Hold your breath for one of China’s most underrated goddesses, a murdered concubine who became a patron of toilets and injustices against women

On the 15th night of the Lunar New Year, while some in China go out to enjoy the various festivities surrounding the Lantern Festival, others spend the night on the toilet to take care of important business—not the kind usually spoken about in polite company.

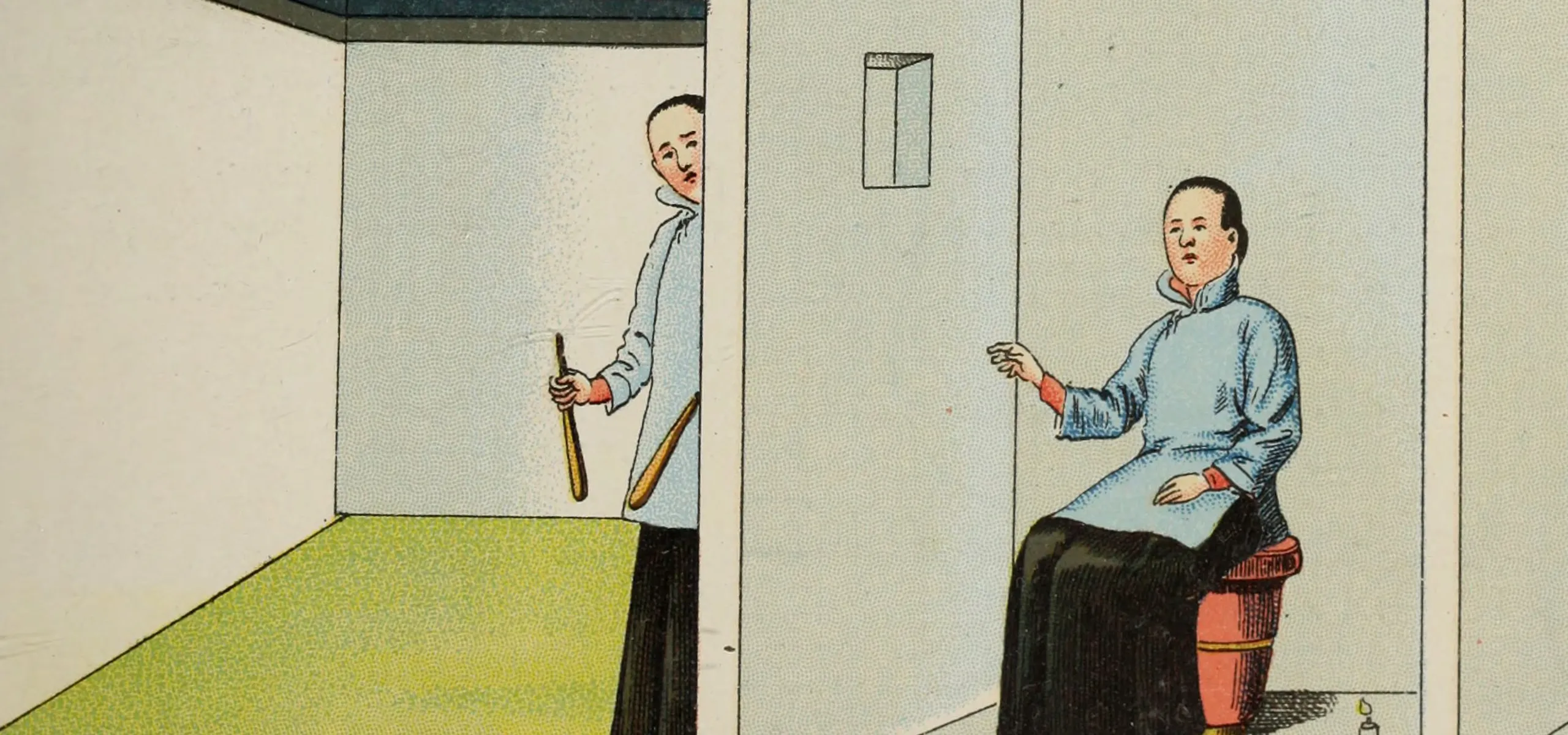

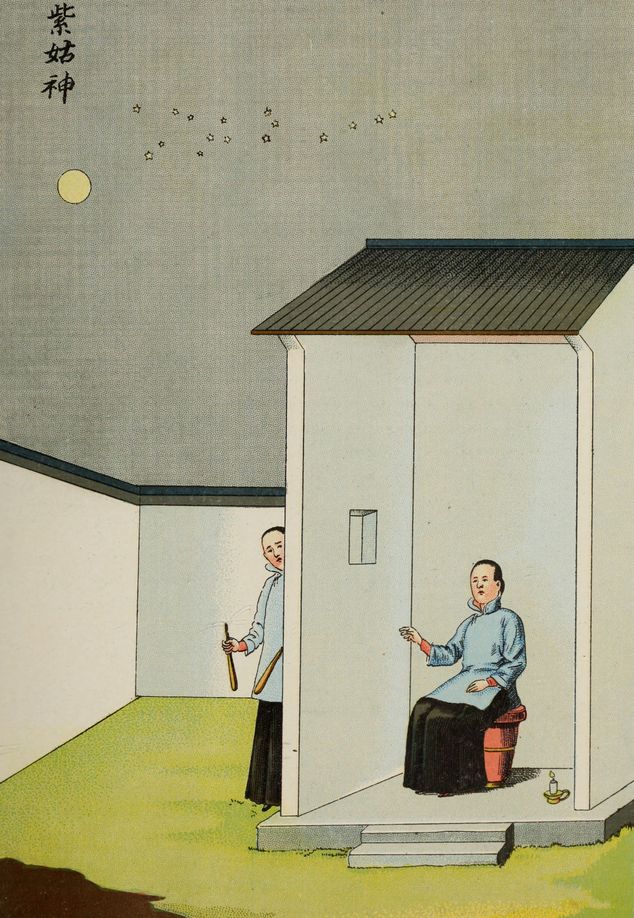

Traditionally, on this night, people clean up their outhouse and perform rituals to welcome an important guest: Zigu (紫姑, “the Purple Lady”), the mysterious toilet goddess who descends to reveal the family’s fortune through spirit writing.

If you were to visit Beijing around this time of year in the Ming dynasty (1368 – 1644), you might spot women putting paper faces and skirts on hay figurines, making them hosts for the goddess. During the séance-like ritual, after the crowd prays to the goddess with horse dung, drums, and songs, the figurine finally comes alive and gestures to answer questions about the future—as recorded in the Ming book Survey of Scenery and Monuments in the Imperial Capital (《帝京景物略》), which documents Beijing’s urban environment and customs at the time.

From the family farm’s yield, to the silkworms’ health, and the weather of the coming year, people around China, especially rural women, have trusted the toilet goddess’s prophecy on all kinds of domestic matters, as various local historical records indicate. In these records, the dates of worship and names used to address the goddess varied slightly from place to place (including “Third Lady of the Pit” in Shanghai and “Maiden of the Shit Vat” in Ningbo), while she often wrote her verdict (on a bed of rice or dust, or by knocking the table) with a chopstick attached to a woven dustpan.

Nowadays, however, other than in spooky childhood memories, the practice of welcoming Zigu has almost died out. But even though the toilet goddess’s popularity might have been flushed down the drain, her turbulent story has captured many generations’ imagination.

In the most widespread narrative, Zigu was born in the Tang dynasty (618 – 907) as He Mei, a well-read young woman in what is Shandong province today. Her fate took a bad turn in the year 688, when a prefectural official by the name of Li Jing killed her husband and forced her to become his concubine. Driven by jealousy, Li’s wife eventually killed He Mei in the toilet on the 15th night of the first moon.

The famous Song dynasty poet Su Shi (苏轼), or Su Dongpo (苏东坡), claimed that Zigu personally told him her story. “Even after death, I dared not complain. But the gods saw my fate, and to right the wrong, they gave me a job serving the human realm,” she goes on to explain in writing via a chopstick wielded by a woman surnamed Guo, stated Su in his essay “Story of the Zigu Goddess.”

But this account likely contains a degree of creative license. The earliest mention of Zigu can be found in A Garden of Marvels (《异苑》), a book of supernatural tales from the Song era of the Southern and Northern dynasties (420 – 589), so the original Zigu could not have been born in the Tang dynasty as Su claimed. This early version does not assign Zigu a specific identity, though the man she married is called Zixu and his wife Lady Cao. While Lady Cao also forced Zigu to perform dirty chores, this version of the goddess was not murdered but died of anger.

This version of the story also highlights how to put the traumatized deity at ease: by chanting, “Zixu is not here, and Lady Cao has gone home. The little maiden can come out.”

Many literati speculated Zigu is not just one person, but perhaps a collective of tragic concubines who suffered from maltreatment. “The so-called ‘Zigu Goddess’ is many in number,” He Mei confesses in Su’s essay—without forgetting to add, “But none are as outstanding as me,” referring to her own ability to write elegant poems.

Another famous lady might be among the ranks of unfortunate Zigus: Lady Qi, the adored concubine of Liu Bang (刘邦), the founding emperor of the Han dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE). The Records of the Grand Historian (《史记》) claims Liu’s empress Lü Zhi (吕雉) was so threatened by Lady Qi that after Liu passed away, “Lü had Qi’s hands and feet chopped off, eyes gouged, and ears burned deaf, muting her with poison, dumping her in the latrine, and calling her ‘human pig.’” In many regions of China, the Toilet Goddess is referred to as Qigu (戚姑, or “Lady Qi”).

It’s not quite clear why the task of predicting domestic affairs falls on the tragic Toilet Goddess, but speculations abound. Some scholars believe the lowly beginnings of Zigu make her relatable to commoners. Women, who suffered many injustices in patriarchal feudal societies, were the main practitioners of Zigu rituals.

Others see Zigu’s humble abode as an important connecting point between death and new life. “Feces signifies death (of the animals and plants eaten, as well as decay); it also signifies reincarnation (as plants flourish with the help of rotten matter)...” Liu Qin, a scholar at Sichuan Normal University who publishes prolifically on both Chinese goddesses and toilet culture, writes in a 2020 meta-analysis on academic studies on Zigu, pointing out the significance of the outhouse in an agricultural society.

Many legends give examples of Zigu directly using excrement for her canny schemes: In Collection of a Useless Gourd (《坚瓠集》), a Qing dynasty (1616 – 1911) anthology of unofficial histories and folklore, the Toilet Goddess, dressed in yellow, dabs some feces behind a man’s right ear, enabling him to understand the language of ants, from whom he then learns about treasures buried underground.

However, assuming a goddess who suffered so much injustice to be entirely benevolent would be blindly optimistic. For example, Tang dynasty literatus Liu Zongyuan (柳宗元) wrote a fictional story of a vagrant named Li Chi. While traveling, Li, who is married, flirts with a local woman, who turns out to be a “toilet ghost.” Li’s friend soon finds him hugging the latrine vat and smiling eerily into it, and despite his friend’s attempt to save him, Li ends up dead with his head in the bowl. During a talk at Taiwan’s Chengchi University in 2011, American sinologist William H. Nienhauser connected the story to Zigu, as a revenge narrative in which she “punishes men susceptible to her seduction.”

What’s more satisfying is perhaps when Zigu comes back to haunt her own perpetrator, who is called Li Jing in Su Shi’s version of the story. In the Ming collection In Search of Supernatural (《搜神记》), after He Mei’s death, whenever Li Jing does his business, “he often hears sounds of crying and even soldiers yelling.”

As Zigu rises from a small-time goddess mostly worshiped by women in the outhouse, to a muse whose fate inspired various literary creations, perhaps her evolution in classical literature tells us more about the time and lives of the writers than about Zigu herself. “Su dramatizes Zigu’s deplorable fate while praising her talent,” writes Liu Qin, the toilet culture scholar, analyzing “Story of the Zigu Goddess” in a study dedicated to Su Shi’s shifts of mindset through his six works related to Zigu. “This pervasive empathy and effort to build a tragic figure is essentially based on Su himself,” who at the time had just been demoted from his job as an official and exiled from court.

But around the same year, Su cranks out another essay, mocking Zigu (hence probably also himself) as lacking real talent and only producing “empty and rotten works.” Years later, as Su had acquired a certain equanimity about his fate despite suffering further demotions, he wrote about Zigu again, but only discussing her as a folk belief without connecting her story to his own.

In today’s China though, the Toilet Goddess seems like a lost cultural symbol of a bygone era. A search for Zigu across many social media platforms only returns lists of Lantern Festival traditions that contain a mention of her name, or fragments of her stories.

One of the very few accounts of a real-life experience of Zigu tradition comes as a memory from a netizen claiming to be born in the 1980s, who comments under a blog post about eastern Zhejiang’s “Maiden of the Shit Vat.” The commenter recalls seeing strokes of writing materializing on beds of rice, as older girls in the neighborhood performed the rituals. “I thought it was so magical,” the comment reads, “that I squatted in front of the pit for hours without finding it stinky.”

In urban Shanghai, people closed the lid on this tradition in the 1930s, while the practice lasted until the 60s in surrounding rural areas. In Haiyan, a nearby county in Zhejiang province, where Zigu is referred to as “Maiden of the Washing Basket,” the tradition died out around the 50s, but the local government is now trying to honor it as a cultural heritage.

In 2015, a village in Haiyan hosted a ritual, with young women in heavy makeup holding up a basket for both a photo-op and a public Q&A session with the goddess. According to a blog by a local writer, spectators from the crowd asked about their silkworms, rice fields, and new businesses. The goddess allegedly returned with vague symbols, which spectators then unanimously interpreted to have auspicious meanings.

While revived rituals, stripped of a sense of awe, seem like a formality only to confirm good fortune, the “toilet revolution” happening in China is also altering Zigu’s realm for good. Starting in 2015, the Chinese government has been rolling out a plan to rebuild rural bathrooms to make them cleaner, healthier, safer, more convenient, and more “civilized.” Between 2018 and 2022, the country renovated more than 40 million rural toilets, according to Xinhua.

But as more rural families now sit on sparkling porcelain toilets, while modernized agriculture relying on fertilizers increasingly severs the toilet-to-farm connection, the ladies and maidens of the pits and vats are losing both their habitats and relevance. “Toilet deities and toilet cultures are inevitably turning into ‘intangible cultural heritages.’ There’s no turning back,” writes Liu Qin, lamenting the fate of Zigu. “From this perspective, studying the Toilet Goddess and the culture surrounding her is like an urgent rescue mission.”