After lockdowns and gathering restrictions ravaged movie theaters across China, those remaining are looking for alternative business models to survive

It was a weekday at noon in November, when Chen Yan first saw a large group of people relaxing in the massage chairs in the lobby of Rainer Stars, the Chengdu cinema she manages. This gave her her next business idea: to rent out seats in the cinema’s nearly empty auditoriums to office workers for afternoon naps.

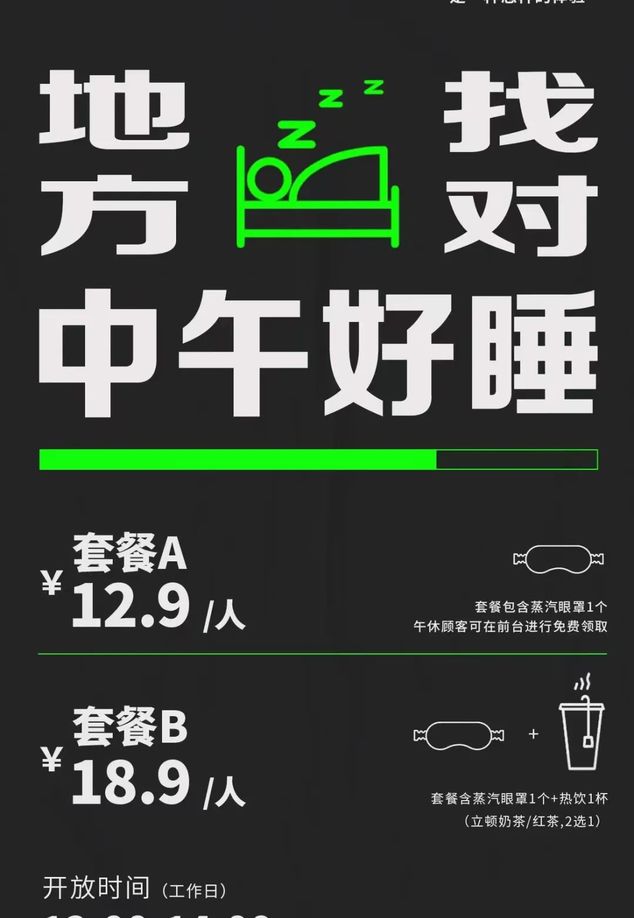

At a fee of 12.9 yuan for two hours with a complimentary steam eye-mask, or 18.9 yuan with a bubble tea added in, the “lunch break package” was a last-ditch effort by Chen to “earn some money to cover energy expenses” as the pandemic continued to ravage the business of movie theaters across the country. On November 21, the same day Chen announced her new initiative, Emperor Entertainment Group in Hong Kong stated that it would close all seven of its theaters in five cities on the Chinese mainland, only the latest cinema chain to exit the market in a year fraught with bankruptcies and cinema closures.

According to Dengta, a platform providing specialized data on China’s film industry, as of December 3, 2022, there are 5,792 movie theaters—around 46.6 percent of all cinemas in China—still operating in the country. With less than 20 days remaining in 2022, China’s once-soaring box office, formerly the biggest in the world, has only earned 30 billion yuan for the year, compared to over 60 billion yuan in 2019. After three years of the pandemic, which saw some cinemas closed for months at a time during citywide outbreaks—and struggling with occupancy limits and consumers less willing to go out or spend money after they reopen—many cinemas have thrown in the towel and closed for good, while others have begun innovative side businesses.

Located in Chengdu’s Hi-Tech Industrial Development Zone, which hosts the offices of internet giants like ByteDance, NetEase, Baidu, and Kuaishou, Chen had high hopes for the popularity of her new service among white-collar workers in the area. Two or three nappers purchased a lunch package on the first day, followed by six or seven the next day, including two social media “influencers,” but no one showed up on the third day—considerably below Chen’s prediction of 10 nappers per day. “There was an outbreak in Chengdu on the third day of the first week, and then [people] in the nearby office buildings started to work from home,” she says. On November 23, 547 new cases were recorded in Chengdu, and public places started requesting negative nucleic acid test results obtained within 24 hours to enter.

Besides the restrictions on gathering, the scarcity of film options is another reason why cinemas have had difficulty operating during the pandemic. Popular titles from this summer, such as Jurassic Park and the surprise domestic hit Lighting Up the Stars, attracted more than 1,000 cinemagoers a day to Rainer Stars—close to a record during the pandemic. In pre-pandemic times, Chen says her cinema could sell out all its tickets for blockbuster releases.

Movie production and distribution costs have risen during the pandemic, and Singapore’s Lianhe Zaobao reports that only 25 American films were imported into China in 2021, a significant decrease from the average of 45 to 55 films each year from the last decade. Highly anticipated Marvel titles like Spider-Man: No Way Home and Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness, and Top Gun: Maverick starring Tom Cruise, have not yet been released in Chinese theaters. “Actually, the number of people in the seats is deeply dependent on what kind of movies we offer,” says Chen, noting that due in part to the shortage of movies, only 30 viewers visited her cinema on November 29.

Some cinemas have tried to diversify their offerings with live shows. Chen Shenglong (no relation to Chen Yan), the owner of Kangaroo Comedy, a stand-up comedy production company based in Beijing, began receiving invitations in October to bring his team of over 10 comedians to perform in cinemas. Chen Shenglong and his team performed nearly 40 consecutive shows in Miruiku cinemas in Beijing from October to November 8, when Beijing once again started prohibiting all live performances due to rising Covid-19 cases.

From Monday through Thursday, each Kangaroo Comedy performance, which lasts 90 minutes, can sell around 70 tickets, while on Friday and weekends they can draw roughly 150 viewers, with tickets selling at 100 yuan on average. “The cinema and I are both happy with this collaboration, and they even helped me find more theaters [to perform in],” Chen Shenglong says.

In several second- and third-tier cities, cinemas had become significant venues for stand-up comedians even before the latest outbreaks. Since August, Tong Zhong, the owner of Mai Lang Comedy in Bengbu, a small Chinese city of 3 million people in the central Anhui province, has performed more than 30 stand-up comedy shows, the majority of which have taken place in a local cinema.

Smaller cities like Bengbu tend to lack theaters that are suitable for stand-up performances—bigger than a pub or a bookstore, but more affordable than an opera house or concert hall. Cinemas are ideal in Tong’s opinion because they are the most cost-effective venues. “In almost any third-tier city, [stand-up comedy] is generally performed in the cinema,” Tong tells TWOC.

But recently, while checking out the venues before his performances, Tong was saddened to discover how empty they were. “Every time I go to the cinema, as the staff show me around the venue, there are never more than five people there. Audience members all sit in the corner; if you don’t look carefully, you wouldn’t even notice them,” Tong says. His first stand-up comedy show in a movie theater drew an audience of nearly 200, with subsequent shows stabilizing at around 40 attendees who paid 70 yuan each for a ticket.

Some audience members were pleasantly surprised by the experience. Liu Yisha, a Chengdu resident who describes herself as a long-time fan of stand-up comedy and has seen over 30 performances in various cities since becoming infatuated with the art two years ago, didn’t have high expectations when she first purchased tickets to see a stand-up show in a Chengdu cinema in October. To her delight, she found that watching comedy while lounging on a wide sofa was more comfortable than watching on a hard bench in a bar or café. “[They offered sofas] as the featured service,” Liu tells TWOC.

For the comedians, the venue is more challenging. The distance between performer and audience is larger in a 200-seat cinema auditorium, especially for seats in the back, which makes routines that require audience interaction difficult. “Something the comedian performs in a small theater may be very funny, but then in the cinema it is not funny, so the comedian needs to be more skilled,” Chen Shenglong explains.

On December 7, China’s State Council released its updated “10 articles” on epidemic prevention and control measures. Many cities such as Shanghai, Hangzhou, and Chengdu no longer require nucleic acid testing to enter entertainment venues.

Despite restrictions being lifted, Chen Yan has decided to continue the lunch break service. Chen Shenglong also doesn’t want to give up performing in cinemas just yet, now that he has mature working relationships with a few theaters and a stable income. “If we get squeezed out [as cinemas start playing movies again], we will figure something out,” Chen Shenglong says. “We can go back to small theaters where we used to perform.”

With restrictions rolling back, China expects bankable blockbusters to revive the film industry starting with Avatar: The Way of Water, scheduled for release on December 16 in China. As of December 8, Avatar’s advance ticket sales exceeded 50 million in just one day.

Chen Yan is looking forward to screening this long-awaited release in her cinema—and hopefully, this time her customers will be wide awake in their seats. “First of all, people still like to watch blockbusters,” she says. “Second, at this juncture of the epidemic, it feels like a lifeline.”