These scenes of pre-New Year celebrations in southern China will put you in the mood for the holiday

In China, the Lunar New Year starts small. On either the 23rd or 24th of the last lunar month (with the date differing between the North and South of China), a festival called the “Little New Year (小年, Xiaonian)” provides a dress rehearsal for the big celebrations taking place approximately one week later: a chance for people to clean their homes, finish their shopping, and start getting in the festive spirit.

Besides the Lunar New Year’s Eve (除夕, Chuxi), New Year’s Day (正月初一, Zhengyue Chuyi), and the seven-day national holiday that sees millions of people traveling to their hometowns, the Lunar New Year season traditionally lasted almost a month from Xiaonian to the Yuanxiao (Lantern) Festival on the 15th day of the first lunar month, or even the 19th day (called Yanjiu Festival) in some parts. There are different rituals meant to take place each day, such as worshiping the “God of Wealth” and burning offerings to one’s ancestors. In these busy modern times, most of these observances have fallen out of fashion, but the southeast of China—including Fujian province and the Lingnan and Chaoshan regions of Guangdong—has always been a stronghold for traditions, and its New Year celebrations are no exception.

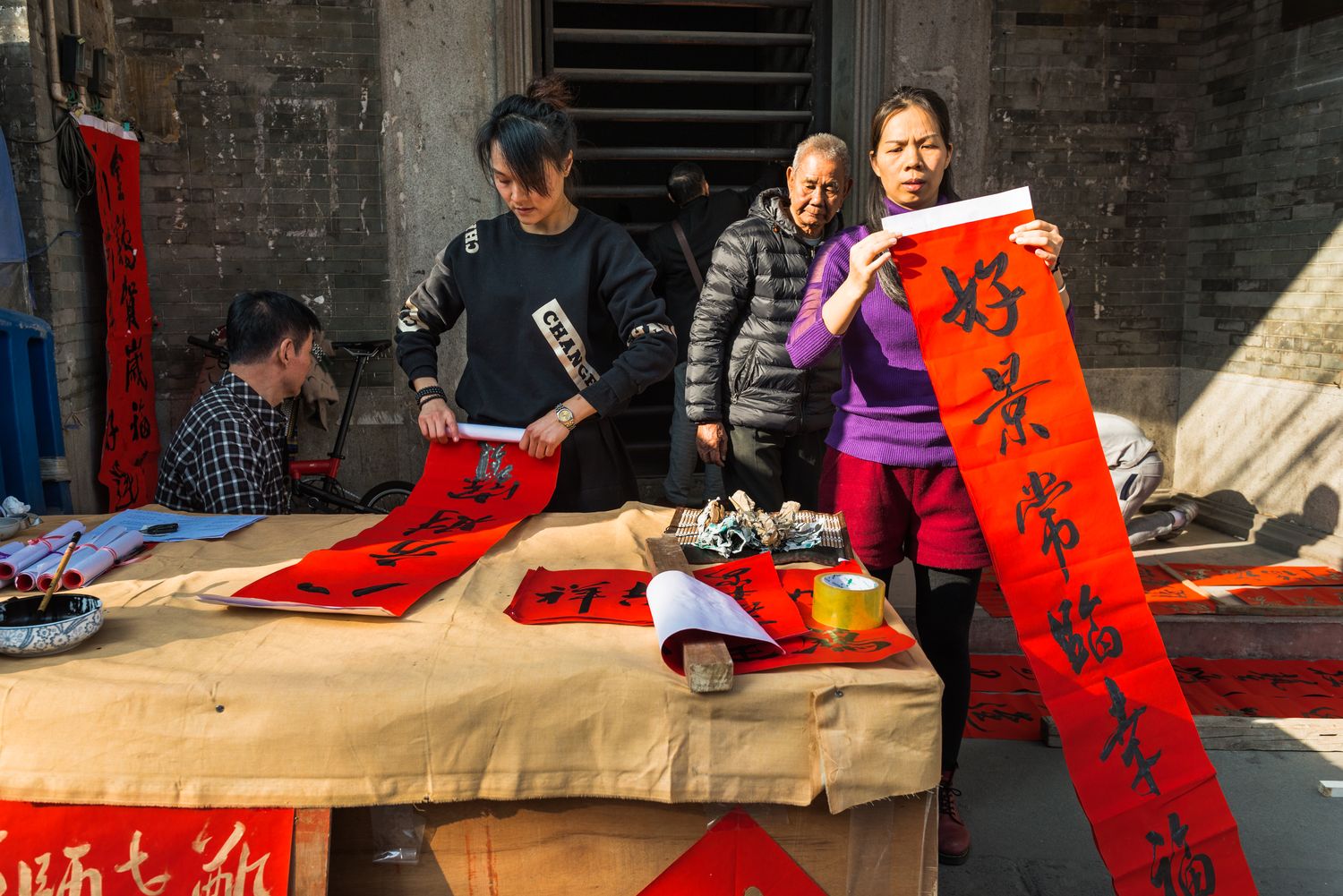

Huang Ruide, a photographer based in Guangdong with a strong interest in folk culture, has spent years documenting how people in his province get in the mood for the holidays. His first series, “A Sea of Red Welcomes Spring in Foshan,” takes place on Kuaizi Road, a street in Foshan, Guangdong, lined with dozens of stalls where calligraphers handwrite auspicious mottoes and “couplets” to customers’ order. “Rejecting printed material and persevering in the act of handwriting couplets are a part of Foshan’s traditions,” says Huang, who notes that the city also preserves traditions like lion dances, martial arts, dragon boat racing, and bonfires during the Lunar New Year and other traditional festivals.

In recent years, the street has also attracted increasing numbers of young tourists who’ve learned about the unique custom online, and want to experience the New Year amid a “sea” of red paper. Huang observes, though, that the historic “shophouses” lining Kuaizi Road, built in 1935, have fallen into disrepair and are at risk for demolition. “Over a period of eight years, I’ve visited the street three times, but my photos will perhaps become historical records one day,” he muses. “Where will Foshan residents go to buy words then?”

Another series, “Cantonese New Year Atmosphere on Pressed Noodle Road,” captures the bustling roadside stalls of Zhafen (“Pressed Rice Noodle”) Road in Guangzhou, a thoroughfare well-known for its rice noodle shops during the Qing dynasty (1616 – 1911). These days, it’s lined with vendors selling ordinary items like candies, decorations, and mouthwatering snacks served on the spot, but also regional specialties like flowers, Chinese medicine, and potted mandarin orange plants, as 桔 (gat) is pronounced the same as “auspicious (吉)” in Cantonese, and the characters look similar too.

According to Huang, who lives in Guangzhou, flowers and food are essence of New Year celebrations in his city. The capital of Guangdong province is also known as the “Flower City,” with its residents renowned for their horticultural skills since the Han dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE), and visiting the markets to buy flowers is a Lunar New Year tradition. As for eating, Huang believes the pictures speak for themselves: “No more chitchat,” he tells TWOC. “Let’s hit the streets!”

Photography by Huang Ruide (黄瑞德)