As “outsider art” gains attention in international exhibitions, artists and art-lovers without formal training from China see new opportunities for self-expression

Feng Cangyu wanted to become an insider. In 2007, the self-taught artist (and former farmer, steelworker, clothes-seller, and small-time antiques trader), then 43 years old, felt pretty good about the experimental ink landscapes he had been tinkering with for three years, so he marched down to Beijing to knock on some gallery doors.

“They asked me, ‘What association are you part of?’ I said, ‘None,’” Feng recalls on a video call with TWOC, “and they said, ‘Then we don’t want to look at [your work].’”

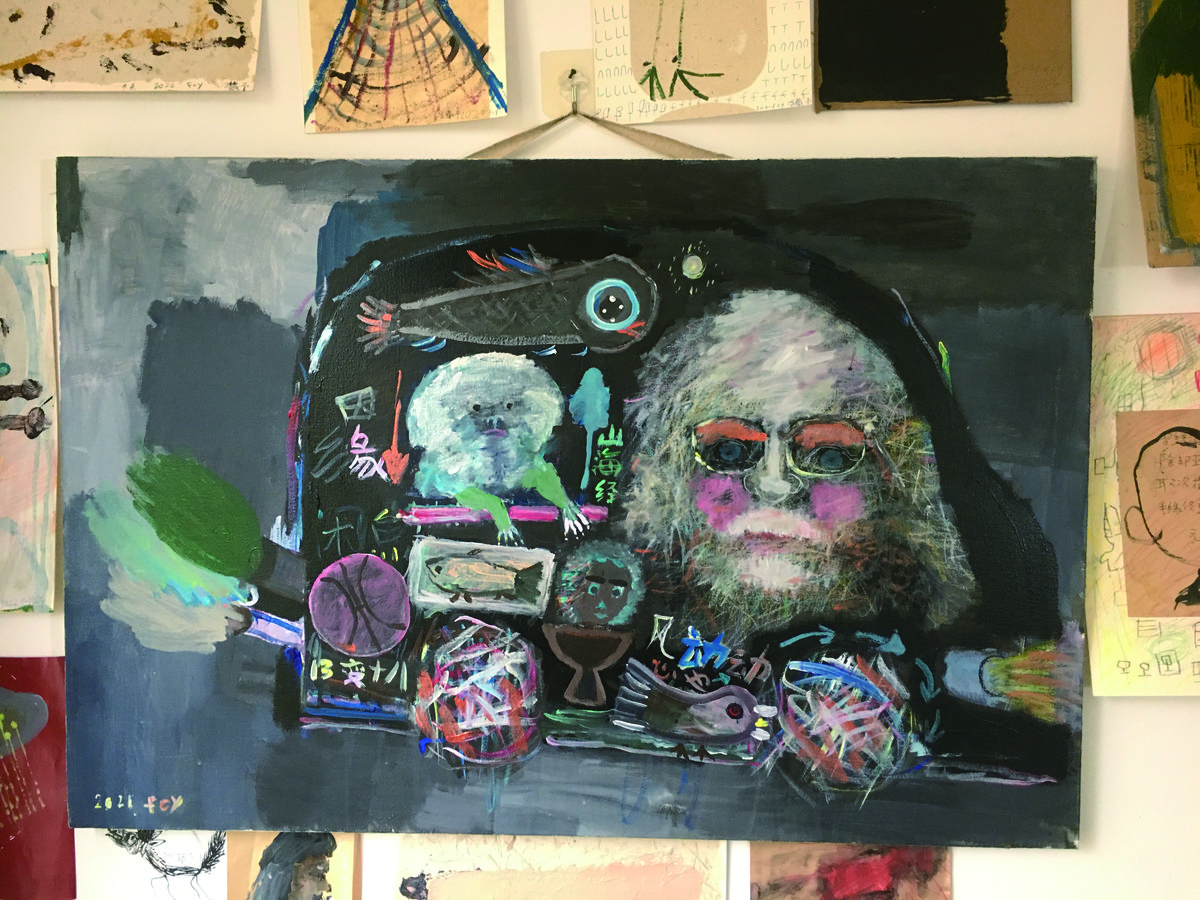

A decade later in 2017, Feng, who is from Fushun, Liaoning province, found himself invited to the 7th Biennale Hors Normes in Lyon, France, to present his works—which have grown increasingly wild, often featuring ghostly acrylic animals and human figures held together by prickly lines, and made on found scrap paper or fabrics. He was also asked to paint a mural for the event. But this wasn’t intended to make Feng an art world insider, either, as the biennale is a fair dedicated to “outsider art.”

Outsider art is commonly understood as “work by artists who have not had any formal training, and who have never been part of the art establishment,” writes Cara Zimmerman, head of outsider art at Christie’s, in an article published on the company’s website. “Some of those described as outsiders have come from difficult circumstances, having experienced poverty or mental illness.”

But this category has been slowly making its way “inside”: The fact that there’s a department and specialists devoted to it at Christie’s, one of the world’s leading auction houses, is perhaps proof that the art world is developing systems for exhibiting, collecting, and studying this type of art.

In between Feng’s train ride to Beijing and his flight to France—his first time on a plane—came a decade that saw considerable action in the field of outsider art in China. Galleries, exhibitions, and studios championing outsider art emerged to bring more than 100 artists to public attention, some even internationally.

In the West, the concept of outsider art has existed since the 1940s when French artist Jean Dubuffet first came up with the term art brut to demarcate coarse, generative artistic expressions from outside the confines of “fine art.” Advocates of outsider art appreciate its “raw, democratic origins,” writes Zimmerman.

But by marking off an “outside,” the category ironically created an opportunity to challenge the boundaries of what constitutes worthy art. In January 2022, Christie’s sold American artist William Edmondson’s chubby 1936 sculpture “Boxer” for 785,000 US dollars, setting a new record price for outsider art.

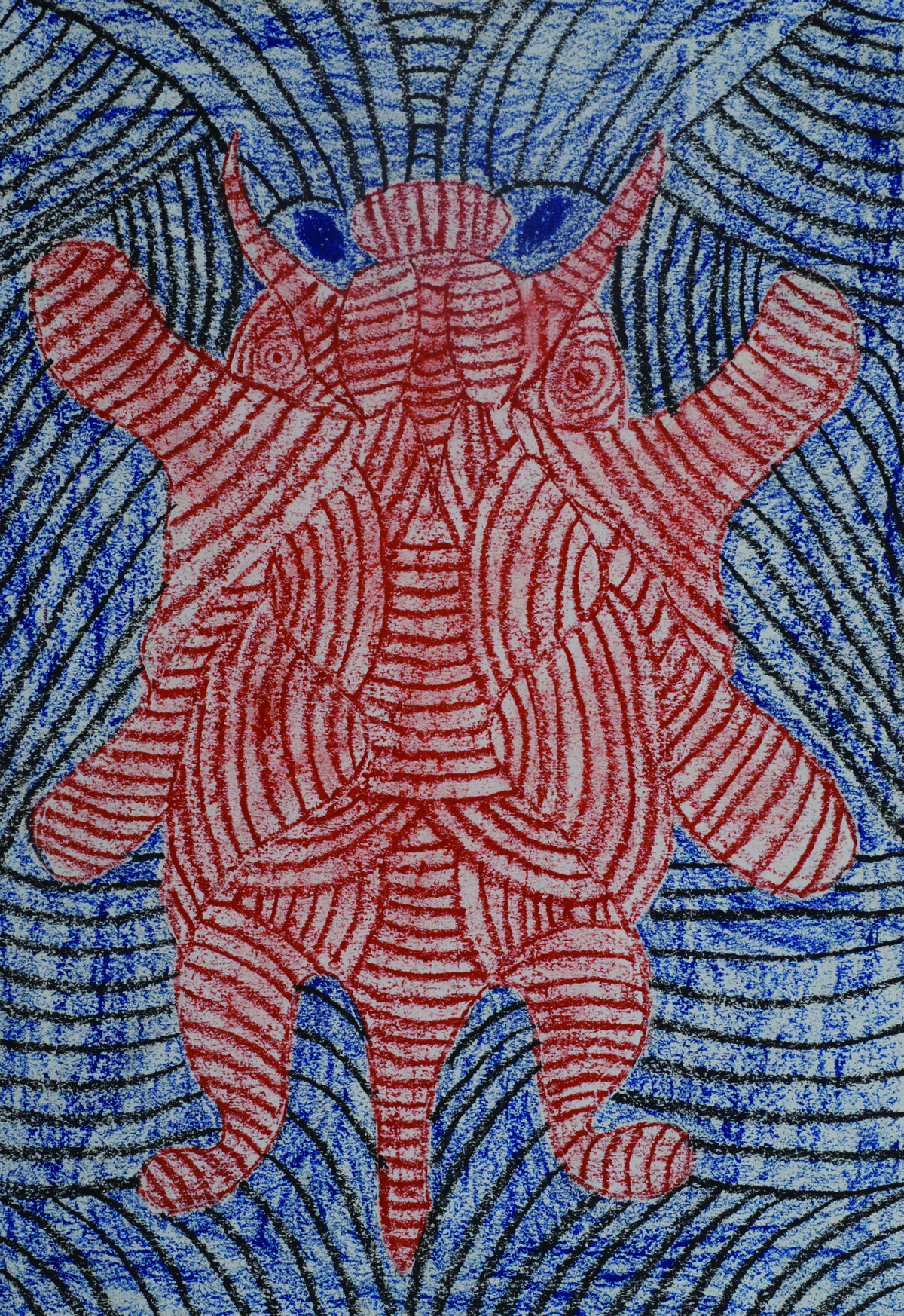

In China, Guo Fengyi, often considered the first outsider artist to be recognized on the mainland, was not “discovered” by Long March Space gallery until 2002. Born in 1942 in Xi’an, Guo started to paint the fantastical visions she was experiencing in her late 40s after qigong practice. Mythical creatures made of fine lines flew from her brush: two goddesses joined by a shared torso that looks like a colorful cloud, a skeletal body formed by blue and red arrows, imaginative figures that are both mythical and fearsome at the same time. Some of the creations are up to five meters in length.

One day in the fall of 2015, Feng arrived at an “outsider art lecture” in Beijing’s 798 Art district—“two foreigners debating on stage and a pretty translator,” as he remembers the event now. He’d heard about the talk through the grapevine, and came with an old iPad loaded with some unruly acrylic works from his early days: a grumpy cow that looks like it’s melting into the darkness; a red-faced person emerging from a cloud of dark blue with an eerie smile and a piece of watermelon. These successfully captured the attention of the panelists when he went up to them after the event.

The interpreter at the event, who expressed particular interest in Feng’s work, was Sammi Liu, the mastermind behind the Almost Art Project, an annual Beijing exhibition dedicated to introducing outsider artists (which held five editions before it was interrupted by the pandemic in 2020). Before AAP’s inaugural event in 2015, Liu’s gallery Tabula Rasa had initiated a society-wide search for artists who were not professionals and didn’t have a background in formal art education, but loved creating art nonetheless.

In addition to Feng Cangyu, this brought them to the likes of Wang Hua, a dining hall worker at the Central Academy of Fine Arts, who finds solace in her basement apartment every day after work by covering long white scrolls with thin, delicate black lines; and migrant worker Li Zhongdong, who picks up abandoned wood boards and magazines and creates drawings and collages with an almost religious mystique.

To Liu, these works and backstories were a refreshing departure from an industry too often driven by fame and profit. “Whether the works sell, or if they can sustain a living with art—these issues that trouble most [professional] artists do not exist for these people,” she told news outlet Yicai in 2015. “They just never spend a day without wanting to create art.”

Feng certainly seems to inhabit this role. “I get up at 5 every morning, and I fool around until 11 almost every night,” he says. “Sometimes I don’t really know what I’m doing, but I never have a moment of down time.” He turns his phone camera around and shows TWOC an apartment full of paintings—racked up on shelves, doodled or carelessly taped up on walls, or still drying on the easel.

When asked what drove him to art, Feng frowns and scratches his head. “Ah, I don’t know,” he says, adding that every time he’s about to pick up a paintbrush, he finds his mind is a blank slate, “It’s like those aunties dancing in the park: it comes as soon as the music is on.”

But while the persona of a pure-hearted artist might make for a good selling point, it hasn’t raked in much profit for Feng. In 2021, years after that first bold self-introduction at 798, Feng moved from a courtyard in Beisizhuang village in Songzhuang, commonly considered Beijing’s last affordable outpost of artist communes, to Yanjiao town, Hebei province. This satellite city attracted many Beijing commuters, and now artists, with significantly cheaper rent.

Perhaps Feng could have kept his Songzhuang courtyard had he accepted the offer from a collector that year. “He wanted to pay me 20,000 yuan every year…for 10 paintings each year for five years, and see if they appreciate.” He rejected the offer, saying, “Having to produce a certain amount of painting for someone would be so tiring. And not fun.”

Today, Feng only sells a few paintings every now and then when he needs the money. They go for as little as hundreds or as much as 2,000 yuan, and are often bought up by artist friends, or go through them to reach other dealers.

From the lines of eccentric clay figures featuring rough complexions or hollow eyes drying by his window, he picks out an approachable teacup—brown, covered in thumb-sized dents, no frills—and flaunts it in front of the camera. Someone he knows recently helped him sell a few dozen for 200 yuan each on Douyin. “They also tried to sell a few of my paintings, but no one wanted them.” He is surprised to learn from TWOC two paintings he had sent for a collaboration with Tabula Rasa has been listed by Line Years, an NFT art trading platform, for 7,500 Hong Kong dollars each.

While “having fun” bubbles up a lot when Feng describes his relationship with art, this is a luxury not affordable to all outsider artists. “Many artists, when they first start working with us, are very protective of where they sit, their desks, tools, and paper. They allow no one to touch them,” Guo Haiping (no relation to Guo Fengyi), an artist and advocate of outsider art, says of the artists he works with, who are often struggling with mental conditions such as bipolar disorder and schizophrenia or intellectual disabilities.

“In China, these people have had limited space to live. Their thoughts and behaviors are often invalidated,” he says. “But now they finally have a desk to draw on, a space to call their own, they treat their art as their life…and they defend this space like their life.” Guo has been encouraging patients in psychiatric hospitals to paint and draw since 2006, and in 2010, he established Nanjing Outsider Art Studio, a space for patients to safely express themselves without judgment or restrictions and the first of its kind in China.

Since 2013, the studio has been holding exhibitions for outsider art (another first in China), and helps the artists here to exhibit at the Almost Art Project each year. Guo proudly shares the works fresh out of the studio daily on his WeChat social feed.

One of Nanjing Outsider Art Studio’s most recent exhibitions, held on October 10, was backed by the local chapter of the Disabled Persons’ Federation. Of the almost 50 paintings exhibited, all were sold on the opening day to Nanjing’s Yao Museum (run by a friend of Guo’s). “The Federation asked us to sell more works or merchandise…to marketize, to become self-sustaining,” Guo tells TWOC, yet says that he fears selling works would compromise the integrity of the art. He hopes to eventually open a public-facing museum.

Arts education and people’s aesthetic preferences in China today, Guo contends, “are so out of touch with each individual’s life…[The artworks] have to either look like something, or look like some master’s work. Without these reference systems, [people] lose their ability to judge a work’s value.”

When Guo Fengyi’s gods and demons were selected for the Venice Biennale in 2013, Chinese art critic Peng De published a strongly worded critique, calling it a “mockery” of Chinese contemporary art. “If Guo Fengyi’s images represent China, it means China’s art world has no thoughts, no culture, no contemporariness,” he wrote, likening Guo’s paintings to a child’s doodles.

Guo Haiping, on the other hand, sees Guo Fengyi’s work as a free expression of her own lived experience, which “is exactly what Chinese professors and students ubiquitously lack,” he wrote in a 2013 rebuttal to Peng’s critique. “The most important thing is that her works indeed incited attention, controversy, and introspection in China’s art world.”

In Guo Haiping’s experience, most people, in and out of China, are unable to appreciate outsider art independent of the artist’s unconventional backgrounds. Tabula Rasa’s Liu has also expressed her concern about the “outsider” label. “It might risk exploiting marginalized groups,” she says.

In the first Almost Art Project exhibition in 2015, Liu tried to guide the audience to directly face the works themselves without giving them information on the artists’ background until the very end. But as it turned out, visitors were keen to find out more about the human story behind the works.

Guo Haiping believes that the insistence on judging a piece of art by its form only, without considering the artist’s background, falls exactly into the “rigid value system” that alienates art from human experiences. The emotions outsider art evokes—be it curiosity, compassion, admiration, or something else—actually “make us more attentive to the lives behind the art…and brings back the vitality in art,” he says.

He believes that many learning journeys start from a desire for something unique—“many begin their appreciation for Van Gogh from a point of novelty”—and that the problem does not lie in society’s “othering” of outsider artists, but its treatment of anyone who is different. “Every life is born different…We should learn to appreciate and cherish the different, the eccentric,” he adds, “This is where Chinese people need to change their mindset…And outsider art is giving us an opportunity to discover and adjust our own shortcomings.”

Feng has come to accept, even relish, his status as an outsider. “It’s so normal that people don’t accept things they don’t know,” he says. He rejected advice from an artist friend to make his painting “prettier,” saying, “I know what I’m painting…if I have to paint anything prettier, I’d feel uncomfortable all over.” He muses that, “If art is a mountain, I think reaching for the summit would make it lose its charm.”

Recently he became inspired by the rocks in the river near his home, which he has piled up into a knee-high mountain in a corner of his room. “Not sure what I’ll do with them yet; I just bring them back for now,” he says, holding a pebble up to the camera, his eyes gleaming as if he’s found the treasure of a lifetime.

Outside Looking In is a story from our issue, “Promised Land.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.