A film from late 2022 offers something different from the maudlin sentiment of mainstream Chinese films about the human toll of Covid-19

This review may contain spoilers for the film.

At some point, not very far into the future, a review of a Chinese movie about the Covid-19 pandemic might need to start with a lengthier explanation of the epidemiology of the virus, the sociology of city and apartment complex lockdowns, the heroism of nurses, doctors, and food delivery workers, the physiology of a cotton swab up the nostril, and the economics of mask distribution.

These common motifs of life in China over the previous three years have abruptly disappeared as strict pandemic controls have been lifted. It is only a matter of time before they fade from our daily concerns and then from living memory. But what makes ripped-from-the-headlines pandemic movies appealing to audiences at present—whether it is cathartic entertainment, sentimental remembrance, or odes to everyday heroes—will not necessarily be why future generations take them in.

Hero, the latest Chinese film to come out of the pandemic experience, was made and screened at a unique time, with its September 2022 release date putting it on the cusp of great change in local policy. It also comes far enough out from late 2019 for the filmmakers to reflect on the intervening three years, and is the first film that might serve as a considered look back as China emerges on the other side.

Composed of three shorts by female directors that each depicts a snippet of ordinary people grappling with the trivial realities rendered by the pandemic, Hero is the least bombastic and most nuanced of the pandemic films that have been released since 2020. It is a good place to start analyzing the human cost of the previous three years, and how to make art about it.

Hollywood has tackled this topic with harmless romantic comedies (Alone Together, written and directed by Katie Holmes, dramatizes a locked down love affair, for example), or dystopian thrillers (Safer at Home depicts the collapse of the United States as the death toll climbs into the tens of millions).

By comparison, mainstream Chinese filmmakers have generally treated the topic with solemnity and patriotic sentimentality, building from With You, a 20-part TV series released on iQIYI in late 2020, which established a general type for filmic responses to the ongoing events: rather than attempt to depict the overall situation from the top down, the series worked with a range of relatable characters to form a narrative mosaic larded with messages about self-sacrifice. Answering the Call, a film released in 2020, builds on this model, focusing on unassuming figures who must work together to save the locked down city of Wuhan, with heartrending scenes of family separation and altruistic sacrifice. Andrew Lau’s Chinese Doctors, released in 2021, is equally pure in its emotional appeals, depicting the Herculean efforts of the people of Wuhan in their fight against Covid-19.

Hero does not, like these Hollywood pictures, take the pandemic situation only as a backdrop, nor does it attempt, like these Chinese features made while strict measures against the virus were still being enforced, go for a heroic narrative, celebrating personal sacrifice for the greater good.

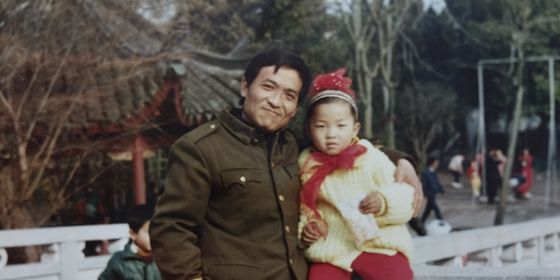

The film’s three segments are connected by time, if not place. They visit Wuhan, Beijing, and Hong Kong in the first two months of 2020. Joan Chen, the famed actress-turned-director who has made a few films focusing on female characters, takes on the first story: Shen Yue (Zhou Xun) and her mother-in-law (Xu Di) must come to grips with their own complicated relationship, while also fighting the rising panic and terrifying symptoms of a disease that they understand little about.

The second segment, directed by Li Shaohong whose lengthy resume includes films ranging from the 1988 cult thriller The Silver Snake Murders to numerous palace intrigue dramas for television, shifts the setting: a girl named Zhou Xiaolu (played by Huang Miyi, a dead ringer for a young Zhou Xun, coincidentally) has just returned to Beijing from Wuhan, where she was engaging in a chaste romance with Li Zhaohua (Jackson Yee). The two communicate in video chats, which are the only images seen in color in the monochrome segment. When she learns that her lover is struggling with a high fever and a lingering shortness of breath, Zhou Xiaolu schemes to head back to Wuhan to be with him. But her mother discreetly alerts the residents’ committee, who order her to remain in the city for the next 14 days. Li Zhaohua dies in the hospital, clutching his phone; his final moments are streamed to Zhou, crisp and clear.

Sylvia Chang, also a household-name director and actress with many awards under her belt, sets the final segment in Hong Kong in February of 2020. Against the backdrop of panic buying and paranoia, Sammi Cheng plays a photographer whose marriage to another photographer is disintegrating. With her husband constantly rushing around the city, she is forced to shoulder the burden of looking after their two children, while also completing her own assignments. An eventual reconciliation between the couple gives the film its first happy ending.

Hero complicates the sentimentality that is delivered straightforwardly in a picture like Answering the Call. In Chen’s segment about a woman and her mother-in-law quarantining together, what might have been played as a tale of filial sacrifice turns out to be a realistic portrayal of the emotional and physical toll of the pandemic. Shen Yue is trapped, depressed, and seems constantly on the verge of coming apart; and her mother-in-law, spritzing disinfectant on every surface and accusing her daughter-in-law of uncleanliness, embodies the fear and hysteria of the period. When Shen Yue must finally tell her husband that his mother has passed, the sentimental appeal is subverted by the fact that it’s Shen Yue— gasping for air, trying to protect her family, all while battling the old woman—whom we root for.

A similar complication is introduced in Chang’s segment, with a subplot about the photographers’ Filipina maid: all of the melodrama between the couple seems petty compared to the suffering of their hired help, who is forced to talk to her own children by video chat, unsure when she will see them again. Whenever the viewer risks being swept away by Sammi Cheng’s battles with her detached and emotionally unavailable husband, director Chang returns us to a scene of the overwhelmed housekeeper weeping for her children, or being harassed by her employers’ elderly relatives.

These shades of gray are tolerable in a film made outside the frantic first couple years, when injections of good feeling are not quite as necessary, and it seems to be time to take a look backwards. This is true for Chang’s segment as well, which attempts through the photographer characters a more nuanced excavation of social realities. The viewer tags along with the photojournalists as they snap pictures of hidden suffering in Hong Kong under lockdown, yet their subjects—people struggling to make ends meet after being laid off, desperate parents lined up to buy essentials for their children—are presented here in a flat, journalistic way, which does not allow the subjects to be inflated as models of self-sacrifice. Compared to the relative privilege of the photographers, who, at least as long as the pandemic continues, don’t face any risk of losing their jobs, the suffering of the Hong Kong middle- and working-class comes into sharper focus.

The timing of Hero’s production allows it to move past the narrow focus on emergency pandemic response. Even though all of the segments are set in the first two months of 2020, each one suggests or depicts some aftermath. These conclusions are bittersweet in the first and third segment, with Shen Yue reuniting with her husband and son after the death of her mother-in-law and a brush with shortness of breath. Life goes on for the photographers, too, who also eventually get back together.

They take on a more haunting aspect in Li Shaohong’s segment, in which the viewer is taken along on Zhou Xiaolu’s return to Wuhan, where she conducts a mourning ritual—cutting her hair short, putting on her boyfriend’s clothes, and drifting around his apartment like a phantom.

Hero breaks from earlier films, like Answering the Call and Chinese Doctors, whose emotional resonances were restricted to strains of positive empathetic emotion. The mobilization of gandong (感动)—a word that means to be moved, emotionally—in these films was similar to that in other heroic official narratives. Chenchen Zhang, a scholar of international relations at Durham University, describes gandong in a 2022 paper as a phenomenon in which “one is (encouraged to be) moved, in a positive manner, by the bravery of the heroes, the unity of the people, and the strength and resilience of the nation facing unprecedented challenges.”

This is a “spontaneous response,” Zhang notes, but also a function of what is termed affective governance, or the definition and recognition by governments of emotional relationships between citizens. The story of heroic physician Yang Xiaoyang (Jackson Yee) in Chinese Doctors, who must face this medical emergency, inspires warm feelings, but also makes a statement with this emotional resonance about the response of the country itself. The self-sacrifice of everyday citizen volunteers and medical professionals in Wuhan in With You is a jolt of positive emotion, a psychological B12 shot to propel the viewer to their own feats of self-sacrifice; and also, through this an invitation to feel the same emotion toward fellow citizens and the nation itself.

This is not to say that Hero is superior because it avoids easy emotion and a narrow look at the early days of the emergency, but it suggests that it is a different kind of film, closer to an autopsy than an emergency resuscitation. As valuable as the earlier films were to their moment, Hero says important things about the reality of life in the aftermath of the pandemic. Whether there is a market for unvarnished portraits of the period among those who lived through it is another question.

Can ‘Hero’ Save the Pandemic Film Genre in China? is a story from our issue, “Kinder Cities.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.