A taste of opulence that supported generations of Chinese through an age of scarcity

When Hu Youzhen was in middle school in the 1970s, one of her most anticipated home-cooked treats was often a spoonful of pork fat hidden at the bottom of her bowl, served with her father’s affection and melted by the warmth of the rice on top.

Hu, who grew up in the county of Wuxue, Hubei province, as the oldest of four children, was given this special treat without her siblings’ knowledge because she had to walk 10 kilometers each way to and from school, where she boarded during the week. Her father, an alcohol distillery manager, thought the campus diet—mostly rice and 1 fen soup from the canteen, plus pickles brought from home—wasn’t enough to keep up her strength for her studies.

Whenever Hu found the glistening treasure in her rice, she would glance at her father, who would then throw back a look that “told me to keep it on the down low, so as not to upset my siblings,” Hu, now in her late 50s and an English teacher at a Beijing university, recalls. There wasn’t always enough to treat everyone in such a big family. “It was an age where we didn’t cook much with oil...We thought lard with rice was the most delicious thing in the world.”

Pork fat mixed with rice (猪油拌饭)—consisting of a chunk of jade-like solidified lard melting on a steaming bowl of rice, often completed with a dash of soy sauce and sprinkles of scallions—is not a culinary invention that any region in China cares to boast as its representative cuisine. But that doesn’t stop writers from devoting passionate words to its flavors.

In 2014, Nanjing Normal University Press published Fatty Meat, a collection of essays from around 100 authors who wrote about what this decadent cut of pork meant to them. In the essay “Revolutionary Fatty Meat,” author Chi Li recalled receiving a jar of lard as a token of gratitude for her work as a laborer and teacher in a small village in the 1970s. Painting a vivid picture of enjoying a small piece of lard with a bowl of steaming, newly harvested rice, seasoned with scallions and salt, on a snowy day, she writes, “One bite: suddenly, the mountains and waters were clear and beautiful, the wind gentle and sun charming, and the world became so lovely.”

Many people in China who lived through the era of planned economy and state-rationed food supplies in the mid-to-late 20th century recall waiting in long lines to buy meat and cooking oil, both rare commodities that had to be purchased with “meat stamps.” Anxiously eyeing the fattiest piece of pork hanging in the butchery window is a distinct memory for many, due to its scarcity. “You needed connections to be able to buy fatty meat,” writes poet Feng Xincheng in another essay in the collection, “Vulgar Fatty Meat and Proper Richness.”

Feng’s mother was in charge of the local meat and eggs counter, so he became the go-to person for all his neighbors’, classmates’, and even teachers’ purchasing needs. “The counter was always overcrowded, and I had to shout for my mother several times before she could hear me. Then she would tug a strip of fatty meat out from under the counter, and pass it to me over the forest of heads and hands.”

Cooking the fat out of the pork and preserving it in jars became a way to stretch out the little amount of meat families could get their hands on. “Raw pork fat, in a gleaming white, slowly melts at the bottom of the pot, oozing with lustrous clear grease,” writes director Chen Xiaoqing, born in 1965 and famed for his docuseries A Bite of China, in his contribution to the Fatty Meat collection. “The pieces of fat brown little by little, afloat in the oil while swimming softly.”

In Hu’s household, lard lived in an earthen jar “with a big belly...at least as big as my head,” she says. “We had this jar in the cabinet year round.” Also much-coveted by children was a side product: crackling. These crispy residues of cooked fat were enjoyed as a snack, dipped in salt or sugar, or saved for future use in stir-fried vegetables.

Adding small amounts of lard to rice or stir-fried dishes enhanced its flavor and gave meals a sense of ceremony. According to Hu, she grew up with tables filled with her father’s wild catches of fish from the nearby Yangtze River, or the beans, gourds, pumpkin, and eggplant they grew outside the house. “These things were not hard for us to get,” she says, “but meat was.” Lard was always there as a close substitute, sometimes just as a few drops floating on top of a soup to add flavor, which “my siblings fought over with spoons,” she remembers, laughing.

Lard became a potent symbol of opulence. A well-known rural legend in China, often repeated by older generations, tells of a man who used to put a bit of lard on his lips every day when he left his house in order to appear like he had just eaten meat, so that people would think he was rich. In some retellings, that worked almost too well: The man was classified as a “rich landlord” during the land reform in the 1950s and got into trouble during the Cultural Revolution.

With improved access to food in the last two decades of the 20th century, people in China started to look at lard with more suspicion. Lard is higher in saturated fat than many other oils, experts warn, which puts those who eat it at higher risk of obesity and cardiovascular disease. The once-prized treat was thus relegated to a health nightmare or a guilty pleasure. (More recently, some nutritionists have suggested lard was unfairly maligned and isn’t necessarily less healthy than other types of fat—and may even produce fewer toxins under the high-temperature stir-frying common in Chinese cooking.)

Lard could be making a comeback on the strength of nostalgia. Hema Fresh, a grocery delivery app popular among the urban middle class, came out with its own lavishly branded lard—with labels featuring brush calligraphy and a square of wax paper tied around the cap of the jar with twine. This example of vintage, boutique down-to-earthness sells at 34.9 yuan for a 428 gram jar.

Also fueling this “lard renaissance” are some high-end restaurants in Shanghai, which have given lard mixed with rice a makeover with sea urchin, truffle, or Spanish ham, setting willing customers back hundreds of yuan for each bowl.

“My daughter was born in 1989. Families were better-off then, so lard didn’t taste that good anymore,” says Hu. But some customers at Tong Fat Tou Restaurant, a Hong Kong-style cafe chain popular on social media, which boasts lard with rice as one of its signature dishes, might disagree. Almost 50 years since that snowy day when Chi Li enjoyed her bowl of lard on rice, one Shanghai diner on review app Dianping waited more than four hours to dine at Tong Fat Tou, but channeled the same spirit in a glowing recommendation of the dish: “One bite goes to your soul.”

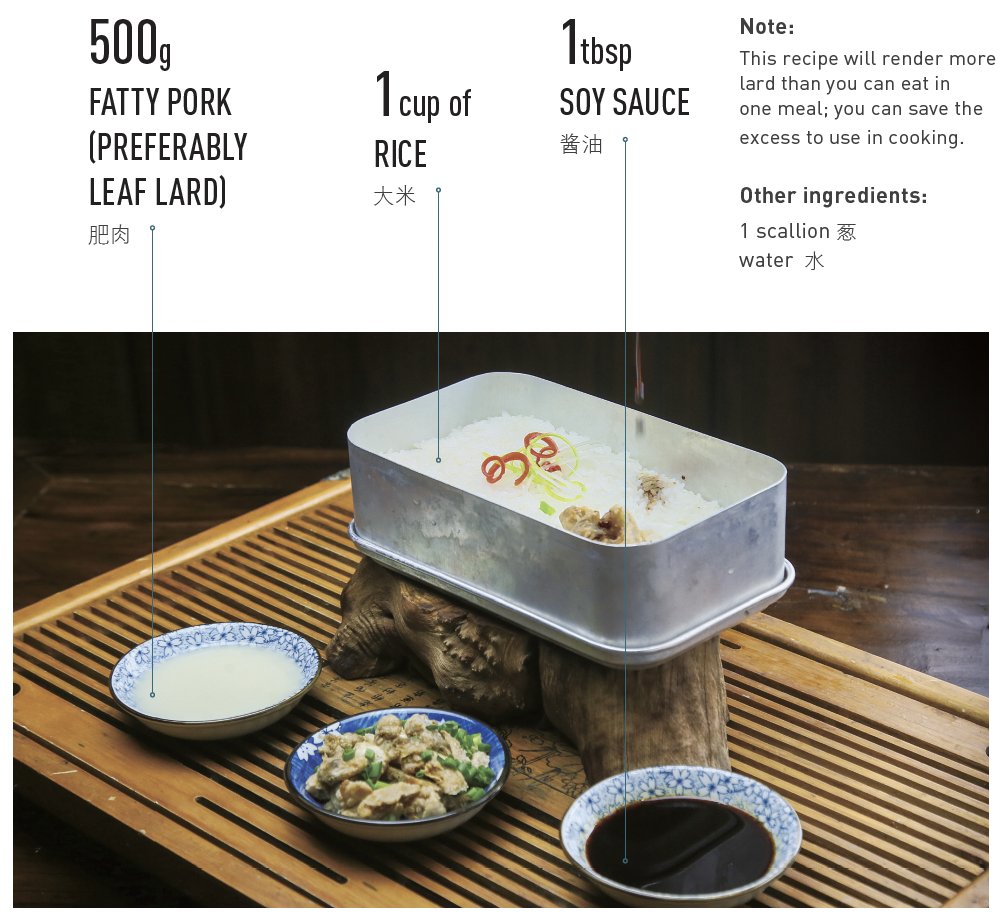

Recipe:

- Cut the fatty pork into small cubes.

- Place pork cubes in a pot, add some water to prevent the bottom pieces from burning.

- Slowly cook the pork on low heat. Oily liquid will start to form, while the pork bits brown and shrink into crackling. Stir often to cook evenly and prevent sticking.

- While the pork cooks, wash and cook some rice.

- When the crackling appears golden, strain oil into a container. Let it cool at room temperature. Cook the crackling on the side.

- Take a spoonful of solidified white lard, place it on top of a bowl of rice. Add soy sauce and scallions.

- Stir and enjoy.

Leftover lard and crackling can be saved for stir-fries, soups, and pastries.

Note: This recipe will render more lard than you can eat in one meal; you can save the excess to use in cooking.

Larder Than Life: Pork Fat With Rice Brings Memories of a Bygone Era is a story from our issue, “The Data Age.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.