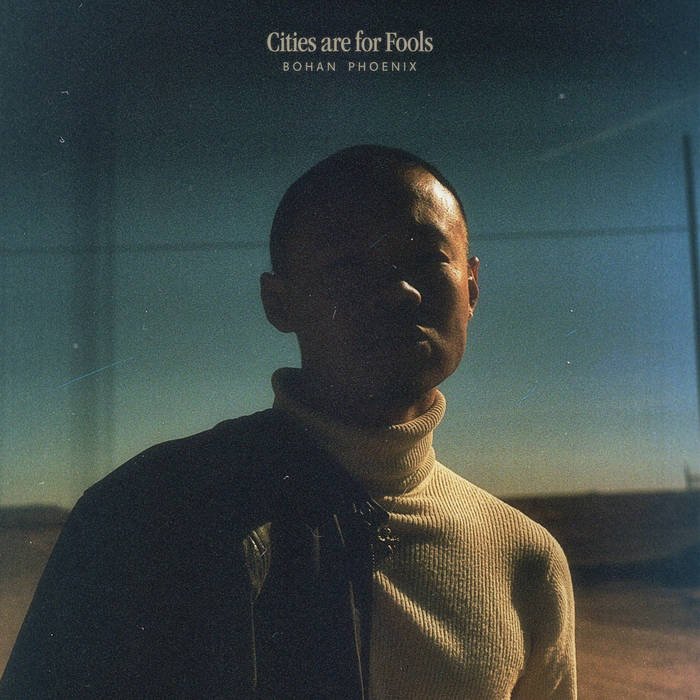

Chinese American hip hop artist Bohan Phoenix reaches beyond his “in-between identity” to craft new sounds

Effortlessly funky bass lines and guitars reverberate, weaving in and out of a jazzy brass section as Chinese American rapper Bohan Leng, who goes by the stage name Bohan Phoenix, spits a love letter to the Big Apple on “New York Made Me” in his signature straight-talking wit. The opening track of his debut album Cities Are for Fools, this is a live music-inspired ode to the city where he’s lived since 2010:

Got the fuck up out the country then I realized

What I needed was in front of me the whole time

I don’t know what I would do without these trill lights

Without these vibes I could probably kill life

A seasoned performer who has divided his time between China and the US for a large portion of his career, Leng pays homage to New York, LA, Boston, and Chengdu in his long-awaited album, a culmination of the rapper and activist’s philosophies regarding life, and how the cities he’s lived in have shaped him.

Born in China’s Hubei province, but having moved to Massachusetts at the age of 11, Leng’s body of work to date has been marked by themes of being foreign in both cultures, and the push-and-pull of finding ones’ roots while being far from home. He has previously dropped tracks such as “JALA” (2017), “FOREIGN外國人” (2016), and “OVERSEAS 海外” (2018) which fast solidified his niche as a rapper who focused on the “in-between identity,” alongside pioneers such as MC Jin, the first Chinese American rapper to be signed to a major US label, and Wang Leehom, who created his own “Chinked Out” sound fusing Chinese traditional music with hip hop elements.

But while many diaspora artist have packaged themselves as a “bridge” between cultures, Leng has made special effort to walk the talk. Besides his own music, he is known for his work in getting Chinese hip hop group Higher Brothers signed with Asian diaspora-focused music company 88rising in 2016, making the Chengdu-based foursome the first fully Chinese-speaking group of rappers to achieve critical acclaim in the US market with their fiery flows and lyrics dealing unabashedly with local topics like WeChat.

Leng’s musical journey is deeply intertwined with his personal journey of putting down roots in America. Describing himself in a Lifted Asia interview from 2021 as not being able to speak a word of English when he arrived stateside, a young Phoenix gave himself over to the beats and flow of hip hop, predominantly influenced by rapper Eminem. Instructed by his mother to watch American films to improve his English, Leng saw the film 8 Mile and resonated deeply with Eminem’s role and backstory. “For a kid just moving to the States from China, where I grew up in rural Yichang with my grandparents, I felt lost, too. I felt like an outcast...and I thought [hip hop] could give me the same confidence and the same feeling it had given [Eminem,” he said. “Before I knew it, hip hop was all that I cared about.”

It’s been over a decade since Leng started testing the waters of the hip hop scene, starting from humble beginnings as part of a duo called Hiphopaganda in 2008. He then moved on from that duo project onto solo works under different monikers such as “Phinale” before landing on his current stage name. Inspired early on by the hard-hitting rap style of Eminem and the smooth stylings of D’Angelo, Leng combined these influences with his own touch; producing bilingual chili-hot lines laid down over extravagant, dissonant trap beats which appealed in a fresh way to third culture audiences all over the world.

No matter the language I spit in the verse

I make sure I know what I’m worth

The powers preserved within all these words

Make certain I thrive on this Earth

The noun and the verbs are never rehearsed

They come to me natural as birth

– “OVERSEAS 海外”

Leng’s reverence for the genre has also made him a strong ally to the Black Lives Matter movement; notably using social media as a platform to reach out to Asian artists and collectives such as 88rising to rally support, while further exploring the ethical responsibilities of being an Asian hip hop artist profiting off Black culture. “For anybody that’s profiting off of Black culture, I would encourage them to realize that they are indebted to Black culture and should feel a responsibility to give back and uplift it…hip hop helped me find belonging as a Chinese immigrant kid growing up in America. It sustains my livelihood now. It’s allowed me to travel the world and meet amazing people, expand my worldview. I will always be grateful for that,” he said in a 2020 interview with Asian Pop Weekly.

The rapper’s vocal stance especially on the Black Lives Matter movement sparked a wider questioning of whether creatives in the Asian hip hop scene are doing enough to give back. In a 2020 piece by Variety on how Chinese rappers are contributing to Black Lives Matter, Leng called out 88rising for not contributing enough to the movement, estimating that the 60,000 US dollars the label donated toward the cause was less than a fee for a single Higher Brothers performance in China. “I’m tagging people who I know have made racks from hip-hop and can match me,” he wrote in an Instagram post to “Asian friends who make money by means of black culture,” calling on them to make donations or match his. “I see some of you donated $25 or $50 or your halfhearted copy-and-paste posts, but nah, that’s not it. You know I know how much you make.”

In an interview with APW, he suggested that those who are unable to donate can start conversations with their parents, coworkers, and peers about their biases: “Everybody can do something beyond just posting a black square with a hashtag on Instagram.”

Leng decided to move back to China between 2016 and 2019, telling Mixmag Asia in 2020 that he had understood there was a “new wave of popularity” for hip hop happening in China that he wanted to be a part of. He also made the controversial decision—for those who knew him as a fiercely independent artist and strong advocate for artistic freedom—to sign a deal with Warner Music China, one of the “big three” major label conglomerates in the country, to distribute his debut album in mid-2021. This he credits to a personal decision: a desire to obtain a business or employee visa to allow him to make more visits to his family, whom he references often in his songs. “I was born in China and besides my mom, all my family is in China,” he told APW. Ultimately, he was unable to obtain the visa, but says he would do it all over again, despite all the challenges. “I probably would sign it again, because if I could get back into China, then I was willing to do it.”

While in China, Leng worked with some of the scene’s most prolific and critically acclaimed hip hop acts such as Vava on their single “Money Game” and Xinjiang rapper Akejiang Akin on “Grandpa 爺爺,” and was even asked to join popular reality show The Rap of China, which he declined three times due to the limitations the contract would have put on the shows he played at or even how he presented himself. “Even when I was talking with the show’s producers, they were like, ‘Oh, you can’t wear your bandana.’ Or, ‘You have to speak more Chinese.’ If I was younger, like 18 or 19, I would have been on that show because, in my mind, the only thing would have mattered to me was the dollar signs,” he told Mixmag Asia. “But I think because I was lucky enough to have spent time in New York and experienced a lot before moving to China, I knew I couldn’t do something like that and sleep well at night—no matter how much money it was going to put in my pocket.”

Back in the US, he has reflected on the understanding he developed of the nuances and differences that exist between the US and Chinese hip hop industries. ”There’s still a very big idol-chasing culture aspect toward the hip hop scene in China, partly due to the variety of hip hop reality shows and competitions. So that in itself is very different to the United States where a more organic route is encouraged or celebrated. But that might be smoke and mirrors as well,” Leng tells TWOC. “But I do think both scenes right now are extremely exciting, because we’re on the cusp of a lot of changes culturally, technology wise…I think right now it’s a time to really dive in and have fun and not really hold yourself to any limitations or in a box.”

An honest homage to the big cities that have hosted his dreams; from New York to Chengdu; from Boston to LA; from the listening experience to the process of the album’s creation and negotiation of its ownership we see Phoenix at his most vulnerable, loose, and spontaneous. Moving away from the iconic theme of “foreignness” that he’s built his brand on, Phoenix nevertheless continues to find different ways to exert his representation and share his unique perspective in a constantly changing environment. While “home” is often a complex concept for someone like him, it seems that at least on this groovy live-inspired record, he sounds more at home than we’ve ever witnessed before.

Written by Jocelle Koh