to survive the turbulent decades to follow are growing dusty and brittle in the Commercial Press archives.

Now, 100 years since the magazine’s founding, parents and experts are still debating what makes a book suitable for children. In recent years, Chinese parents called on authorities to ban textbook illustrations that inappropriately portray children’s crotches—but also a sex education book for promoting homosexuality, and Outlaws of the Marsh for depicting immoral behaviors and condoning violence, among many other works.

To the complaint against Outlaws, however, the Department of Education of Zhejiang Province responded in an open letter to parents, “Outlaws does not show us a ‘correct’ world, but a diverse world, where virtues, vices, and the give-and-take between the two...every move carries the complexity of humanity...which is why we (including children) should read it over and over again.”

Photography by Siyi Chu

The Infancy of Children’s Literature in China is a story from our issue, “Kinder Cities.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.