From toys for children to weapons of war, ancient inventors sent many things into the sky

Emperor Shun, a legendary ruler of way back when in Chinese folk belief, had a tough childhood filled with mistreatment from his father and stepmother, but that might have made him the first in China to attempt to fly.

According to Records of the Grand Historian (《史记》), one day Shun’s father ordered him to repair the roof of their barn, but as soon as Shun climbed up, his father lit the barn on fire. In order to survive, Shun jumped from the roof while holding up two big bamboo hats, and landed safely.

Shun’s hats might not qualify as the first parachute, but he was not the only ancient Chinese to attempt to fly (or at least fall with style). With hot air balloons in the news recently, it‘s worth remembering Chinese inventors have churned out flying contraptions for centuries, from soaring kites to intricate bombs used in war.

Egg balloons and hot lanterns

“Burning Chinese mugwort can make an eggshell fly,” says the Huainan Encyclopedia of Ten Thousand Technologies (《淮南万毕术》), a Western Han dynasty collection describing phenomena in chemistry and physics by Daoist Liu An (刘安, who is also often believed to be the inventor of tofu). Balloon enthusiasts around the world have not reached a consensus on whether hot air balloons as we now know them have Chinese roots, but this text at least shows that about two thousand years ago, people in China more or less understood the basic principle.

People sending off a giant Kongming lantern in Jieyang, Guangdong province, on Mid-Autumn Festival, 2015 (VCG)

In China, however, this principle lead to the important creation of the Kongming lantern (孔明灯), a paper lantern with rosin burning inside on its bottom plate. The hot air from the flame helps the lantern fly up high, just like a balloon.

There are two versions of the how the lantern was invented. The more popular version attributes it to Zhuge Liang (诸葛亮), also known as Zhuge Kongming (诸葛孔明), a famous politician and strategist of the State of Shu in the Three Kingdoms period (220 – 280), hence the name. Like the story of many cunning inventions, this folk legend starts with a predicament. When Zhuge’s troops were besieged by the enemy, he ordered soldiers to make a thousand paper lanterns and use smoke to fly them into the sky. Then the soldiers shouted together: “Mr. Zhuge fled on the lanterns!” Distracted, the enemy ran after the flying objects, giving Zhuge’s troops a chance to successfully break out of the siege.

The lesser known—but more reasonable, some argue, as paper-making was not yet ubiquitous in Zhuge’s time—version says such lanterns were invented in the Five Dynasties (907 – 960) by Shen Qiniang (莘七娘), whose husband was a military general. Folklore has it that, when Shen was in Fujian, where her husband was fighting a war, she made such a flying lantern to send signals to friendly forces. Since the shape of the lantern resembled Zhuge Kongming’s hat—imagine a tall and upside-down bucket bag—it became known as a Kongming lantern.

In ancient China, Kongming lanterns were often used on the battlefield. New Treatise on Military Efficiency (《纪效新书》), a military manual from the Ming dynasty (1368 – 1644), recorded that famous military general Qi Jiguang (戚继光) had used Kongming lanterns in different colors to give out various signals, in order to direct operations against Japanese invaders.

Eventually, people in China also adopted the practice of sending off these luminous high fliers to pray for good luck, especially on the Lantern Festival and Mid-Autumn Festival. Nowadays, fire departments in China advise residents against it for safety reasons. But outside China, the practice is still alive. In northern Thailand, every full moon on the 12th month of the Thai lunar calendar (usually in November), locals and tourists release thousands of lanterns into the sky.

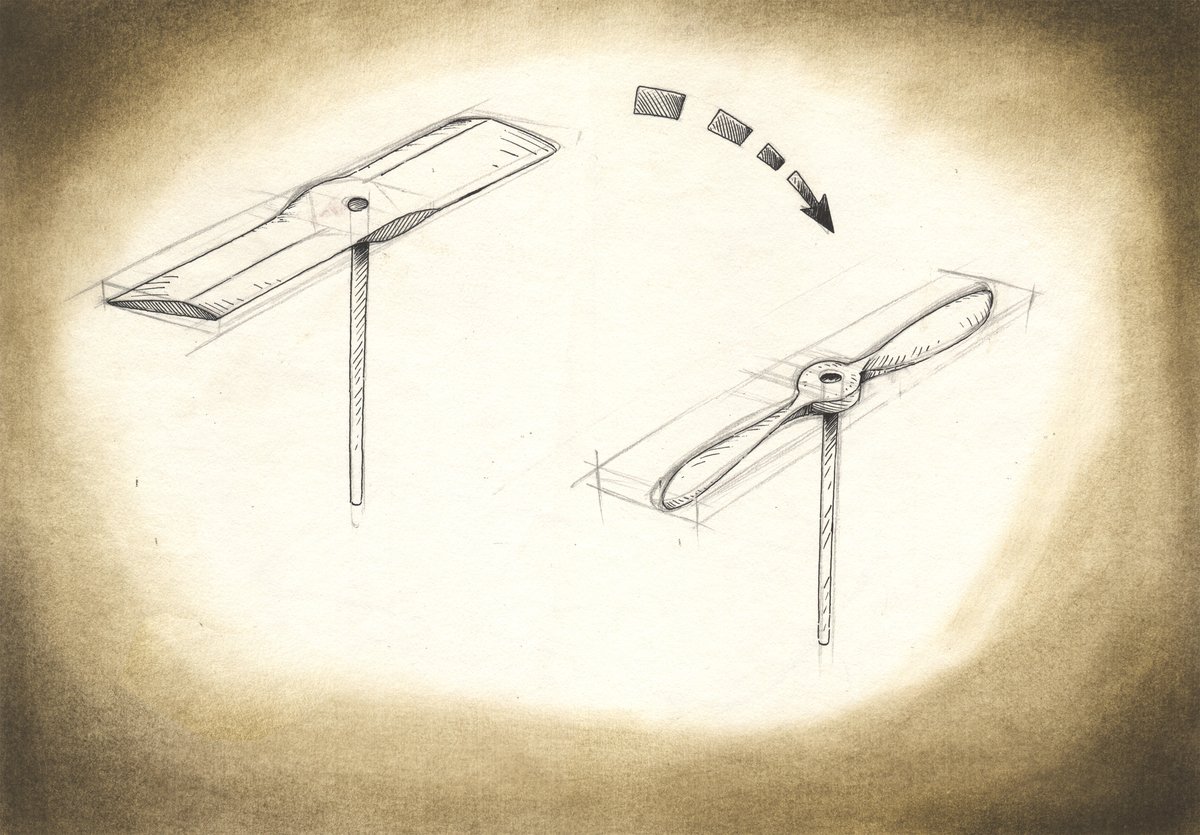

Bamboo dragonflies

The bamboo dragonfly is a simple but ingenious toy believed to be invented in the Spring and Autumn period (770 – 476 BCE). This T-shaped object is made up of a thin bamboo strip attached perpendicularly to the end of a stick. When the stick is rapidly spun between the palms, the bamboo strip works like a propeller and carries the bamboo dragonfly through the air. Though in China it remains just a toy for children, the bamboo dragonfly, known as a “Chinese flying top” in the West, is commonly believed to have become an object of fascination for 18th and 19th century English engineer George Cayley, an early pioneer in modern aeronautics who experimented with propellers and gliders. Some even say this plaything may have been the inspiration for the invention of the helicopter.

Kites

Ancient philosopher Mozi (墨子) is believed to have been the first to experiment with making kites with wood about 2,300 years ago. The pre-Qin (before 221 BCE) book Han Feizi (《韩非子》) recorded that after Mozi’s failure, his pupil Lu Ban (鲁班) replaced the wood with bamboo and managed to make a bird-shaped kite, which could fly for three days.

At first, kites were deployed in war to deliver messages. According to History of the Southern Dynasty (《南史》), an official historic text recording the history of the Southern dynasties from 420 to 589, when Emperor Wu of the Liang State was under siege by rebels, he used a kite to send word for help. But unluckily, the kite was intercepted and the emperor captured.

In the Sui (581 – 618) and Tang (618 – 907) dynasties, as the paper-making industry began to flourish, paper kites gradually became mainstream, with their main function for entertainment. In the Song dynasty (960 – 1279), flying kites around Tomb Sweeping Day to take advantage of the spring wind became a folk custom. People would cut the string once their kite was high in the sky, believing that one’s illness and bad luck would fly away with it.

Nowadays, kites are still a popular plaything among the Chinese public. The whole city of Weifang, Shandong province, thrives on this ancient craft, with a commemorative square, a museum, and a two-billion-yuan industry all centered around kite-making.

Flying bombs

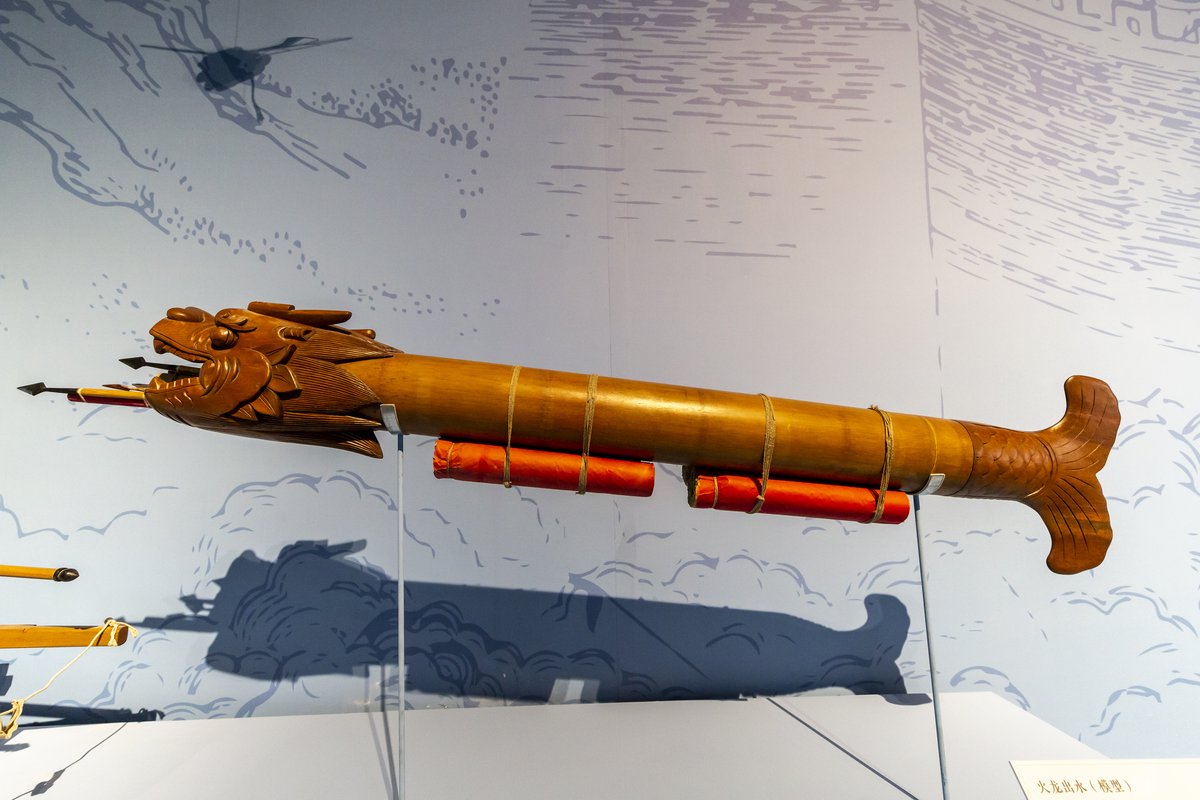

In the Ming dynasty, aerial inventions became more fatal. The “flying crow bomb (神火飞鸦)” was a famous example. According to Records of Armaments and Military Provisions (《武备志》), a book documenting all things military in the Ming dynasty, this weapon is crow-shaped and made of bamboo, straw, and paper. A large amount of gunpowder fills both the bird’s belly and four additional rockets attached to its body. The body comes with a longer fuse than those on the rockets. All ignited at the same time, the rockets would carry the “crow” a great distance, and when it reached the enemy, the longer fuse would burn up, causing the bird to explode.

An upgraded version of the bombing flying crow is called “fire dragon rising from water (火龙出水),” which is more like a two-staged rocket. It generally takes the form of a bamboo tube, about 5 feet long, with a dragon’s head and tail carved on its ends. Four rockets full of gunpowder are attached to the tube to propel the “dragon,” and several more small rockets full of gunpowder are placed inside the dragon’s body. When the four outer rockets are launched, the “dragon” can fly for hundreds of meters, and when they burn out, fuses linking the outer rockets to the inner ones are automatically ignited. The rockets inside then fly out of the “dragon’s” mouth, exploding when they reach the target. Such devices were used on both land and sea

(Almost) Flying humans

Perhaps the sight of all the aerial inventions taking to the sky inspired the idea of sending humans up there too. Sometimes, the experiments were cruel. According to the History of the Northern Dynasties (《北史》), Gao Yang (高洋), a tyrannical emperor of the Northern Qi dynasty (550 – 577), once ordered condemned prisoners to take a kite and jump from a platform tens of meters high, claiming that those who survived would be absolved of their crimes. Predictably, many leaped with a glimmer of hope, only to plunge to their death.

Long before that, some willingly tried to fly. According to the Book of Han (《汉书》), Wang Mang (王莽), a Han official who later overthrew the Western Han (206 BCE – 25 CE) government and founded the Xin dynasty, once recruited people with special talents from around the country to defend it from invaders. Among the people who answered the call was a man who claimed he could fly. When Wang asked the man to prove his talent to the public in the city of Chang’an (present Xi’an of Shaanxi province), the man used some bird feathers to make wings, covered his head and body with more, and twined many belts and ropes around himself.

Despite much anticipation, he only managed to “fly hundreds of steps away before falling down,” states the Book of Han. However, as recent news attests, his epic failure did not stop Chinese people from reaching for the skies in the ages to come.