Amateur conservationist Yang Fan has explored thousands of little-known historic sites in China, while trying to raise awareness for the need to protect these treasures before they disappear

“We’re here,” Yang Fan says as he parks his car next to the road. “Here” is the middle of nowhere in a bamboo grove up in the mountains of southeastern Sichuan province. The road ahead is occupied by a flock of geese.

A small path by the side of the road paved with crude stone slabs leads deeper into the lush bamboo thicket. It’s been raining for a few days and the cool, crisp smell of wet leaves is in the air, but Yang has no time to soak up the atmosphere. He rushes through a moss-covered stone gate and past a small waterfall. There are no signs, no hints of what lies ahead until Yang reaches a small shrine with smoking incense at the end of the path, signaling that he is approaching his destination: a 50-meter long crescent-shaped rock wall with 222 Buddhist statues and figurines from the Ming dynasty (1368 – 1644) intricately carved into the red stone.

Yang, who calls himself an “amateur relics conservationist,” has been seeking out treasures like this for the past two decades: hidden places and traces of China’s past that he believes are more and more difficult to find. “You can see the rapid development of China over the years, the whole country seems to be changing its face, and many historical sites are disappearing too quickly,” he says.

Yang takes out his phone and starts taking pictures and videos of the rock wall, known locally as the Qingliang Cave, which is adorned with detailed Buddhist carvings, the largest measuring 1.5 meters in height. Painted bright cobalt, rust, and yellow, they stare stoically into the valley.

Beside the carvings sits a small wooden hut with two dogs, a couple of ducks and chickens, and the rooster whose cries we’d heard from far away. This is the home of the caretaker, who seems happy that someone made it all the way up here. In 1997, he explains, his father Liu Chaoyong came up the mountain, built the hut, and started living here to keep the historical site in shape. After his death in 2019, the son took over as new caretaker.

In pre-modern times, historical sites like temples and tombs were believed to be a connection to an area’s ancestral past and were therefore cared for by locals, generation after generation, archaeologists Zhao Huijun and Luc Doyon from the Institute of Cultural Heritage at Shandong University wrote in a paper from 2021. It was only at the beginning of the 20th century that foreign excavation methods were introduced and a collective awareness of the cultural value of these sites and objects, many of which were literally found in people’s homes and backyards, began to take shape.

During the destructive decade of the Cultural Revolution, many such sites were heavily damaged by overzealous Red Guards trying to do away with traditional Chinese culture, among them the carved rock wall in southeastern Sichuan. Caretaker Liu tells Yang how some of the stone relics on site were broken up into pieces and thrown into the valley. It was his father Liu Chaoyong who later moved them back up the mountain and restored them to their original state as much as possible, he explains.

After the reform period began, China passed the Cultural Relics Protection Law in 1982, creating a tiered system by which historical sites and objects receive protection. Since 2013, the Qingliang Cave in Sichuan has been registered at the highest tier—guobao or national treasure, protected directly by the state for its extraordinary historic, cultural, and scientific value.

However, the law lacks clear definitions of what exactly constitutes historic, cultural, or scientific value, resulting in a rather elusive system of decentralized protection at different levels of government, legal scholar Huo Zhengxin from the China University of Political Science and Law explains in a paper from 2015. Besides the highest tier protected directly by the central government, cultural sites can also be registered at the provincial, city, and county level, meaning that local governments are responsible for their protection.

These lower levels of government, however, often lack financial resources and instead prioritize economic development and GDP growth. “Within such a setting, it is natural that local governments generally show special leniency when enterprises damage, or even destroy cultural heritage to make way for commercial construction,” Huo writes. In fact, statistics from the latest national archaeological survey show that by the end of 2011, more than 40,000 historical sites across the country had vanished. More than half of them were destroyed by commercial construction work, with many more now threatened by extreme weather.

The speed of this destruction is unparalleled, Yang believes. “That’s why I always have this sense of urgency when I’m on the road, because the fact of the matter is, if you don’t go visit a place now, next time it might be different already.” His mission to see and document as much as possible has led him to thousands of sites, many of which are unregistered and not under any formal protection.

He often stumbles upon such sites by asking locals for historical relics and sites in the region as he travels through rural towns and villages across China. He rarely spends more than one day in the same location, hitting the road again the next morning after photographing the site, gathering local villagers’ stories, and mapping out his route to the next location.

In 2012, Yang founded a non-profit organization with the aim of getting more people involved in his mission of cultural heritage documentation and protection. More than 6,000 people are registered as loosely organized volunteers across China in various grassroots projects such as recording oral histories from local residents. “I always thought that cultural protection was something far removed from myself, but later I realized that the goal of cultural protection can be many things, not only buildings,” one volunteer, Zhang Ying, tells TWOC.

“Some of the most successful projects I have been part of were oral history projects—successful not only in terms of recording the memories of the older generation, but also the process of engaging in dialogue with them,” adds Zhang.

What began as a hobby with friends from China and abroad in his early adult years around the turn of the millennium has slowly morphed into somewhat of an obsession for Yang, who has amassed vast amounts of digital records of thousands of places visited: a mountain cottage of the Ge people in Guizhou, flooded thousand-year-old towns by the Wujiang River, ruins of the Tubo Kingdom in Tibet, Muslim tombs facing the sea in Hainan, and more.

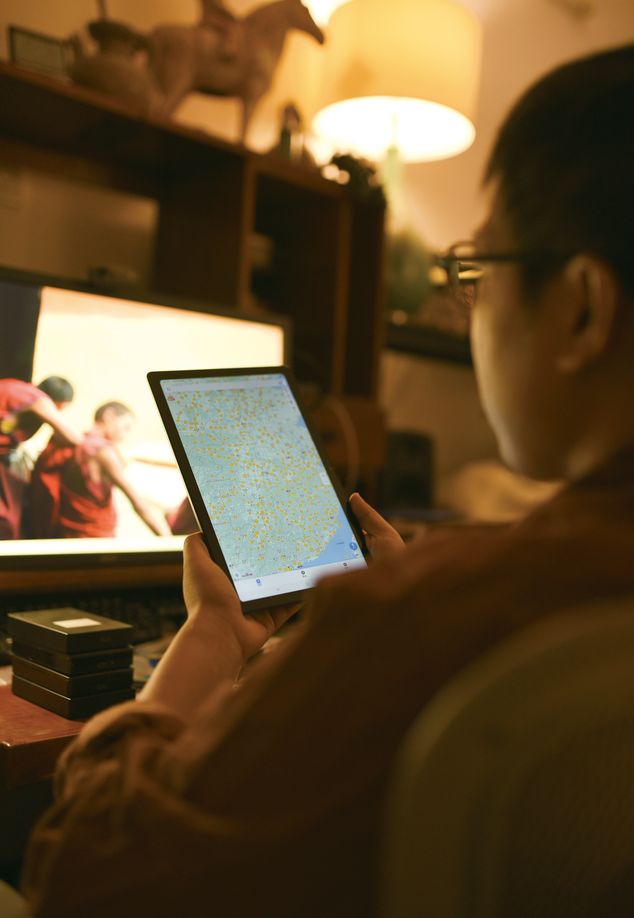

The maps on his phone are covered with countless stars representing saved locations: “I have taken a few million pictures over the years, and I always wonder if I should do something with them, but maybe this is just a way for me to approach these places,” Yang says. “Maybe this gives my life some purpose.”

The process of being there, engaging with the people, and creating digital records in itself may already help the cause. “Being present and documenting a place is an important first step, it helps raise awareness,” says Tan Jinhua, associate professor from the Institute for Guangdong Qiaoxiang Studies at Wuyi University, “because the protection of unregistered cultural relics in remote places depends largely on the efforts of the people there. That’s why raising awareness and education are vital.”

It is those places off the beaten path that Yang seems to find his purpose in most. In an old town in Sichuan, not too far from the Buddhist rock carvings, there is a street lined with historical wooden houses, old villagers playing cards or selling goods outside, and the smell of burned tobacco in the air. One man is hand-embossing “joss paper” money to be burned for the dead. “This man is 99 years old,” Yang learns from another villager. It brings a smile to Yang’s face.

This is where Yang seems to be entirely in his element: engaging people to hear their stories, taking pictures of everything he sees, always moving about to see and record as much as possible, the clicks of his camera’s shutter barely audible among the shuffling of playing cards and mahjong tiles in this small town somewhere in Sichuan.

The Relic Hunter: One Man’s Race to Save China’s Old Cultural Landscapes is a story from our issue, “Promised Land.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.