The Lunar New Year and Lantern Festival are key scenes of drama in China’s Four Classic Novels, providing clues of how people celebrated holidays in ancient China

Being the most prominent celebrations in China, the Lunar New Year and the Lantern Festival provide great settings for high drama in much of Chinese fiction.

So it’s no surprise that all of the Four Classic Chinese Novels, that is Romance of the Three Kingdoms (《三国演义》), Outlaws of the Marsh (《水浒传》), Journey to the West (《西游记》), and Dream of the Red Chamber (《红楼梦》), written between the 14th and 18th century, feature these holidays in their storytelling. But it is not always a joyful time for the characters.

Believed to have been authored by Luo Guanzhong (罗贯中) in the late 14th century, Romance of the Three Kingdoms is the ultimate novel of cunning politics and military strategies. It is a dramatization of real events when warlords contended for power at the expense of the dying Eastern Han dynasty (25 – 220). The scheming and plotting never stop, even during the holidays.

On one particular Lunar New Year described in Chapter 54, warlord Liu Bei (刘备) strives to escape the honey trap set up by warlord Sun Quan (孙权): Sun lures Liu to his home by promising Liu his younger sister’s hand in marriage, and plans to keep Liu there. But Liu manages to convince his new wife to flee with him. On New Year’s Day, the couple visits Sun’s mother and asks to get out of the city to worship Liu’s ancestors. While Sun is getting drunk holding celebrations and banquets with his officials and generals, the couple gets away for good.

Warlord Cao Cao’s (曹操) holiday season was even more eventful, as he put down a rebellion. One Lantern Festival evening, a group of rebels sets fire to the capital city, hoping to get the emperor out of Cao’s control while he’s away. Chapter 69 of the novel paints a picture of a peaceful holiday before the disaster: “That night, the sky was clear, and the moon and stars shone brightly. All streets and markets were lit by colorful lanterns. The night curfew was lifted.” Unfortunately, the rebellion is crushed and Cao has hundreds killed as punishment.

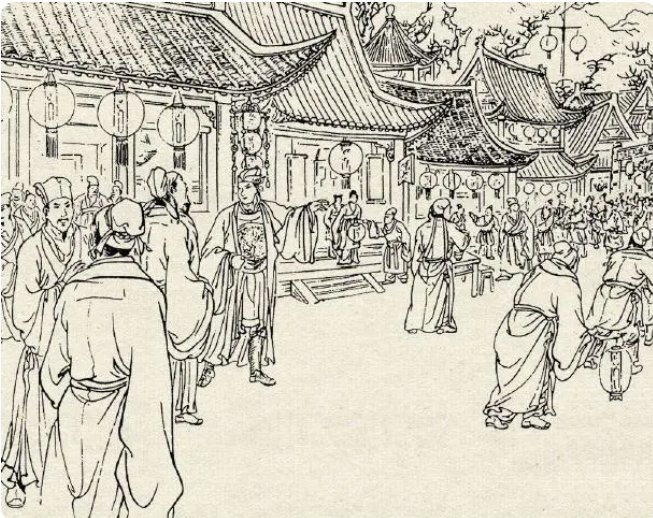

These were not the only rebels who saw an opportunity during the Lantern Festival, which was traditionally the only time in ancient China when shops would stay open and civilians could roam freely on the streets after nightfall. In Outlaws of the Marsh, attributed to Shi Nai’an (施耐庵) in the mid-14th century, the band of outlaws draws up a plan to rescue their imprisoned brothers in the city of Daming Fu during the night of the Lantern Festival, also by setting a fire as a diversion.

The novel describes the festivities at the time of the Nothern Song dynasty (960 – 1127) in great detail. Much like the modern-day Christmas decorations, rich families in Daming Fu put up tents at their gates to showcase exquisite lanterns and set off rare fireworks to attract passersby. In front of the city administrative office, a turtle-shaped hill consisting of thousands of lanterns, called aoshan (鳌山), was erected. Two dragon lanterns, one red and one yellow, coiled over the hill, with each dragon scale featuring a small light while clean water gushed out of their mouths. Celebratory street performances called shehuo (社火), ranging from operas, acrobatics, to comedy shows, could be found everywhere.

The unfortunate location the outlaws choose to set their fire in Chapter 66 is the biggest restaurant in the city, the Cuiyun Tower. With three floors and up to a hundred rooms, the building is typically filled with music, drum beats, and clattering crowds all night long, making it the perfect spot for even more chaos.

Later in the book, Chapter 72, the author depicts a grander Lantern Festival in the capital city, Dongjing (present-day Kaifeng, Henan province) with more lights, entertainment, and exuberance. This time, the band leader, Song Jiang (宋江), sneaks into the city hoping to meet the emperor in secrecy through his courtesan. That night, the emperor leaves the palace to celebrate with his subjects, or 与民同乐, a Confucian virtue of benevolent rulers. He makes a stop at his courtesan’s home, waiting for his son, the prince, to finish bestowing imperial wine to the city residents, and for his brother who was hosting a charity market called maishi (买市) —both common activities of royalty and aristocrats during festivals at the time. Song is almost successful in hiding in the courtesan’s house, until Li Kui (李逵), his hotheaded band brother, starts a fight with the emperor’s officer. The band ends up fleeing the capital.

The next Lunar New Year comes up in Chapter 110 after Song Jiang and his band received amnesty from the court, and he himself became a low-ranking official. He waits outside the imperial hall from dawn to noon without a glimpse of the emperor, though he finally gets a taste of the imperial wine shared among the officials who gather to celebrate—no doubt a very disappointing New Year for Song.

The Lantern Festival depicted in the Journey to the West, attributed to Wu Chengen (吴承恩) in the late 16th century, perhaps best reflects the holiday’s Buddhist origin. Partially started as a worship ritual of offering lights to the Buddha in the Eastern Han dynasty, the Lantern Festival remains an important celebration in temples and monasteries today. In the story, the Tang Monk (唐僧) and his disciples stay at Ciyun Monastery in Jinping Fu, a city of the Tianzhu Kingdom (present-day India) during the Lantern Festival. In depicting the festival, the author includes exotic elements, such as lanterns shaped like black lions and white elephants, while the city’s residents ride through the streets on the backs of elephants.

While touring the city, the group of traveling monks discovers a costly local tradition: offering three giant lamps to Buddhas, each filled with 250 kilograms of fragrant vegetable oil. Three bodhisattvas would grace the Gold Lamp Bridge to receive the lamps, which would then burn out overnight. Ever so gullible, the Tang Monk insists on paying respect to the bodhisattvas when they arrive. But of course, he is kidnapped by these fake bodhisattvas, who are really oil-thirsty rhino monsters in disguise.

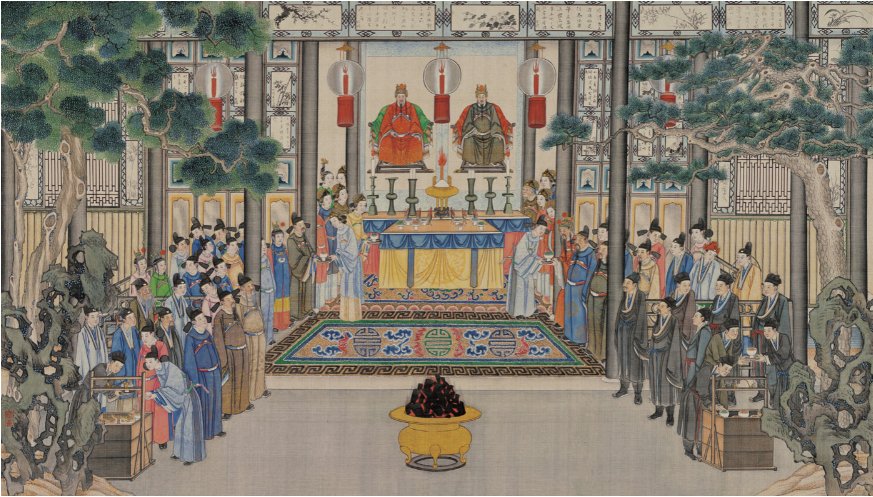

A novel known for depicting domestic life, Dream of the Red Chamber, written by Cao Xueqin (曹雪芹) in the mid-18th century, offers the most detailed accounts of the Lunar New Year and Lantern Festival in the homes of aristocrats. The Lunar New Year preparations in the Jia clan start during Layue (腊月), the last month in the lunar calendar, when the ancestral temple is swept, various ceremonial ware is laid out, and guest lists are drafted. Young mistresses of the house are also in charge of preparing gifts for relatives and servants, such as gold and silver ingots, today’s equivalent of yasuiqian (压岁钱) in red envelopes. Young masters receive holiday gifts from the emperor on behalf of the family, which consist of certain numbers of silver coins held in yellow bags.

A famous scene that provides insight into the livelihood of the aristocrats and common people in the mid-Qing dynasty (1616 – 1911) unfolds in Chapter 53 between master Jia Zhen (贾珍) and his farm manager, who comes delivering New Year gifts as well as the proceeds from the farm. Readers are presented with a gift list that goes on for an entire paragraph, consisting of game meat, livestock meat, seafood, nuts and resins, charcoal, rice, grain, and various dried vegetables. On top of these supplies are 125 kilograms of silver (by some estimation, worth about 550,000 yuan today). Readers then learn that Jia Zhen is not happy with the sumptuous offerings, accusing the manager of coming up short—clearly, the lavish lives of aristocrats were beyond the imagination of most ordinary people.

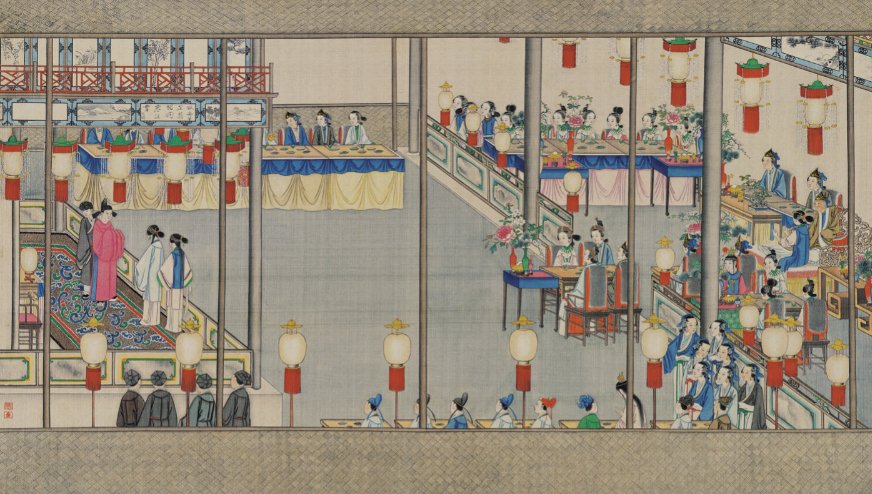

On the Lunar New Year’s Eve, the family hangs new couplets or duilian (对联) and pictures of the Door God, or menshen (门神), while lighting red candles in the main hall. The next morning, clan members with official titles enter the court to visit the emperor and attend the royal banquet. At home, all male clan members gather for a sacrificial ritual in the ancestral hall, while inside the mansion, Grandmother Jia, the matriarch, leads another ritual to worship the portraits of the founding brothers of the Jia clan, Duke Rongguo and Duke Ningguo. Given that female members were not traditionally involved in ancestral worship in Han culture, this depiction is a unique reflection of the Manchu culture of the Qing dynasty (1616 – 1911) when the novel was written.

The author meticulously depicts the luxury enjoyed by the Jia family, from the tasteful incense, potted plants of fresh flowers, to porcelain tea sets and embroidered ornaments, let alone all kinds of crafted lanterns. Opera, instrumental music, storytelling, jokes, dishes and snacks, wine and fireworks, the festivities fill two whole chapters. Interestingly, nowhere to be found in these depictions are jiaozi, or dumplings, possibly because the Jia family (and the author Cao Xueqin’s family) are from the South, while eating jiaozi during festivals is a northern tradition. In all of these classic novels, festivals are interesting gatherings offering much drama and plot-development. Even the seemingly cheerful celebrations in the Jia family forecast their eventual doom through greed and corruption.