Can films and literature from the Northwest shake their strong association with rural subjects?

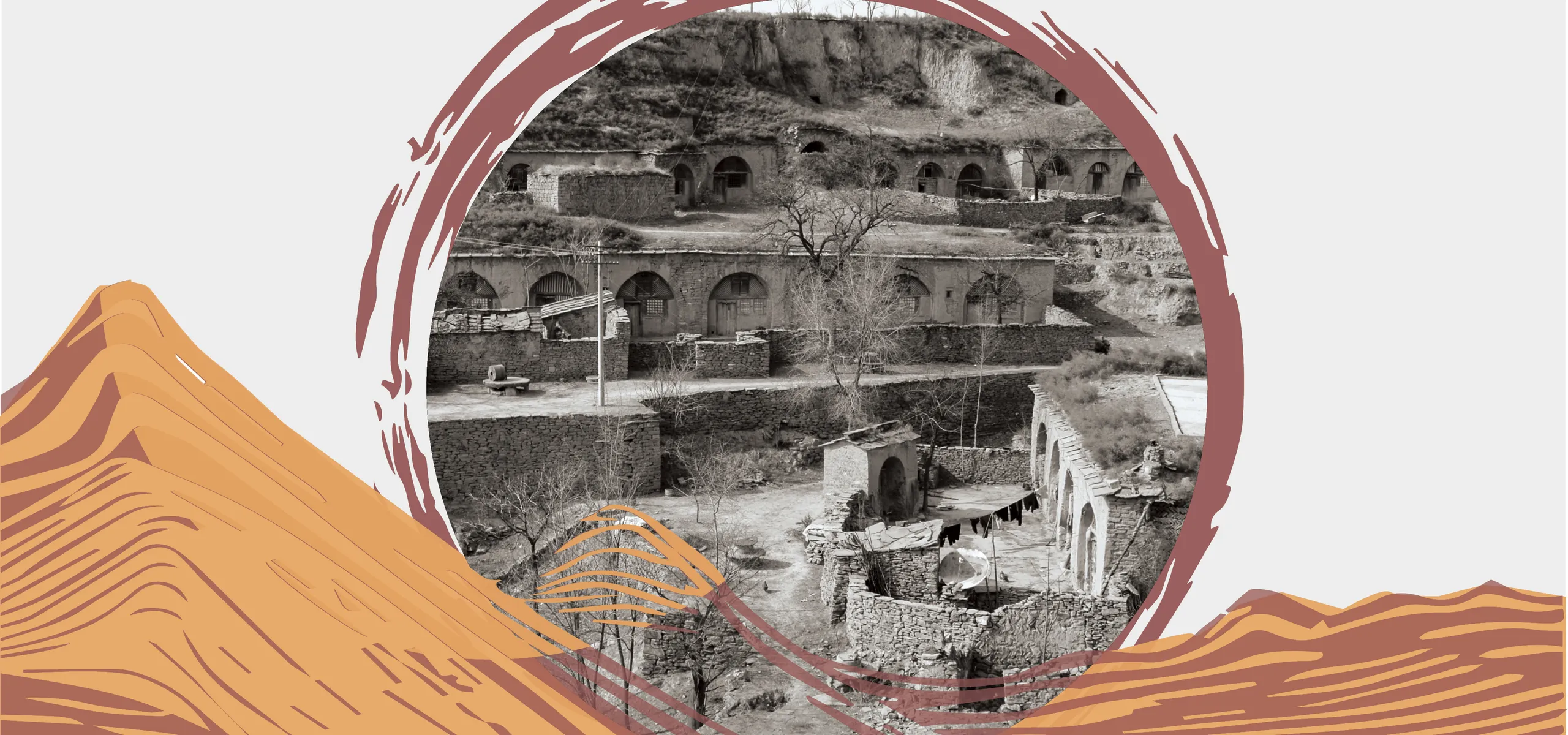

Yellow earth, big skies, tanned peasants tending to barren fields…you can guess, without looking up the synopsis of director Li Ruijun’s acclaimed new film Return to Dust (2022), that it is set in northwestern China.

The tragic love story between farmer Ma Youtie and a disabled woman called Cao Guiying, filmed in Li’s native Gansu province, was selected for the Berlin International Film Festival and made over 100 million yuan at the box office within two months of its July release (though has been abruptly taken offline at the time of writing). Despite this, it has faced accusations of pandering to viewers’ stereotypes about the Northwest.

While films and literature set in China’s northeastern provinces are typically stories of social malaise in post-industrial cities, the Northwest—usually referring to the provinces of Shaanxi, Gansu, Qinghai, the Ningxia region, and parts of Inner Mongolia—have just the opposite feel. Many well-known works set in these regions, particularly the areas mostly inhabited by Han people, present rural themes such as the harsh natural environment, strong kinship and social bonds in villages, and conservative values that shape the destinies of their characters.

Visually, these works feature familiar elements based on cultural archetypes from the most populous province, Shaanxi. “We have had a lot of early literary and artistic works that have presented an image of Shaanxi as [a place with] yellow soil, Baota Mountain in Yan’an, people wearing white turbans, a red sash, and a waist-drum, or an old peasant with a big cotton-padded jacket,” says Xi’an-based journalist and culture writer Zhang Xuefeng, a member of the Shaanxi Writers’ Association. “This puts labels on Shaanxi, and contributes to a lot of misconceptions from outsiders about the province.”

Northwestern China has had a historical association with farming—fittingly so, as the Yellow River plains stretching from today’s Shaanxi to Henan province were the origin of agrarian civilization in China in the Neolithic period. The Northwest, especially the city of Chang’an (now Xi’an), hosted the capital of various ancient dynasties, until wars with northern invaders caused the center of power to gradually migrate toward the Yangtze River in the south in the Song dynasty (960 – 1279).

In modern China, the region came into prominence in the arts after 1935, when the Communists established their power base near the city of Yan’an in the northern Shaanxi plateaus at the end of their Long March. During the 1930s and 40s, left-leaning artists and intellectuals migrated to Yan’an to experience the lives of local peasants and create works sympathetic to the cause. In 1938, they founded the Yan’an Film Troupe for the purpose of “uniting and encouraging the people, and fighting with the enemy.”

The troupe was made up of many well-known filmmakers, and produced some notable documentaries on war and the lives of local people, including Yan’an and the Eighth Route Army (a lost film from 1938) and On the Nanniwan Frontier (1943). The films served a strong political purpose, aiming to present the Communists’ closeness to peasants, who were depicted through a mix of stark poverty, oppression by feudal values, and salt-of-the-earth simplicity.

Many of the Yan’an Troupe’s films were lost in the Anti-Japanese War, and it later merged with the Jilin Film Studio in the Northeast after 1949. The Northwest lost its central position in Chinese arts until after the 1978 reforms. As its economy started lagging behind the urbanized eastern seaboard, the region retained an agricultural lifestyle and family-centered culture, which inspired writers such as Lu Yao, Chen Zhongshi, and Jia Pingwa. These writers, all from Shaanxi and all in their 30s and 40s at the time, produced several well-known works with rural themes set in their home province: most notably, Lu’s Ordinary World (1986), Chen’s White Deer Plain (1993), and Jia’s various works (many of them available in translation) tackling subjects like Shaanxi folk opera and female trafficking.

Zhang believes that these Northwestern artists were more attached to rural themes because of the long history of agriculture in the region. “Compared with the cultures in southeastern coastal areas, the Northwest has a prosperous rural civilization based on the attachment to one’s roots and clan culture,” he says. Today, the region has the lowest level of industrialization and urbanization in China, with Xi’an as the only major city, and is home to just 7 percent of the national population.

In cinema, Chen Kaige’s Yellow Earth (1984) influenced the look and tone of many films set in northwestern China in the reform period. It tells the story of a Yan’an-era soldier who visits a poor village to learn folk songs, setting off a tragic chain of events. The film owed much of its visual style to cinematography by Zhang Yimou, who was born and raised in Shaanxi and, along with Chen Kaige, was part of the “Fifth Generation” of film directors who graduated from the Beijing Film Academy (BFA) in the 80s. Zhang later directed The Story of Qiu Ju (1992), transporting the tale of a woman seeking justice against an abusive village leader from the original novel’s setting in the south-central Anhui province to Shaanxi.

Chen Kaige and Zhang Yimou were both mentored by experimental director Wu Tianming, who became head of the Xi’an Film Studio (XFS) in the 80s. Founded in Shaanxi’s capital city in 1958, the studio originally made films showing production by the workers and peasants. To modernize the studio in the reform period, Wu recruited several BFA graduates. Although not all XFS films from this period were set in the Northwest, rural themes were common in the Fifth Generation’s early works partly because of Wu’s insistence on “letting the films reflect reality and ordinary people.”

In the new millennium, the film industry turned toward marketable films with modern urban themes set in big cities such as Beijing and Shanghai, and XFS lost its prestige. Yet familiar Northwestern tropes are still present in a few recent works, such as in state broadcaster CCTV’s hit 2021 series Mining Town. Based on the true story of a group of Ningxia villagers relocated under a government anti-poverty campaign in the 1990s, the film echoed Yan’an works such as Nanniwan, with the farmers finally able to make green orchards in the barren landscape grow through hard work and guidance from the government.

By contrast, Return to Dust is a more introspective work that focuses much on the individuality and personal struggles of its protagonists, a trend that Zheng Yifei, a 30-year-old independent filmmaker from Gansu, sees in works by young independent directors from the Northwest. “The independent films…are closer to people’s lives,” he says. “It’s not about success, failure, or political achievement, but specific people, their living environments and issues they have to face.”

Zheng’s only film to date, an art-house documentary called Trashy Boy, premiered at the FIRST International Film Festival this year. It centers around a troubled young man in a small town in Gansu who finds solace in rap music, and is narrated mostly in standard Mandarin (with some rapping in Shaanxi dialect). The visuals—including an ancient drum tower, snow in the desolate streets, and snoozing shopkeepers bereft of customers—highlight how young people from the town feel trapped and struggle to find meaning in their life.

The protagonist of Trashy Boy is a friend of Zheng’s, and Zheng says his directorial choices come spontaneously from his own life experiences. “[The Northwest] is the place I’m most familiar with, and so it naturally became the setting for all of my stories, because you can only have those types of people, those lifestyles in that environment,” he says. He speculates that rural themes used to be more prominent in films from the Fifth Generation, and appealed to audiences of that era, for the same reason: “China was undergoing a transition from an agricultural society, and people of that generation had more emotional attachment to the land.”

Zhang, the writer from Shaanxi, believes artists should “tear off the membrane” of stereotypes about the province. He refers to several works from the Northwest with urban themes (or more accurately, urbanization themes), such as Chen Yan’s novels The Protagonist (2018)—which won China’s highest literary award, the Mao Dun Prize, and is being adapted for TV by Zhang Yimou—and Set the Stage (2015), which has been adapted into a CCTV drama. Both books deal with conflicts that arise when rural people move to the cities.

However, Zhang admits that on the whole, such works are not yet influential enough, nor get enough recognition from the establishment, to change the narrative, arguing Shaanxi needs “phenomenal work” to alter its image.

But Zheng, the director, doesn’t feel like movies should bear the responsibility for changing stereotypes, and is more interested in bringing multi-faceted, authentic characters to the screen. “I may have made [Trashy Boy] this time, but next, I could make a film with a rural setting,” he says. “As long as I think a place has people who deserve to have their stories told, I’ll go film them.”

Whoever the subject, he is certain that his next films will be set in the Northwest: “It is fertile soil for people with stories worth telling.”

Contributions from Hatty Liu and Siyi Chu (褚司怡)

Left in the Dust: Shaking Rural Cliches in Films on Northwest China is a story from our issue, “The Data Age.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.