How 50-year-old “cleaning auntie” Wang Liuyun discovered freedom in painting

Our narrator today is Wang Liuyun, a janitor working in an office building in central Beijing. Her daily shift starts at 6 in the morning, and sees her scrubbing down everything—from toilets to stairs, conference rooms to sinks, railings, and windowsills—before the end of the day.

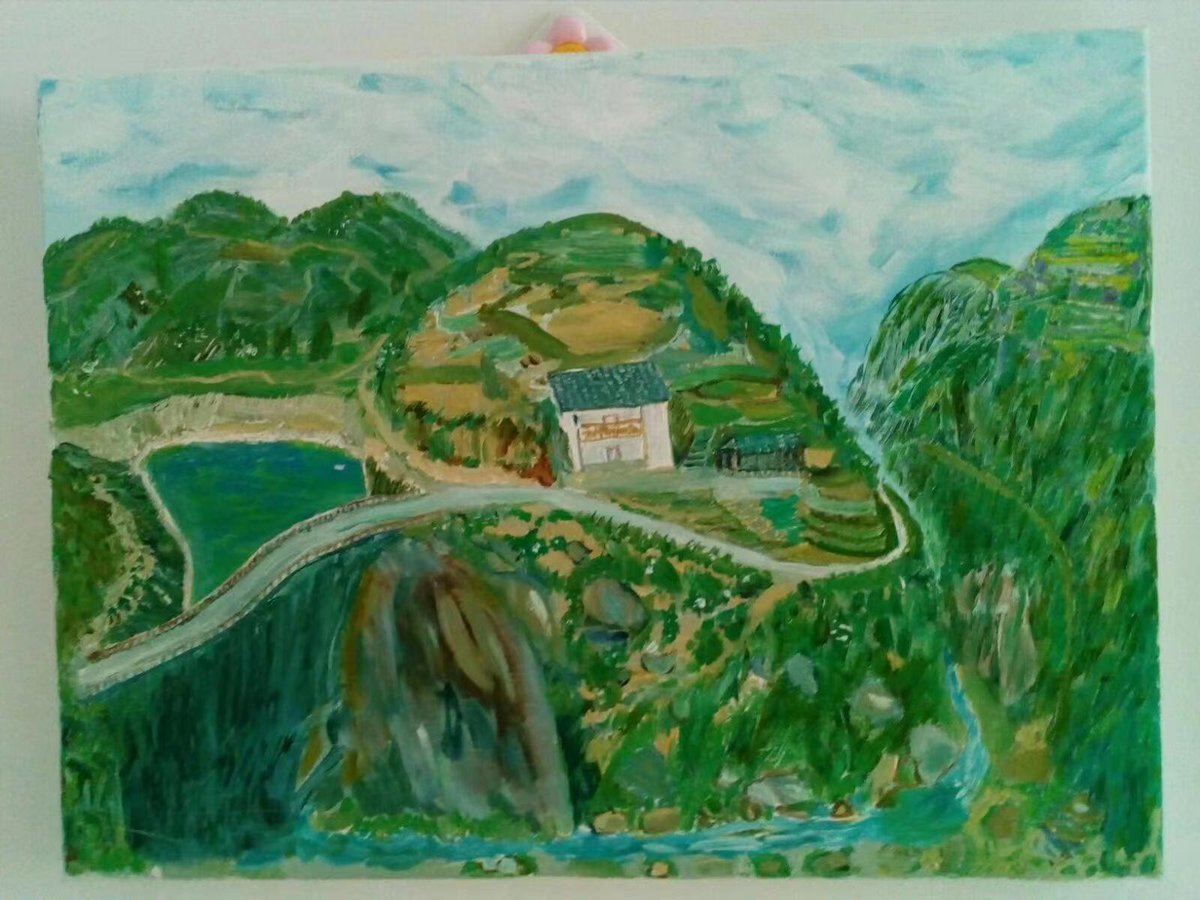

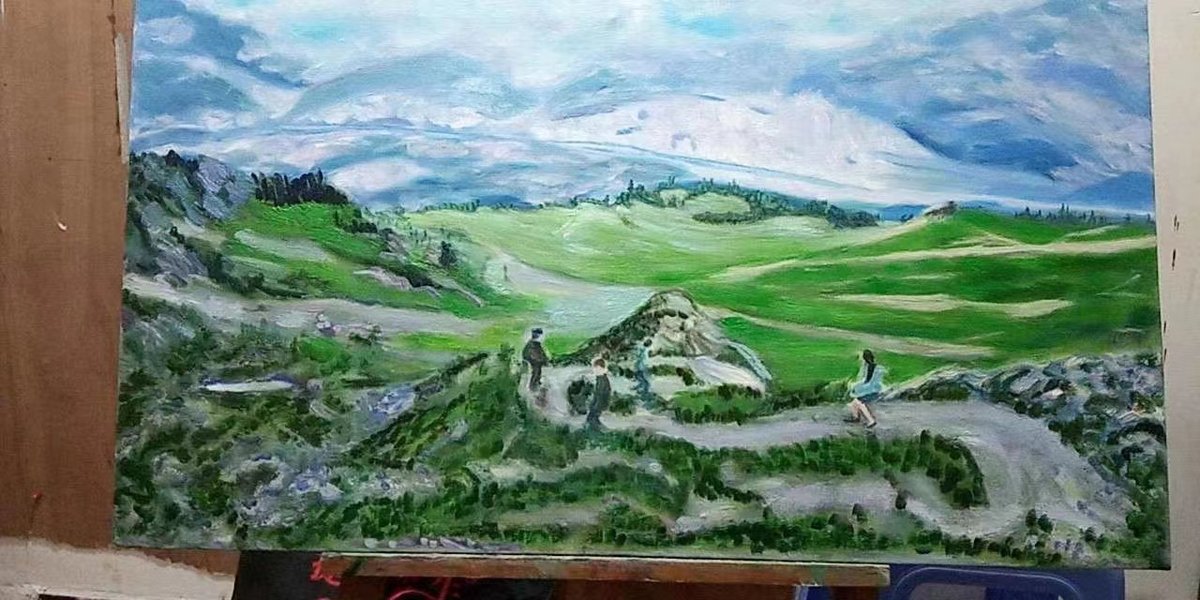

But this is not Ms. Wang’s only identity: She is also a painter. In her spare time, she picks up her brush, dips it in her palette and creates a whole new world. Mountains, rivers and lakes, birds and beasts—all these subjects flow out, one brushstroke at a time.

It all started with a decision she made when she was 50 years old.

Wang Liuyun was born to a peasant family in 1967 in Xinhua county, Hunan province. She was a smart girl who was fond of books. However, her father had a disability and the family was in dire straits, so Wang had to drop out of high school.

Her marriage was not any easier. Her first husband was abusive and cheated on her. She escaped, but her second marriage was just as unfortunate. Wang’s second husband was a weak, apathetic man who never contributed anything to their household. She worked on a factory’s assembly line, then in a hotel, and in a restaurant. Now, she cleans offices. Wang has worked in some capacity pretty much every day of her life, but she remains poor.

She felt as though she was trapped in a cage.

So how did an inexperienced janitor, without any art education, discover painting? Did it really free her from her prison and help her find fulfillment? This is Wang Liuyun’s story.

-1-

“Anyone Can Be an Artist”

I think I was fated to paint.

I watched this documentary on CCTV Channel 9 that focused on a free painting course taking place in Shuangxi, an ancient town in Fujian province. Anyone could go to this town and be an artist there. I was just really curious, and I found myself yearning to go. Painting has always felt like this lofty profession. I always imagined painters as being inside high-rise buildings where we never get to see them. But here I was presented with this big, open studio where lots of people were painting their hearts out.

There was this older woman well into her 60s that really caught my attention in the documentary. Though she was dressed shabbily, she was in the studio painting a picture of a kerosene lamp. It was missing its lampshade, and it was placed in the center of the room for students to paint it.

My eyes were glued on that old lady and her repeated attempts to paint the kerosene lamp. She failed for three consecutive days, and you could tell she was very disappointed. But a week passed and she actually managed to finish the painting.

I thought it was amazing. Here’s this old woman, who had no education at all, and she still found a way to learn.

Then, I told myself: No matter what, I must go.

Back then, I was still working in our home county. Sometimes I’d be a waitress at some hotel, sometimes I was on dish duty at a restaurant. Yet I always felt that my whole life was lacking a purpose. It just seemed as though I lived to work, barely making enough to support my family and myself. I was bored out of my mind. I felt like I was in prison, too. All I wanted was some time for myself—to read a little, or take a walk somewhere nice.

So, I just kept thinking, No matter what, I must go.

-2-

Discovering My Talent

I finally arrived in Pingnan on March 8, 2017, after the New Year holidays.

Once I got to the studio, a young assistant gave me three drawing boards and two brushes. We shared all the pigments as well as the easels, and there was plenty to go around. You just went there, grabbed whatever materials people left out, and started painting.

I had my mind set on painting the kerosene lamp. I’d seen it on TV so many times, so I wanted to see how good I was in comparison to the others.

I was excited at first, but when I was done, it looked nothing like a lamp. The base of the kerosene lamp showed this transition between different hues of brown, due to rust. But when I painted it, it just came out as this huge mess.

What could I do? I wanted some help, so I looked for the assistant, but he wouldn’t teach me either. Everyone said that there was no point in teaching, and the only things of value were those that came from your own imagination.

All the assistant said was that my painting was good. I couldn’t draw for shit, and this guy was telling me it was good.

I had no choice but to force myself to keep painting.

I thought back to my childhood, when we didn’t even have electricity. I thought of the kerosene lamps we lit back then, with their dim light. I tried to imagine how one of those lamps looked when it was all lit up, and then I mixed some paints until I got the orange and red hues I saw in my mind’s eye. The closer to the light source, the brighter the color, so, I started painting a circle at a time, gradually moving away from the center of the light. Once I got that going, I tackled the base of the lamp.

The assistant instructor came over to take a look and said that my painting was excellent; dreamlike, even.

Story FM: After a few hours of painting, Wang completed her first canvas: an old kerosene lamp. She didn’t think it was any good, but at least it was done. She felt she could keep going.

The next day, she completed two new paintings of a broken bench and a bouquet of violets. On the third day, she painted the hats typically worn by local farmers. This time, her works attracted the attention of Lin Zhenglu, the director of the studio.

Lin Zhenglu started off as an art merchant before he set up this charitable studio for the residents of the villages and small communities that dotted Pingnan county. Not only did he believe that “everyone is an artist,” he also thought that every student should draw “whatever is interesting to them.”

Among his students were farmers and people with disabilities, as well as middle-class folks and youngsters from the cities. Lin Zhenglu provided them with a venue and painting tools, and then sold their works online.

This was the case for one of Wang Liuyun’s paintings, sold for 150 yuan.

Teacher Lin started paying attention to what I was doing, and came to see me paint every day.

He said, “Wow, well done. Now this is talent.”

For me, it wasn’t about the money. It was a matter of building up my self-confidence.

I wanted to prove that I could do it, that I have talent. I’d never painted anything before, I’d never taken lessons. I’d never even thought about painting before.

-3-

Letting Myself Live a Little

Wang had first come to Shuangxi because she was curious. She only had some 300 yuan on her when she arrived. All she’d wanted was to stay there for a few days and check whether the studio really was anything like the miraculous place from the TV. However, all the affirmation from her peers had now boosted her confidence, and she wanted to stay there to continue learning.

The staff also encouraged her to hold an exhibition once she had completed 10 or so paintings.

But after a week, Wang Liuyun only had enough money left for a train ticket home.

I felt so confident that I hurried back to my hometown and borrowed 5,000 yuan from the credit union.

Why take out a loan, you may ask? It’s not like I had any other choice. My family had always relied on me as their sole breadwinner, since my husband is not in good health. We’ve spent every cent in building a house and raising the kids. That’s all my wages ever stretched for.

When I left Shuangxi, I was planning on going back to keep learning. It looked like I had some talent, after all. That’s why I went back home. I planned on working and making some more money to fund my next stay.

I have suffered enough throughout my life. I have no dreams left to fulfill, other than maybe enjoying myself. I love painting. It allows me to recreate the landscapes and rivers I like. Whenever I saw the stream flowing over the riverbed, making ripples, I felt happy.

Back in Shuangxi, Wang lived in a hotel for 20 yuan a day. Her daughter bought her an induction cooker online, so that she could make her meals in a pot in a corner downstairs. Life was rough, but fun. Wang got up every morning after 5 to bike or walk to the town and village and sketch there. Once she sketched out the landscape, she went back to the studio to paint.

All in all, she had a happy time.

-4-

“If You Stay Where You Are, You Stagnate”

Wang had seemingly found a way to escape her depression, to flee from the cage of her reality. Painting helped her leave behind the poverty and frustrations of her real life, and even the pains in her body. Her eyes were filled with the scenes she contemplated and the visible improvements in her own painting skills.

But real life wasn’t going anywhere. Three months later, Wang ran out of the money she’d borrowed, so she had to go back home.

Some five days after I returned home, Mr. Lin sent two people to look for me and bring me back to the studio. He gave me over 10,000 yuan and said it was the price for selling a few dozen of my paintings. He gave me the money up front, just so that I could go back to my painting lessons. Then we put all my paintings online on the platform and sold them all at once.

I still felt uncertain about my decision. Would I still be able to continue supporting myself by painting?

I went around town every morning. When I saw a house I liked, I greeted the owners and went inside to check the structure of the house: like the color of the tiles, or the way the eaves curled on the roof.

The fourth floor in these houses is usually the attic, and usually covered in a layer of dust. Standing there, I felt like a mouse. I loved studying those houses.

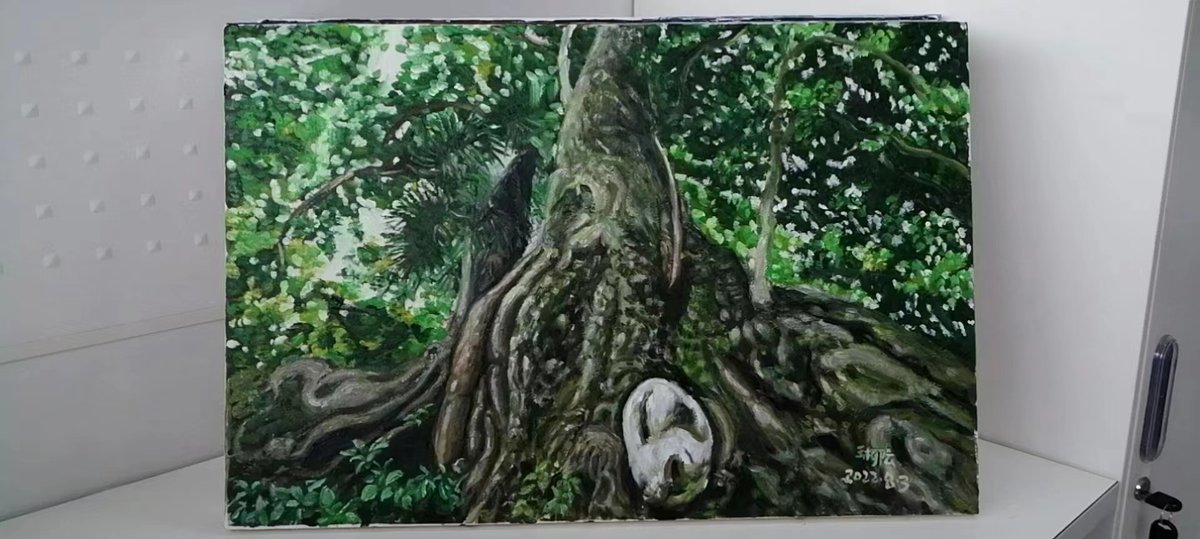

I also wanted to paint the mountains. There were surrounding villages, waterfalls, small streams, 90-degree vertical cliffs and those odd, weather-beaten trees. Those trees were my favorite, because they look good when you paint them all crooked like that.

At first, I didn’t have a mobile phone to take photos with, so I just sketched the outlines in a notebook and wrote down the color of everything. Then I went back to the studio and quickly drew the rest from memory.

Before I came here, I used to be very depressed. I’d work in this or that factory, or wash vegetables in a restaurant, and all the time I’d just think about the upcoming payday, the way we’d spend it right away on this and that, and my husband’s debt.

That was painful, just like slashing your flesh with a knife. But now that I was painting, everything felt different.

Painting is so enjoyable. I would stand still in the waterfall, thinking about the running water, the color of the moss or the dipped stones under the stream, and I wouldn’t think about anything else.

Just like that, I let go of everything and everyone that is unpleasant. When I looked at a person, they couldn’t bother me. They had nothing to do with me. That was the source of all my pain—a great burden I’d always carried with me.

That year, Lin’s studio and its painters—many of them rural women and people with disabilities—went viral online. Tens of thousands of people came to visit. Wang Liuyun was the studio’s bestselling artist, cashing over 40,000 yuan in two or three months.

But this fame was fleeting. Fall came, and Wang felt she was having a hard time selling her paintings. She gradually gave up the idea of selling her art for a living, and assumed she’d have to go back to menial jobs after all. Another source of frustration was the way that she had to study on her own, without any formal guidance.

Though Mr. Lin repeatedly tried to get her to stay, Wang decided to leave by the end of the year.

During that boom period, I moved out of my rented lodgings and lived in the studio, where I had two floors all to myself, with all water and electricity bills covered. I only had to pay my own meager living expenses. I could have spent many peaceful years just like that.

The way Lin Zhenglu saw it, I was a born artist. He said I had to follow my calling, and that I would reach it only if I stayed in the studio.

But I decided against doing that.

Just how was I going to learn anything else without a teacher? I was always on my own, and there are only so many times you can draw your surroundings before you reach a dead end. Just like water needs to always spurt from a fresh spring, so do we humans need fresh grounds to evolve and thrive. If you just stay where you are, you stagnate.

-5-

Like a Knife in My Guts

Where was Wang to find new sources of growth and inspiration? The next leg of her journey took her to Dafen village in Shenzhen, Guangdong province. Dafen has long been famous for its cottage industry, concentrating thousands of painters reproducing world-famous oil paintings for sale, like an assembly line.

There were those who tried to advise Wang Liuyun against joining the ranks at Dafen, claiming that she’d spoil her pure, natural talent there. However, she was excited to go there. To Wang, it was a new world where she had all kinds of painting schools, techniques, and people at her disposal, from renowned painters who’ve starred in documentaries to those who merely filled in the base color and drew some flowers on the canvas. She felt that everyone in Dafen was her teacher.

What did I do in Dafen? I copied famous paintings. I remember that for my first task I copied a fragment of Huang Gongwang’s “Dwelling in the Fuchun Mountains,” a legendary black-and-white shanshui (landscape) ink painting that I helped recreate in oil paints. I really had to use my brains with that one.

For example, back then I couldn’t really draw light and shadow. I noticed when I started painting this huge, leafy tree growing on a field. The color changed from the middle of the tree upward as light and shadow rushed in, but I couldn’t reflect any of that in my work.

I was way out of my league, and it felt very, very painful.

The learning curve here unearthed a lot of hidden pain for me, and it was pretty hard. It felt like swallowing a rusty, deformed steel blade, one that I couldn’t spit out nor remove. I woke up in the middle of the night, sighing with pain.

I had to solve this painful conundrum. And the only way to do that was to keep learning.

Back then, Wang Liuyun bought many books on oil painting, and even apprenticed herself to a master whose skills she observed in her frequent walks in the village. She also observed her landlord, who was likewise in the trade. She also enjoyed watching people paint at the town square. At first, she stood far away from the action, but after a while, she boldly approached the artists to learn some tricks from them.

In addition to painting, Wang Liuyun also worked odd jobs at the local hotel to support herself. She felt a sense of urgency—as if she had to hurry up and make the most of every day. She improved her skills by leaps and bounds, but in the end, her financial circumstances forced her to give up Dafen and her aspirations.

While I was learning to paint, my husband had managed to run up a huge debt—20,000 yuan. So, I hurried back home and went to work immediately.

At home, my husband was like this statue. I was running around all day, racking my brains to find a way to have a better life, or even just to survive, and he just sat there. It was better that we didn’t see each other. When I saw him, I went purple with rage.

Dafen is a small place, where everyone knew one other. I had stopped making progress with my painting, and I couldn’t sell any of my works. I became a laughingstock; everyone gossiped about what I did.

I just couldn’t really keep up. Going there, going back home, everything I did felt like this knife in my guts.

-6-

Out of the Frying Pan into the Fire

After studying painting in Fujian and Shenzhen for nearly two years, all Wang Liuyun wanted was to break free from the cage of reality, but in the end this wasn’t to be. In her own words, she was always on the go and eventually just wound up jumping out of the frying pan and into the fire.

In order to repay her husband’s debt, Wang returned home to work for six months. She couldn’t bear to live there. Finally, the second half of the year came with an offer for Wang to teach art at a school in Henan. Though the wages were low, at least she could still draw while she taught.

But her new occupation came to an abrupt end in early 2020, when the epidemic first broke out across the country and forced schools and educational centers to close. And at this worst possible time, another challenge reared its ugly head—her husband had run up yet another huge debt while she was away working as a teacher.

By the end of the Chinese New Year holidays, the whole country was shut down. As for myself, one month is all I could survive before I ran out of food to boil in my pot and stopped being able to afford gas.

I was worried sick. I asked my husband for advice, but he couldn’t care less. He literally slept through it all. He did what he’d always done— sat around, humming to himself. If I died, he’d probably make me dig a hole to bury myself in. He was like some cold-blooded animal. He didn’t even care about himself.

In her desperation, Wang Liuyun thought that the only chance left for her was to move to Beijing and work there. Back in Henan, she had met a woman who’d promised to help her out if ever she went to Beijing, so she called up this acquaintance and asked to stay at her place for a bit while she settled in. Wang bought the cheapest train ticket she could find and went to Beijing, where she found work in an office building as a janitor as soon as the initial lockdown was over.

At that time, Wang Liuyun had a bunk in a room shared with six other people. The space was cramped, full of old clothes, tea jugs, jars and containers of rice, oil, and salt. She felt suffocated. It was impossible to paint in such an environment.

The cleaning staff there was made up of some 50 or 60 people, and we all had to huddle in a room about a third of the size of this recording studio to eat our meals, as if we were a flock of chickens and ducks at some farm. The space was crowded and stank of our sweat, and there were a lot of old guys who said all sorts of nasty stuff.

Needless to say, we couldn’t work all day long, but go tell that to the supervisors, who chased you around the minute they saw you taking a break. It really was just like they were chasing chickens, ducks, and dogs. We had no sense of belonging.

They didn’t see you as a person. We were just tools to these people. We had no right to speak, we were not entitled to think. It was even worse than the exploitation of surplus value described in Marx’s Das Kapital. So, I was at an all-time low.

Right around that time, I met some folks in Beijing who told me about hourly jobs I could pick up on Sundays at various places around the city. At first, my reasoning was that if only I made some more money, I’d be able to afford a better place, so I accepted.

But quickly, I stopped going. Some bosses have no conscience at all. They’ll make you pack three days’ worth of work in a single day, chasing your ass down wherever you work, dragging you everywhere to work more, more, more. That kind of pace, you can only put up with for so long before you drop dead. They just don’t treat you like a human being.

Damn, I remember this one time I was working somewhere downtown. On my way back to my place in the suburbs after a full day of work, I fainted. I puked my guts out on the stop, and it took me a while to even get back on my feet.

At that moment, I made up my mind. Even if I starved to death, I wouldn’t do this kind of work anymore.

-7-

Pulling Myself Out of That Hell

A year later, Wang finally managed to rent a room in an “urban village” close to her workplace. Though the space was tiny, just six square meters, she could now set up an easel in the corner and resume her painting.

Though I practically lived in a cubicle, somehow I managed to free up one square meter for my painting. On Sundays, or evenings after work, I started working on my canvases again. I went at it really slowly; I was in a bad mood at that time. But I had to pull myself out of that hell. If I wanted to work toward a normal state of mind, I would have to do so myself.

I want to pursue spiritual freedom for the rest of my life. I don’t want to work my life away at some factory or wherever else, just to support myself. I don’t find anything of interest in living like that. This race to eke out a living had made me so miserable.

When I paint, it’s like I create this space for my soul to dump every burden. My previous depressive episodes, my sadness, my despair, they haven’t gone anywhere; they’re the same as always. But now I have a place to put them down for a while.

Shortly after resuming her painting, Wang Liuyun changed jobs. This time, she was treated much better. Her new employers even set aside a lounge for her. Though it was barely three square meters, Wang Liuyun was thrilled. She paints there every day after her shift, and on her days off too.

When she’s painting, she’s not constrained by this tiny space. She’s free in the landscape of her imagination—climbing up mountains, swayed by the sea, carried away by the murmur of some stream and its gentle ripples.

Though painting never quite granted her a ticket away from reality as she’d originally hoped it would, Wang Liuyun did notice a change—not in her life, but in her heart.

Indeed, for the first half of her life she was burdened with her lot; she felt imprisoned in her own life, entangled in her husband’s apathy. But now Wang Liuyun feels that painting is also part of her destiny.

Every human being has a destiny. For example, I am destined to provide for my family just as someone else is destined to play mahjong all day long. I love painting, and painting loves me. So, that’s why I can do it. Painting makes me happy.

As long as you have a mind of your own and a vision, you can paint. I’ve been observing nature all my life, so when I paint it’s just as a poet once wrote: “My body is a pile of fallen leaves”—my body is full of thoughts and visions of all kinds. When I lift my brush, it’s as if a butterfly is flying out the window.