From cosmopolitan pictures to musical tourism advertisements, the Tianshan Film Studio once galvanized filmmaking in Xinjiang, but now struggles to regain its way

Bridges across deep valleys, highways snaking through passes, frontier fortifications guarding a vast landscape—drone shots take viewers over the border county of Taxkorgan on the westernmost edge of Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, in the 2022 film Why Are the Flowers So Red?

The name of the film is taken from a song adapted from a Tajik folk tune, and the answer to the titular question is revealed a few lines down in the song: “Because they were watered with the blood of youth.” The film’s hero is Laqini Bayika, a real-life Tajik border guard from a family that has protected the border high in the Pamir Mountains for three generations, who died saving a child who had fallen through a frozen lake.

If these clues don’t give it away, the logo in the opening credits, featuring majestic mountains, signifies the film as none other than a proud production of Tianshan Film Studio, Xinjiang’s state-owned film production powerhouse which has seen more than six decades of ups and downs as epic as some of the stories it has brought to the screen.

In 1949, the PRC was founded, and the cultural workers of the Communist Party arrived in Xinjiang to begin work on stitching the region’s peoples back into a nation. The Beijing Film Studio sent filmmakers to the region in 1950 to distribute newsreels and films and to shoot documentaries on life in Xinjiang for audiences far away.

The first film to be made in Xinjiang featuring the lives of ethnic groups was Hassan and Jamila (1955), a love story between two young Kazakhs which portrays their pastoral land as oppressed by feudal society. It was shot by the Shanghai Film Studio but made in close cooperation with cultural functionaries from Xinjiang’s ethnic groups, with the lead role going to a Kazakh translator at a local party office, who allegedly was taken aback that the lead actors wouldn’t be Han Chinese. “Had it not been for Chairman Mao and the Chinese Communist Party, we would have never dreamed [of playing our people onscreen]!” she exclaims in an interview with Chinese film magazine Popular Cinema.

Following Hassan and Jamila, the Ministry of Culture, in accordance with the nationality policy of the time which promoted ethnic identity and self-sufficiency in the arts among China’s ethnic groups, started encouraging Xinjiang filmmakers to produce their own films. They invited a group of 28 filmmakers and actors to tour studios in Beijing, Shanghai, and Changchun ahead of setting up their own film production center on the outskirts of Urumqi, the Xinjiang Film Studio, in 1956.

The studio would have two roles: producing films on topics relevant to local lifestyles and ethnic cultures, as well as dubbing and subtitling films produced by studios from the rest of China into Uyghur, the region’s second official language, as well as Kazakh and Kyrgyz.

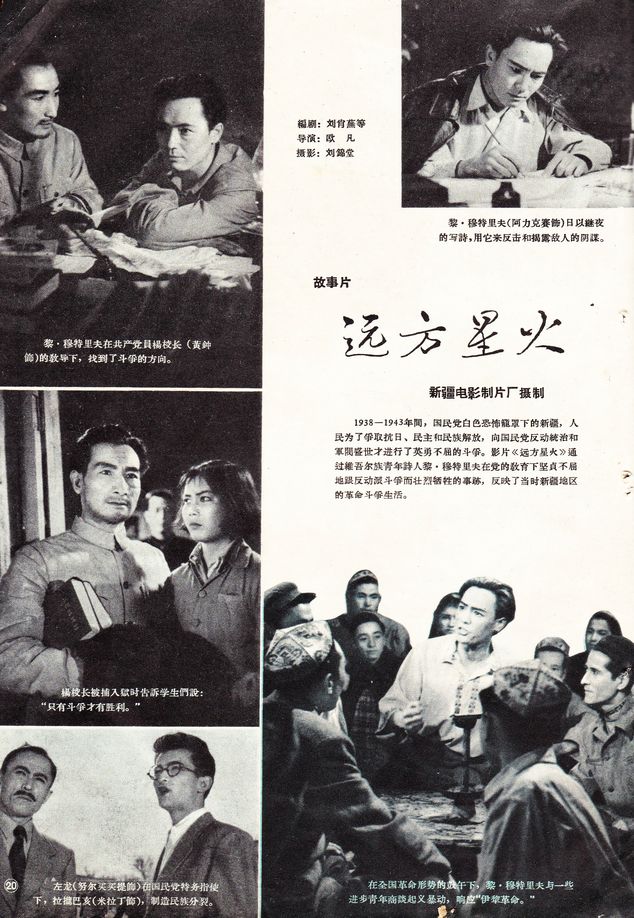

A Distant Spark (1961) is representative of the pictures they made: This reinterpretation of the biography of Uyghur poet Lutpulla Mutellip puts him at the center of the Communist Party resistance to Japanese imperialism and craven warlords. It was scripted by a Uyghur writer and shot with a local cast speaking their native language. The story unabashedly represents local culture: Lutpulla Mutellip is inspired not only by the socialist slogans of the underground, but also by a dutar player who he encounters singing a traditional epic in a local barbershop.

The studio only completed three of its own feature films before the economic difficulties of the 1950s and then the strict artistic policies of the Cultural Revolution made it difficult to organize production or release films for nearly two decades. But after the reforms began, the Xinjiang Film Studio was reborn, rechristened Tianshan Film Studio in 1978 after the famous Tianshan mountain range that cuts across central Xinjiang.

While early Tianshan pictures were still collaborations between Han Chinese and local ethnic talent, starting in 1978, the Beijing Film Academy allowed only non-Han film school graduates to be recruited to studios in Xinjiang and Inner Mongolia. At Tianshan, young Uyghur, Kazakh, and Uzbek filmmakers began making pictures pitched to their educated, young urban peers and global audiences.

This movement in filmmaking was led by Guang Chunlan. Born into a family of the Xibo ethnic group in Yining, Xinjiang in 1940, she was sent to work on a communal farm in Zhangjiakou, Hebei province after graduating from the Beijing Film Academy in early 1966. When film production began again in 1976, Guang bounced between several studios before returning to Xinjiang and entering Tianshan.

Rena’s Marriage (1982) tells a simple tale about a girl who wants to marry for love instead of accepting her parents’ choice of partner, a story inspired by Guang’s conversations with her Uyghur peers in the studio. “The ethnic minorities in Xinjiang craved the chance to express themselves and they were skilled performers. A few hints from the director would result in powerful acting,” Guang recalls in an interview two decades later with scholar Zhou Xia. “Since Rena’s Marriage criticized Xinjiang’s mercenary marriages, which everyone resented, I became even more welcomed and trusted by my Uyghur friends.”

The visual language of the film immediately stands out from Chinese film tradition. Mehrigul Amat, who plays the titular Rena, is strikingly beautiful, but not many Chinese starlets proudly flaunted a unibrow onscreen. The staging of the many song-and-dance numbers, featuring garishly technicolor mountain glade backdrops and carried out by performers from dance troupes and art schools native to Xinjiang, are closer in style to the Bollywood imports of the 1970s than the domestic revolutionary musicals of the ’50s.

A writer by the name Barley who seems to have grown up during the 90s recalls a favorite scene from seeing the film as a child: a main character plays the guitar and drinks with friends by the river “and ends being rude to his future mother-in-law...it was so Uyghur and so Ghulja [displaying the distinctive color of the Yining area]. It’s the kind of story that comedians here always riff on,” Barley writes in an article published by a Xinjiang-themed blog.

Guang’s next picture, The Reluctant Actress (1983), tells the story of a famous actress who sets out to find singers and dancers for her troupe but chances upon the daughter she gave up during the Cultural Revolution. Other than winning an Excellent Film Award from the Ministry of Culture that year, it was a surprise hit around Central Asia and as far away as Egypt. After a screening in Cairo, as Guang recalls, she was told by local foreign service staff that the audience “rushed into China’s embassy to express their excitement.”

As Guang recalled. “I further realized that there was so much to discover in Xinjiang, since it is home to 13 ethnic groups…I felt a whole new world was approaching. My works became more and more unrestrained,” she adds.

Other Tianshan talents soon followed suit. The studio produced stars like director and actor Achmed Tuigon, who was nominated for a Golden Rooster, one of the highest awards given by the China Film Association, for his role in That Money Thing (1985), then went on to direct and star in The Further Tales of Afanti (1991), a sequel to a 1979 film reimagining the popular folk tale of the Persian wise man Effendi. The film played an important role in making Afanti a household name in China even outside Xinjiang. Tianshan Film Studio became central to a cultural renaissance in Xinjiang, which was producing novelists, musicians, and poets who spoke to a new urban middle class.

Guang also continued to innovate, directing films like Crazy Dancer (1988), about break-dancers in Ürümqi, and Raging Youth (1993), about a young Uyghur fashion designer, which showed Xinjiang not as a frontier of reform policy, but as a thriving, cosmopolitan place: a center of experimentation, a window to the outside world.

These effervescent films about life in Xinjiang stand out from mainstream cinema with their local color and access to a unique base of local culture and performers, and they are also out of step with what other studios with a mandate to promote ethnic identity were doing: The Inner Mongolia Film Studio, which was also undergoing a renaissance, went in a more staid direction, producing pictures like On the Hunting Ground (1984), an experimental meditation helmed by auteur director Tian Zhuangzhuang, and the grim melodrama Senji Dema (1985). The pictures Guang made during this time have experienced a second life on streaming platforms (often only available now in the Uyghur language version).

Starting in 1984, the Chinese government began to cut funding for state film studios, leaving them to sink or swim, while restrictions on financing made it hard for these studios to secure outside funding for a picture.

That year supposedly saw a 10 percent decline in tickets sold compared to 1980, down to only 26 billion tickets, while in 1985, the number of moviegoers was down 30 percent. According to a 1988 report published by the China Film Association, only 34 of the 142 movies made in 1987 broke even or turned a profit.

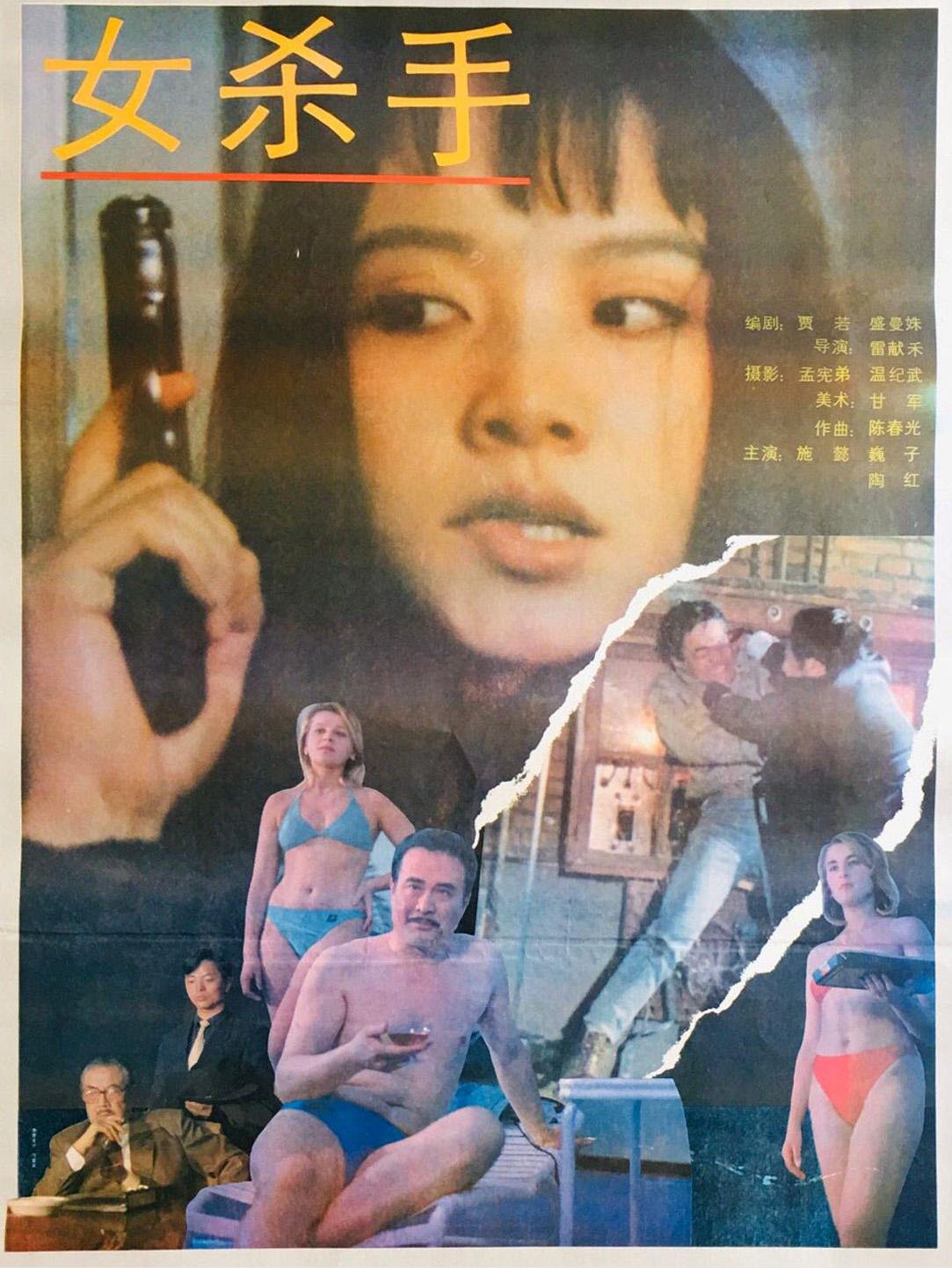

Tianshan was not spared. By the mid-1990s, decay began to set in. To pay the bills, the studio increasingly turned to renting out its brand to nominal co-productions. This is the era that gives us crass productions with the Tianshan name slapped on, such as Female Assassin (1992), an ultraviolent urban thriller featuring full-frontal nudity; and Macao Pursuit (1995), a relentlessly grim Hong Kong action rip-off.

Local audiences began to turn to television (satellite and domestic) and then to VHS tapes and VCDs of foreign and domestic films. While some talent drifted to television, where it was easier to earn a living and get pictures made, others sought opportunities in coastal areas. A number of local filmmakers also began producing their own work outside of the studio system, including Shirzat Yaqup, the husband of Mehrigul Amat from Rena’s Marriage.

Around 2002, the return of more robust state funding helped to turn things around. This sent the studio down a different path, toward patriotic and song-and-dance-heavy ethnic minority-themed pictures pitched to a mass audience, including viewers on the coast.

This new tradition has continued into recent years, with films like Wings of Song (2021), a vision of cross-cultural cooperation, narrating the story of young people from numerous ethnic groups trying to become artists, set against the backdrop of the azure prairies and modern cityscapes. However, it attracted some ruthless comments on Douban, for example, “I hope for a director’s cut that cuts out all the plot lines and only saves the scenery.”

Wings of Song and Why Are the Flowers so Red? demonstrate to different degrees the life left in Tianshan, but it seems that the studio has a long way to go to recapture the relevance it once had.