Renowned documentary director Gu Tao recounts his journey into indie filmmaking and his years living with Ewenki herders in northern China

We live in a modern society now.

It’s swallowed us up.

Our hunting culture

is disappearing.

Society is becoming industrialized

and turning the world into

a miserable place.

If the police of a more civilized world

shoot at me,

then I’ll say

“Go ahead, shoot!”

—Weijia, former Ewenki hunter

Three hundred years ago, a tribe known as the Ewenki migrated with their reindeer herd from Siberia to the northwestern foot of the Greater Khingan Range.

On August 20, 2022, Ewenki chief Maria Suo, known as “China’s last female chieftain,” died at the age of 101.

In the words of the former Ewenki hunters, a people that lose their own culture are a people bound to lose everything. The Ewenki are certainly acquainted with loss—whether brought on by alcohol abuse, forced domestication as a byproduct of our modern civilization, or the dissolution of their collective identity.

Today’s narrator is Gu Tao, a filmmaker with Manchu, Mongolian, and Ewenki heritage, who decided to depict the Ewenki and their lives in a trilogy of documentaries starting in 2004—Aoluguya, Aoluguya, The Last Moose of Aoluguya, and Yuguo and His Mother. Armed with his camera, Gu spent eight years alongside this hunting tribe, capturing many precious and candid images, but also raw and even shocking moments.

Gu is a name to know in China’s indie documentary scene, a free spirit with plenty of stories to tell. To understand his work better, it might be useful to delve into his background first. In Songzhuang, a suburb of Beijing famous for its concentration of artists, Gu built two yurts to serve as his living quarters on some farmland, and he’s been living there on his own unique, environmentally friendly terms. For instance, he’s gotten rid of mirrors. He argued that he saw no point in using them, but in the greater scheme of things, it was more of a symbol of his rejection of external references and projections.

However, Gu’s coming of age as a child in the 1970s took place in a period of dramatic changes for China. The turmoil of the times sent Gu into his own dark night of the soul, and it was only in his mid-30s that he finally discovered his calling as a filmmaker. Today, he sits down with Story FM to talk about the follies of his youth and the turning point that set him on a soul-searching journey, where he found unexpected stories in the heights of the Greater Khingan Range.

-1-

Into the Woods

I am Gu Tao, a film director focusing mostly on documentaries. I also have many other interests—I draw and write, and I even keep a personal diary. But my one true calling has been documenting the living conditions and mental health challenges of the northern ethnic groups in China’s modern society.

I was born by the foot of Xishan, the so-called “West Mountains,” in Hailar district, Hulunbuir, in northeastern Inner Mongolia. Come spring every year, when the Indian azaleas bloom, the slopes of Xishan turn into a sea of pink.

I spent my childhood running up and down the mountains with my friends, playing macabre games with the exposed coffins that were lined up on the slopes all too often back then. We were a bunch of brats who played this game where we jumped over the coffins. The boldest among us got to be proclaimed the eldest brother, closely followed by the second, third, fourth and so on. When my turn came to jump, I managed to land foot first on the poor devil’s remains in the one coffin that happened to be in pretty bad shape. I scrambled to my feet, and I couldn’t act scared. I didn’t want to be the youngest brother.

It’s all woods further to the west. And, just a few hundred kilometers into the taiga, you bump into what used to be the hunting grounds of the three main northern ethnic groups—the Oroqen, the Ewenki, and the Daur. They all lived there, deep in the woods.

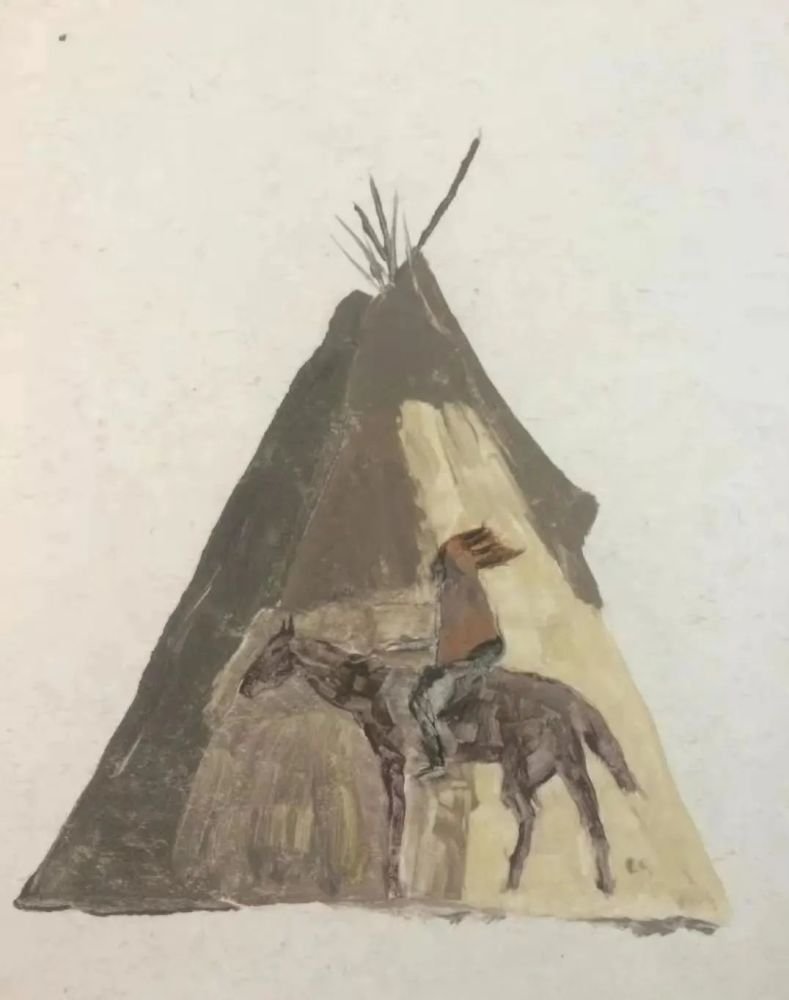

I was born there because my dad, Gu Deqing, moved to the area way back in the day. He used to work in the fine arts department of the local cultural center. When Old Gu was a child, he got this illustrated magazine featuring a burly forest hunter, perched on his horse. He was red-faced with these high cheekbones, wearing a headpiece with horns while holding a rifle. This image stayed with my dad.

Later, he found out that the man was meant to be a hunter from one of these ethnic tribes. That’s all it took to bring him to this area.

In his youth, my dad looked kind of like I do now: sporting long hair and even a beard. Or at least he did for a while, before he decided to shave it all to go deep in the woods, where he joined a bunch of these hunters for a few months.

Sometimes, he came back from these hunting adventures with this guy armed with a rifle who turned out to be a chief of the Ewenki, of the only reindeer-herding tribe in China. I would hide behind the door that was ajar, silently peeping on the two men as they drank together with reddened eyes.

-2-

A Certain Generation in a Certain Time

Gu Deqing perceived that the times were changing much too fast for these northern ethnic groups. As a result, their lifestyle, clothing, food, housing, means of transportation, and even their collective mental health had all been affected. At first, Gu Deqing immortalized these groups on his canvases. However, he soon switched to photography in order to keep up with the times.

This was all happening in the 1980s, right around the time China underwent significant reforms and finally started opening up to the world. However, this whirlwind meant that the whole of Chinese society was about to be reshaped. Gu Deqing knew as much from his observation of the different ethnic groups, and this much he was also aware of—he had to make sure that Gu Tao, his son, was ready.

My teenage years were rocky.

My dad always made sure that I had some homework before leaving home on duty. Draw this, write that, that kind of stuff. It shouldn’t have been a big deal to me. Kids always enjoy drawing. But I just wasn’t your average kid, I guess. We had this wood stack in our yard, standing at the height of about two men. My sister would climb to the top and stand watch there so that she could call out for me when our dad was coming back. Then I’d rush inside the house to pick up my pen where I’d dropped it and play the good student, all sweaty from the run.

I was always sneaking out, and it didn’t take long before I started drinking in my teenage years. It’s not like the adults around me gave a damn. Well, my dad sure did. Once he caught me lying around, drunk as hell without a single care in the world, or at least I was until he beat the crap out of me.

So, inevitably I told myself I’d run away.

And, I really did. I don’t remember whether it was 1985 or 1986, but I was in high school when a classmate came up to me with the idea. We hid under the train seats and somehow managed to evade paying fares all the way up to Jagdaqi district, about 30 kilometers away. It wasn’t very far away, but it already felt like the world’s edge, because my world back then was tiny.

We ate and drank our fill, and we soon ran out of money, so we decided to steal stuff to sell for cash. My classmate located the most expensive shop around, a stall selling winter clothing, and tasked me with chatting up the cashier to distract him. Out of the corner of my eye, I saw my classmate running away with a whole stack of trench coats. My legs went numb, and I remember thinking, Wow, I’m a real thief now. But, of course I legged it myself.

Well, we made a grand total of 35 yuan out of one of the coats before someone else robbed us of the rest of our loot. We tried to rob a bakery next, but this time the cops handcuffed us and we were brought to their quarters at the train station. There, we joined this dude who was still holding a large knife in his hand.

Eventually, they shipped us back home. We’d only been away for some four or five days at that point.

It’s really over for me, I thought. They’re going to kill me at home.

It turns out I never got so much as a slap for my escapade. Instead, I woke up in the middle of the night to the loving hands of my folks turning me over to check whether I had any injuries or signs of abuse. When they saw I was fine, they let me fall back asleep.

The next day, I woke up to a brand new shirt by my bed. Black and red plaid, the trendy style back then. My dad never even scolded me.

Now, I’m grateful for the way he raised me. Without my dad there, I probably would have grown up to be a petty thief. One thing’s true, though. That’s what life was like back in those days. Just look at my childhood playmates. Some ended up beating people to death, some took the beating themselves, and yet others took things into their own hands and drank themselves to death. We were children of our times. Those years just about ate us whole, you know?

-3-

What Will You Do When You Grow Up?

There’s this other anecdote from a day my dad and I were walking home on a really harsh winter day.

My dad had clocked off his job and we were on our way back home, stepping on the snow that was already hardening. Without any street lamps around, it was a really dark night. Then, all of a sudden, my dad asked, “What will you do when you grow up?”

Now, I reckon kids never give a real answer to this kind of question. They know it’s all about saying whatever the grown-ups want to hear.

I said, “Guess I’ll become an artist.”

My dad just grunted.

I turned 18 years old in 1988. That’s also when my dad came to me and said, “Alright then, if you’re going to become an artist, painting is the way to go, and you’ll have to get out of here for that.” So, I chose to study painting in Harbin.

There I was, leaving home for good this time.

In 1992, I visited Beijing for a taste of the outside world. That’s what the capital was to me back then. I wanted to see what people were up to in this big city.

I was pretty impressed. At that time, the only McDonald’s in China was right there in Wangfujing Street. People were queuing like crazy at the entrance, and it was just as packed inside.

I checked the price on the banners—a 4 followed by a 27. I took that to mean 4 yuan, 2 mao and 7 fen. That sure was pricey, but to hell with it, I told myself. I had 10 yuan in my pocket.

I was carrying my painting folder when I squeezed in and waited for my turn to order a meal set for the advertised price of 4.27 yuan. However, it seemed like the waitress couldn’t care less, so I had to insist. “Hey, comrade! I want the one for 4.27, pretty please.”

She replied in a thick Beijing accent. “Huh? What are you on about? Check today’s date!”

That’s when I took another look at the banner and finally got my head out of my ass. It was April 27, 1992—4.27. Damn, that wasn’t the price. Okay, I didn’t get that far only to leave empty-handed, right? So I worked up the nerve to ask for the cheapest item on their menu.

Sixteen yuan and eight mao—16.8.

Now that was completely out of my budget, so I squirmed my way out of the crowd and back onto the streets.

-4-

Greasy Revenge

Gu had been sitting the university entrance exams since 1988. By 1992, he had already sat four rounds, and even the test itself had evolved—there was a new English section, and it was now a multiple choice exam.

Finally, in 1992, Gu was admitted to Inner Mongolia University’s art college.

After graduating, Gu caught up quickly with the interior decorating craze in China. From hotels to family homes, everyone in this brand new era placed great value in personalized decoration. Gu wanted to jump on the gravy train that he’d seen many of his fellow newly graduated colleagues riding, and for a while he did. Had he persevered, well, he’d probably have built something a little fancier than a simple yurt in Songzhuang.

You probably are wondering by now—why didn’t he do just that?

Put a little money in people’s pockets and they go crazy. My colleagues and I, we feasted, we drank, and we created. Back in ’96 or ’97, when we were hired to make a sign for a hotel, we usually just slapped some words on foam boards, painted them, and added some small accents. Two or three days of work and we pocketed over 2,000 yuan, at a time when the average monthly wages weren’t much more than a few hundred.

Sure, we didn’t sweat it to make our money back then, but it was even easier to spend it, and that’s exactly what we did after a short while.

Then, one of us went to Beijing for work and triggered our big northern exodus in 1999. Soon enough, I left Hohhot for the capital with a bunch of friends. We were all a bit dazed arriving in Beijing with our big fat purse—some 50,000 yuan we had. That really was a ton of money back then, something like 500,000 yuan nowadays.

You’d best believe we started spending money as soon as we hopped off the train. One of us got this fancy leather jacket from a hawker, and a really cool one at that, some seven or eight hundred a pop, but that thing reeked of mutton. Wear one of those a couple times and good luck getting rid of that stink!

Anyway, my buddy asked me, “Hey, man, where do we go to grab a bite?”

That was an easy one to answer. “McDonald’s!”

I stuffed my face with like five Big Macs and then I got all dizzy, but I didn’t give a damn. Some greasy revenge that was.

Anyhow, it’s no wonder we went broke after maybe half a month. In the end, we couldn’t afford to hire workers for the project we had in mind, so we ended up losing money when the project got canceled. My buddies all headed back to Hohhot, but I stayed behind. I thought Beijing was fascinating—a world apart from our narrow bubble in Inner Mongolia.

Back then, you only had two kinds of people in Inner Mongolia—the drunkards and the teetotallers. But I was meeting all sorts of people in Beijing.

I was living in the basement of Anhui Beili in the Asian Games Village. I got a bunch of neighbors: scriptwriters in our basement, an assortment of rock ’n’ roll guys, chicks galore, and even hairdressers. Not that I wasn’t pleased. This is some good fun, I told myself.

I made my way up gradually from the very guts of our building to the first-level basement, fitted with a window that must have measured some 20 cm, straddling the frontier between the ground above and the underground levels. From this privileged location, I could see young lovebirds sitting on street benches, or rather, their legs all entangled. Just like going to the movies!

Yes, even from my basement I could smell the intoxicating scent of all this culture and art taking over Beijing.

-5-

Something Artsy in the Air

Gu’s lofty ideals spilled from his basement abode, but as always he soon found himself running out of money. Eventually, he decided to take up photography, though he had trouble settling on a consistent theme. Fashion and industrial PVC pipes became his first subjects, and before he knew it, he was doing commercial photography and was about as far as he could possibly be from his artistic ideals.

This didn’t sit well with young Gu. He’d inadvertently come to define success as the act of making money with meaning, in direct opposition to Chinese society’s idealization of money as success in the ’90s.

However, Gu himself was a living contradiction. Though he was all about finding meaning, in this era of lavish money for some and sharp class differences for others, he often resented his lack of material prosperity.

At this point, he also hated the basement that had once appealed to him.

You see, there was this guy named Liu Huan living on the 11th floor of our building. He ran an acupuncture business and every time he’d come back from work, he’d park his car and leisurely smoke before heading upstairs.

Meanwhile, we all burrowed underground like a bunch of little mice.

We’re a weird bunch, us humans. We say we don’t want money to lord us over, but deep down we still want to make a buck. Yet we’ll still whine if it doesn’t come from some cool, fulfilling job. This really got me thinking. I wasn’t willing to just do whatever for money, even if it proved profitable. Just in 2001, I made 20,000 yuan from commercial photography alone. Well, it still felt empty. It never felt like my thing. Above all, it never felt like art. I grew antsy, and that was no good. I’m not necessarily proud of the stuff I do when I’m anxious.

I spent most of that decade between 25 and 35 years of age in this daze. Maybe that sounds like this kind of utopia. Whatever utopia means, anyway. I’m not too sure myself.

My drinking was also at an all-time high, though it’s not like I was drinking alone. In hindsight, that whole moment in time seems soaked in alcohol.

I remember my former classmates and their fancy habits. They drove BMWs and Mercedes-Benzes and wore slippers; they got drunk and ran all around Wangfujing Street when they did. Some fucking breezy, romantic lives they lived, or so I used to think.

So yeah, that’s the way we lived back then. I’d bumble my day away like the drunkard ass I was until I got to down the next bottle of booze, and then I’d hit my basement nook, where I’d stare at the ceiling all lonely instead of ever really resting. I couldn’t come up with a purpose for my life, and as my 30s approached I realized I had no damn idea what to do for the next decade. I spent more time drunk than sober, and even when I wasn’t drunk I just felt emptier than ever before.

There was one time I got proper pissed and was burning by the time I got home. I went straight to our fridge and took everything out—a tub of miso paste, a block of tofu, and some leftovers. Then, I stuck my head inside and just quite literally chilled there. I only remember that it felt very cool. That, and my wife coming back home and pulling my dumb head out of there. My hair was all white and she had to slap me twice to bring me back to my senses.

Just a ton of drinking back then, you know?

There was also this time I smashed a beer bottle on my head. We’d been drinking tons, of course, and then we started discussing art. Eventually, I felt as though art couldn’t possibly be a subject of discussion, so hey, I just smashed that bottle on my head instead. I almost killed myself. I bled so much, they filled half a basin from the blood they squeezed out of the mop they’d used to clean the mess.

I guess it wasn’t real pain, though. When you’re young you’re just idling your time away. I can only imagine I’d really have killed myself had it been real, legit pain.

-6-

Returning Home

Around this time, independent photography and documentaries began to flourish in China. Gu became acquainted with the likes of directors such as Liu Zheng, Wu Wenguang, and Jia Zhangke. They all focused on different topics for their work—power imbalances, the prison system, or public expression, among others.

Eventually, Gu decided to take back the reins of his life and go back to his instincts. Where was the point of photographing the grasslands when his roots belonged in the mountains?

In 2002, I went back home to the Greater Khingan Range for the first time in four years. Things had changed a lot in my absence. To begin with, time had done a number on my dad. His hair was now white, his legs all bent, and his back all hunched. The comparison between my unchanged looks and the way he looked now got me down something fierce.

That’s when I came across Diary of a Hunter’s Life, the book my dad had published in 2000. It’s not like I was in the dark about it. In fact, I’d helped him compile his actual diary when I was in junior high school, though I hadn’t read it at the time. I’d left home when I was 18 and it was only now, at 32 and back at my parents’ house, that I really got around to read it.

Turns out, I was instantly hooked. I couldn’t wait to visit my dad’s old stomping grounds to photograph everything, get a taste of his life some two decades ago, and meet his old friends and acquaintances. So, on the second day of the Chinese New Year holidays, I went to Aoluguya, an ethnic township that is home to the Ewenki tribe. I only brought with me my camera and a letter penned by my dad by means of introduction.

Speaking of that letter, it listed quite a few Russian-sounding names—a guy named Maxim, for instance, and Maria Suo herself, the last matriarch of the Ewenki. It wasn’t until I arrived in Aoluguya that I learned that most of those people had already passed. Only Ms. Suo was still alive, and so I set out for her son’s house down the mountain.

As it soon turned out, the timing of my visit couldn’t have been more fateful if I’d tried.

The Ewenki originally lived in the woods, where they hunted in tune with the seasons. They devoted themselves to reindeer husbandry and overall lived in harmony with nature. However, with the start of the 1990s came an increase in illegal activities by foreign poachers and loggers. Starting in 2003, the Ewenki were told to move out of the mountains for ecological protection, and to hand over the hunting rifles they’d carried for generations. I arrived in Aoluguya on the very eve of this event.

Very few of the Ewenki had ventured outside their community, and my dad had managed to remain friends with many of them over the last few years. Many folks came to see me, and in the end it became a full-blown meetup.

I remember this teapot doing the rounds as we all drank in circles. Some of the Ewenki broke out in tears. They were supposed to lead the reindeer down from the mountain the next year to thin out the herd. However, now that they had to hand over their rifles, their ecosystem of sorts would be effectively disrupted. This meant real, significant change was coming the way of the Ewenki people.

I felt grieved that all I could do was sit there to drink and mourn with them. And then this scene unfolded right in front of my eyes—this pair of old hounds were mating in our hosts’ living room. Suddenly I was seized by life in all of its rawness—all these living creatures drinking, bumping into each other, crying our eyes out, being in heat, shagging right in front of us. Sadness and passion, all mixed together. There was no way in hell I could capture all of this in a single image. Nothing short of a documentary could adequately capture the Ewenki, their lives and their fate.

From that very moment on, change sprouted in my heart.

-7-

Weijia the Hunter

Of course, Gu didn’t change overnight. In order to secure all the necessary filming equipment, he took a job in a magazine, only to end up wasting another two years. Gu had spent his early adulthood fearing he’d die waiting for everything he needed to make his goals happen—whether it was money, equipment, or the right timing.

In 2004, Gu felt he’d had enough. He made up his mind to act, no matter the consequences. He borrowed a camcorder and jumped lens first into his documentary career.

For money, he alternated between periods of working in Beijing and his stays at the Greater Khingan Range. As soon as he earned some money, he returned to film in Aoluguya where he became a shadow to the Ewenki, and returned to Beijing again when it ran out. All in all, it took Gu some eight years to complete his documentary series on the Ewenki. He persevered because he felt that this work was instinctive to him. In the forest, he felt he could breathe again, and when he was among the people of the forest, he felt he was experiencing the most authentic form of truth.

Gu shared with us at Story FM the stories of three members of this ethnic group. First is the story of an Ewenki hunter called Weijia, who was deeply impacted by the hunting ban. To make sense of the end of his days as a hunter, he turned to poetry and painting, but also—and more importantly—to alcohol.

When I first met Weijia, I thought he was a very lively guy, as well as a lot of fun to talk to. Nobody would have guessed, with his slumped nose and beady eyes, that he had plenty of great stories about his time up in the mountains.

When the hunting ban brought his occupation to an end, Weijia started working as a janitor at Aoluguya’s detention center, but he didn’t last long. Whenever he saw an Ewenki inmate, he took them out for a meal, simply because he thought the food at the detention center wasn’t any good.

He was then demoted to telephone operator, but once again he fell short of the expectations. The constant ringing annoyed Weijia so much that he unplugged the whole thing and just sat there drinking by himself. Soon enough, complaints poured in.

With every passing day at the detention center, Weijia felt that he was doing himself wrong. In the end, he left and returned to the mountains.

Just listening to this, I already knew that Weijia was no ordinary guy. This kind of unfettered freedom is at the very core of the Ewenki’s temperament. Their lifestyle informed their daily routine. Hunting and animal husbandry were key aspects to their culture. Their herds were peaceful—no quarreling between the females, nor even between animals in rut. Prior to the hunting ban, things really went by as smoothly as possible for these folks. Then the ban was enforced and you had men like Weijia, sitting in this detention center where he was meant to do stuff based on a whole different set of rules. He just couldn’t do it.

Weijia was still a hunter at heart, and he wasn’t having anyone forcibly removing his identity. He ran into the woods with his hunting rifle, closed his eyes, and tried to jump into a ditch. This wasn’t his first suicide attempt, but he didn’t die this time either. He got caught in a tree.

Without his gun, Weijia began to drink. Sometimes I saw him sitting motionless by the campfire for hours on end. Whenever you touched him, he’d say, “Leave me alone. I’m looking at the hunter in the fire. I can see a dead hunter in the fire.”

The Greater Khingan Range is where the Ewenki people’s ancestors reside.

When I was young

I rode the reindeer with my mother

along the Aoluguya River,

our dzu tents like great Pyramids.

People there

were in harmony with nature.

Their spirits were one.

I remember

they sang the song of thanks

to the red sun in the east.

And the song carried the charm of the Ewenki language.

We live in a modern society now.

It’s swallowed us up.

Our hunting culture

is disappearing.

Society is becoming industrialized

and turning the world into

a miserable place.

If the police of a more civilized world

shoot at me,

then I’ll say

“Go ahead, shoot!”

—poem by Weijia

Weijia always said that if they took his rifles, he’d kill himself. He finally made good on this threat in 2017.

On that day, he’d been binge-drinking with a group of people on the mountain. He became haunted by hallucinations, and took a hunting knife and walked away from his group until he was deep into the woods. Then he sliced his belly open—the way Japanese do in the ritual known as seppuku—pulling the knife from bottom to top and then sideways.

Later he recalled that after slashing himself twice, a large cloud in the sky took the shape of a man, who stretched out his hand to drag him up. But as the sun began to set, Weijia had yet to die. The moon climbed up the mountain, and he still wasn’t dead.

But Weijia did feel very cold from losing so much blood, so he somehow managed to walk back to his group, covering his stomach. At first, some of them thought he was hiding a bottle of wine, until he let go and exposed his terrible wound with his intestines all hanging out. Everyone rushed to take him to the hospital, where a doctor later said that if he hadn’t grown up in the forest, he couldn’t have stayed alive for so long.

-8-

The Specter of Alcohol

Though the forest was a source of vitality for Weijia, it also trapped him in his alcoholism.

He was hardly alone in his habits. The mortality rate for both the Ewenki and Oroqen peoples is unnatural and ranks among the highest of all ethnic groups in China. Over 80 percent of these unnatural deaths are related to alcoholism.

In the words of both Weijia and Chief Maria Suo’s son, He Xie: “How many of us have drunk themselves to death, ever since the golden days in old Aoluguya up until now? We’re dying like flies, and it’s all because of alcohol.” Alcoholism had also taken the life of He Xie’s younger brother.

But here’s the thing: When you’re forced to watch, powerless, as your world and culture disappear, alcohol is going to find a place in your life.

The Ewenki had lost an important part of their lives, so you got these people desperate to find a new reason to keep on living and losing themselves to alcohol instead. After all, alcohol was the only thing that could take them back to the hunting days of old.

I’m a drinker myself, but I do wonder how long I’d be able to stay in the woods if I didn’t have booze to keep me company.

The forest can be this terribly lonely place where all you can hear is the sound of deer bells and the wind blowing through the leaves. When the Ewenki had their shotguns, they could at least hunt. But now, all they have is this deafening silence exacerbating their loneliness and emptiness.

So, booze becomes part of this daily routine, if only as a way to get a little closer to death with each passing day.

Eventually, we had to hide the alcohol. There was this reindeer researcher who came from Harbin with a few bottles on him, but then found that there was way too much drinking going on in the mountains, so he ended up climbing a tree and hanging the bottles there.

After three days, it was impossible to locate the alcohol. In fact, for a while everyone struggled to even find the tree. In the end, short of being able to actually climb, Liuxia—the protagonist of my second story—had to saw the tree down to get her hands on the bottles.

-9-

Liuxia and Her Son

Liuxia is Weijia’s sister. Two years after Liuxia gave birth to her son Yuguo, her only child, her husband died after falling into a ravine.

This tragedy pushed Liuxia into alcoholism. Yuguo’s grandmother was worried sick that an increasingly unstable Liuxia wouldn’t be able to raise the child. When Yuguo was 6 or 7 years old, he was sent to a boarding school in Wuxi in southern China under the Communist Youth League’s “Project Hope” initiative for educating underprivileged kids.

Not only had Liuxia lost her husband—now she was also separated from her child.

By the time I met Liuxia in 2004, she had already grown round and plump. The weight she’d put on her face had squeezed her eyes into slits, and her cheekbones were quite prominent, but I found her to be very pretty. Her legs were bent, and she had two steel plates placed in her body as a result of a beating she got for stealing someone else’s alcohol.

In my eyes, Liuxia became this poetic mother figure of the woods. She’d doted on her son, but now her child was far away from her, so she only had the sun, moon, and stars to pour her love upon.

She always said herself that “The sun is my mother, the moon is my father, and the stars are my son.” In fact, those words were spoken by Yuguo when he was little. They lingered in Liuxia’s heart, and she never forgot them.

In truth, Liuxia originally wanted to call Yuguo “Schiwun,” the word for “sun” in the Ewenki language. Alcohol has a way of making her talk about the kid. She will call to him, “Little Yuguo, you are my sun. Spread your wings and come back to the woods, so that I can hug you and love you.” Liuxia muttered those words, like many other people mumble to themselves in the forest. Folks in the city would think you’ve lost your mind, but here in these woods, soaked in alcohol and loneliness, the people all talk to themselves.

Liuxia often lay down in her cone-shaped tent after drinking, letting the scorching summer sun shine on her face until the oily, sweaty skin gleamed. Beneath the sun, she felt as though her son was watching her. She often reached out with her hands to catch the sunlight.

She could have turned her back just a little to avoid such strong exposure to the sun, except that’s not what Liuxia wanted. You would always find her wherever the sun was shining—no matter how hot or dazzling it was.

The scene drove me to tears.

-10-

Yuguo’s Holiday

Gu was uneasy as he perceived Liuxia’s challenges as a mother without her child in the forest, so when Yuguo was 13, he decided to bring the boy back to Liuxia’s side for a while, even if only to spend a short school holiday with his mother in their native forest.

This is Gu’s third story for us today—Yuguo’s holiday.

When I went to fetch Yuguo from school, I realized this significant change in him the farther we went north, and the closer we got to the Greater Khingan Range. He started sleeping on the floor rather than on his sleeper, and when we went to eat hotpot, he pointed at the raw meat we hadn’t cooked yet and asked whether he could just eat it like that. When I replied that he could do that if he wanted, he just up and put the slice in his mouth.

It was like seeing his roots as the child of a hunting people slowly awaken after they’d gone dormant in his blood and bones.

When we finally arrived in the settlement down the mountain, we actually ran into Liuxia, who’d already been downing her daily bottles and was now about to go to a neighbor’s house. Just as she bent over the fence, she found that Yuguo was back. At first, Liuxia didn’t even know how to hug or kiss the boy. She was stunned.

Yuguo was also at a loss, but broke out of his daze when Liuxia finally hugged him, only to gradually pull him down to the ground. “Mom, you’re drinking too much again.”

Liuxia hurriedly replied, “No, no, I was just really happy to see you.”

Had this been a movie, no director would have been able to direct such a scene. That much I can tell you.

In 2009, Yuguo spent his entire winter break, including the New Year holidays, in the mountains with Liuxia. I can only imagine that this was the warmest year Liuxia had known in a while.

But school was about to start again, and Yuguo had to go. Liuxia was very reluctant to part with him. Yuguo would tell her to go home, but she just wouldn’t. She struggled with this unspoken farewell.

In the end, though, Yuguo had to leave. Liuxia was bitterly disappointed. She raised her eyes to look at the sun shining in the sky.

And that’s the last shot of Yuguo and His Mother.

When it comes to issues such as alcohol abuse, identity loss, and the domestication of any given culture, Gu’s documentaries have added value in the sense that they’re not simply depicting the struggle of these northern ethnic groups in today’s society. From a sociological and anthropological angle, we can also reflect on the way our own ways of life have become a forced mainstream and come to terms with the painful, rough side of modernization.

However, Gu doesn’t try to exalt or elaborate on anything throughout his works. He just records it all with great care and an objective, balanced approach.

We recommend that you check out his documentary series for yourself. The best part is, you don’t even need to spend money to do it. You can simply visit Gu Tao in Songzhuang. He’ll be sure to welcome you to his yurt for a private viewing.