From developing film in the shower in the 80s, to assisting in one of China’s earliest TV documentaries, a judge from our “Most China” photo contest reflects on what humanistic photography means to him

As TWOC’s “Most China” photo contest approaches its deadline, we’re inviting photographers and photojournalists on our judging panel to share their stories, the inspiration behind their work, and any advice they have for readers who want to start shooting. Today we hear from Huang Ruide, a Guangdong-based folk culture photographer who was part of a wave of student photography enthusiasts in the 1980s, and learned on the job as an assistant on in one of China’s earliest TV documentary projects.

There is still time to submit to the contest! Please read the submission guidelines and send your work to marketing@theworldofchinese.com by August 31, 2022, for a chance to win prizes and see your work in print.

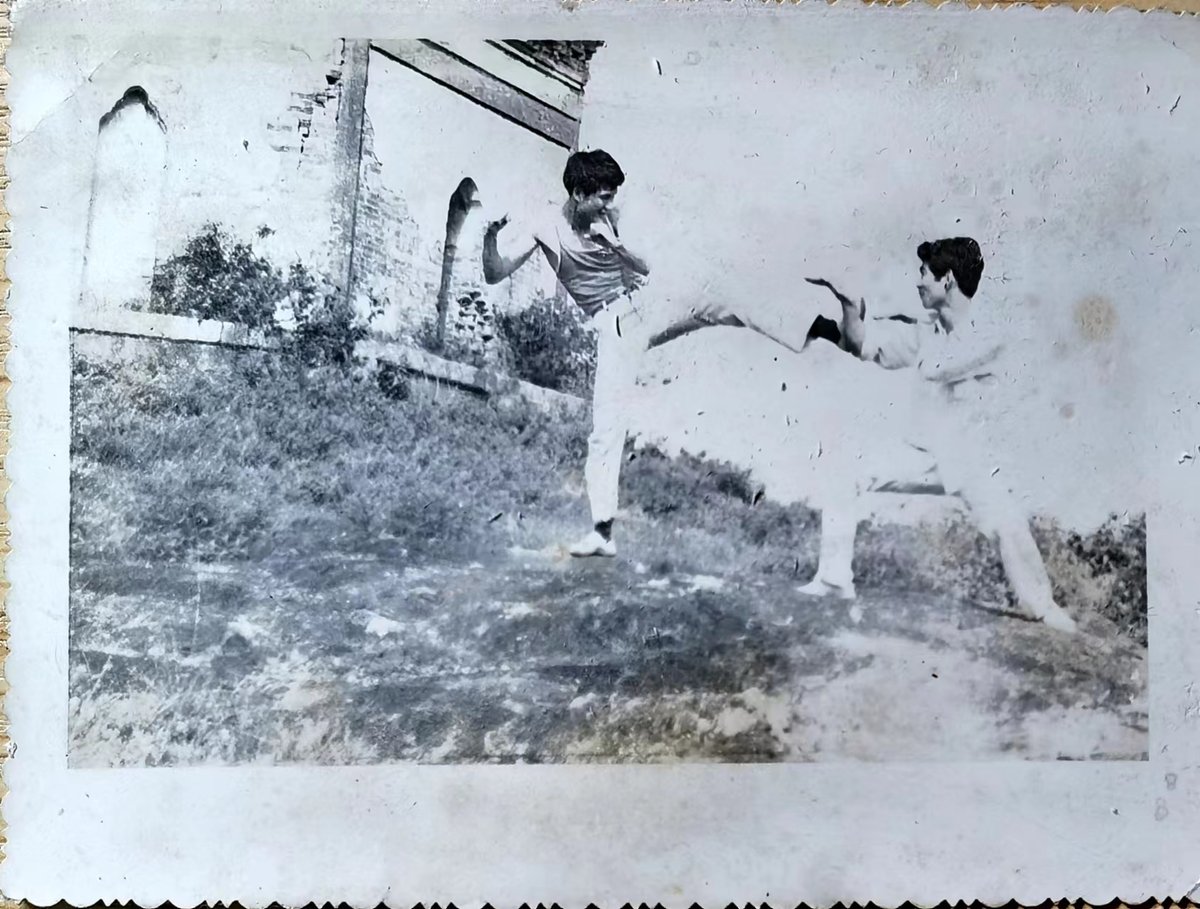

I was part of the third class of college students in China to go to university after the national college entrance exams (gaokao) were resumed in 1977 following the Cultural Revolution. My classmates came from all over the country, and we were liberal arts majors with lively spirits. A lot of us discovered in our third year that we were interested in photography, and a few kids from well-off families had cameras, so we formed a loose alliance around this interest.

My classmates from Baoding found a few rolls of film, while some students from Shantou bought a few leftover reams of photographic paper. The handier students among us built some printing machines out of old wooden boxes. Everyone raised funds to buy consumables such as developing and correction fluid; occasionally we also borrowed them from the Communist Youth League Committee. When my course load permitted, I ventured out on the weekends to take pictures. At night, I used a quilt to seal off the shower stalls down the corridor and turn the space into a darkroom.

For the next two years, until my graduation, I practiced the whole gamut of technical processes in film photography; as for my aesthetic sense, I relied on my own liberal arts education. These were, in fact, the origins of my exposure to photography. Though I had no achievements to boast about, I did immerse myself deep in the medium in the hopes that something would stick.

Upon graduation, I was assigned my first job. It was in a water conservation unit for the Pearl River. At that time, the whole country was avidly watching the 1983 CCTV documentary series Story of the Yangtze River (《话说长江》), which documented the lives of ordinary people around the Yangtze Basin as they emerged from a decade of the Cultural Revolution and embraced reform. I was certainly no exception; I now wonder whether the series stirred in me a certain restlessness. Guangdong TV decided to jump on the bandwagon and shoot their own series of documentaries on the Pearl River Delta in cooperation with my work unit, so I ended up assisting in the filming. Now, if a work unit agreed to cooperate with the project, they’d of course want to send one of their own people along for the ride. That person was me.

My work unit provided me with a full set of photographic equipment and a convenient expense account, and I was tasked with following the TV presenter, ready to start shooting at his signal. As I stood behind him and copied what he did, I gradually came to understand what an exquisitely challenging medium filming was. Prior to shooting, the presenter always did some preliminary, in-depth desk work. Wherever we went, he knew where and what to shoot, as well as any unconventional angles we could attempt, beyond the usual takes.

For instance, when we had to shoot the Lijiang River, he decided to climb to the top of the highest surrounding mountain. However, at the time there was no clear hiking path, nor did we have any climbing equipment to assist us. The presenter stepped on a protruding rock at the top of the mountain with a camera weighing a few dozen pounds on his shoulders, when the rock suddenly began to shake, and his body shaking with it. There was a sheer drop under the rock; he was just like an illustration of flying apsaras of Buddhist mythology. I was crouching behind him as usual, and reflexively I stretched out my hand in an attempt to help, and began to lose my own balance. We almost both became Buddhist spirits that day.

In the end, we made it down the mountain without incident, and bounced back up to rush and shoot Elephant Trunk Hill, laughing heartily as the initial shock subsided. As we stood at the shore at dusk, the presenter decided he was not satisfied with our angle, so we jumped into the River Li. We emerged from the cold water with our noses and lips blue, and our bodies pale.

Plunging from one thrilling adventure to the next, the presenter was actually exploring a unique perspective on life, looking for extraordinary shooting angles that were out of reach for ordinary people. It was a good approach that inspired me to keep two factors in mind when picking up my camera—first I decided on the subject, and second, the shooting angle. Of course, I am not condoning reckless exploration. There is more to life than just photography and videography.

In the course of this job assignment, I traveled to Hainan on a business trip and heard from the locals that the house of Nan Batian, the feudal despot in Xie Jin’s feature film The Red Detachment of Women, still stood in Lingshui county. Years later, now in my capacity as a reporter for a renowned magazine, I made a special trip to Nan Batian’s former residence for an interview. A round of extensive, in-depth investigations proved that the facts differed greatly from the rumors. In 1961, Xie Jin settled on the old manor of Zhang Hongyou (张鸿猷), a rather benevolent local landowner and educator, as the location of fictional character Nan Batian’s manor. The Red Detachment of Women was released a year later to the great pride of the locals.

However, when the Cultural Revolution swept in, fiction replaced reality and Zhang Hongyou’s noble memory was replaced—and tarnished—by that of the infamous Nan Batian. If you weren’t really a despot, why would the film crew choose your house for the movie? So the masses reasoned. An enraged mob vowed to expose to the public the tunnel through which the villain had fled in the movie, so all the floor tiles and even some walls of the Zhang manor were dug up. Of course, they couldn’t find what didn’t exist, so the furious masses drove Zhang’s descendants away from their home and into a storm of misfortune—they were criticized in struggle sessions, restricted in their employment opportunities, and even banned from joining the Party.

The story sounded almost too extraordinary to be true; as a Chinese saying goes, “seeing is believing,” so perhaps that’s why the masses were unswayed by Zhang’s words. Fortunately, I was able to gather visual proof of the facts with my camera, taking photographs of the Zhang clan and their family home. Once my work was published, it elicited a strong response from readers and other journalists. The Zhang family was also able to use this opportunity to plead their case with the county authorities and eventually rehabilitate their name.

This incident helped me realize that “pictures”—in any medium—play an auxiliary yet important role alongside words. The experience as a whole also highlighted to me the significance of humanistic photography. Mountains may remain unchanged for thousands of years, but human life is full of ups and downs. If you want to understand more about society and life, bring a camera!

I began to study the classic works of humanistic photography, both in China and abroad. The first photo album I ever bought, The Photography of Henri Cartier-Bresson, was published in 1988. However, I ended up going on a decade-long hiatus from photography due to various unexpected reasons. Then one day a new friend came across a few photos I’d snapped with a point-and-shoot camera and asked me if I was a photography enthusiast. I denied this, only for my friend to turn around and send me a Nikon D90 camera. The gift came with the following words: “Wouldn’t it be a waste of your talent if you were to abandon photography?”

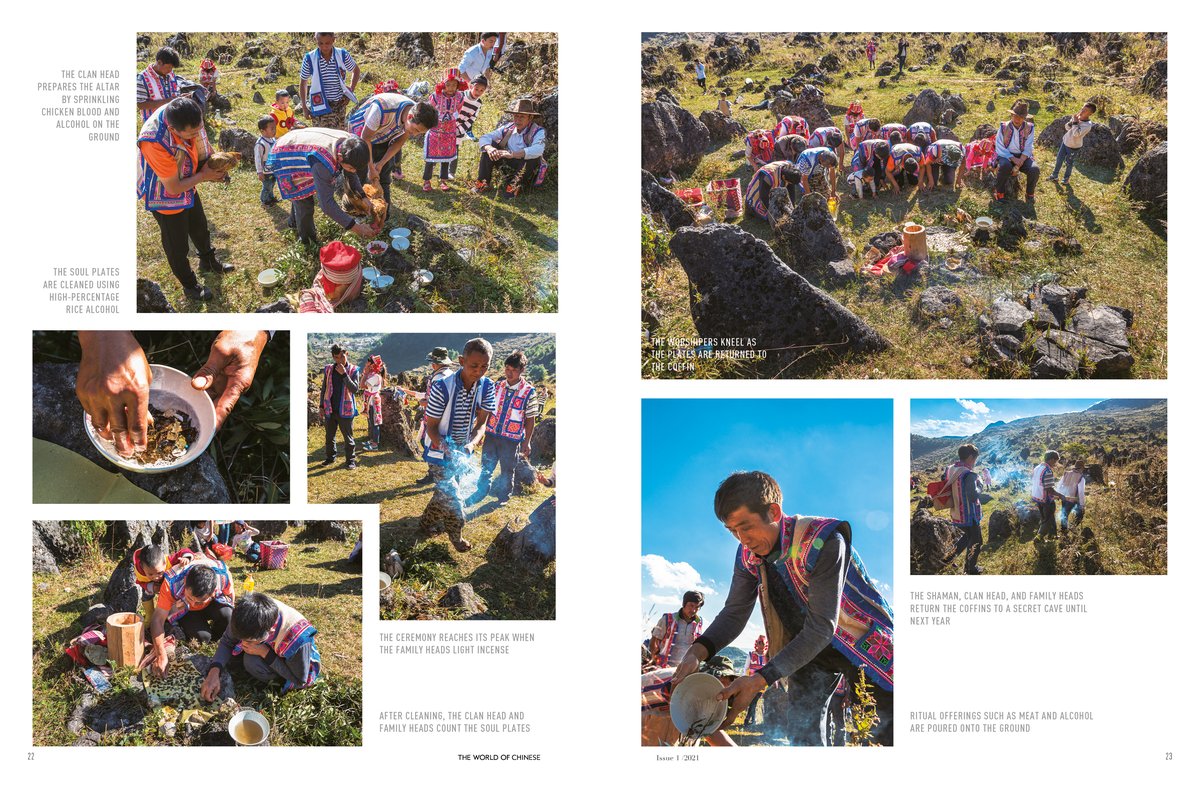

This made me feel ashamed. I could only play catch-up hurriedly, and thus I fell into a photography frenzy. In order to regain my skills and simultaneously update my knowledge, I carried my camera with me and plunged into my “subjects” every day after clocking out of my job, on weekends, and holidays. I once again devoted myself to humanistic photography, with a particular focus on folk customs and traditional skills in rural areas. Digital photography has granted hobbyists a low-cost way to snap indiscriminately. At the height of my craze, I would take over 10,000 photos a week, relying on repetition to gradually hone my skills. This went on until someone told me one day: “You’ve become one with your machine.” Another decade had flashed by at that point.

In the past 10 years, I’ve had a wealth of interesting experiences that only made me fall deeper in love with humanistic photography. If you ask me if I’ve learned anything about photography, the answer is of course yes; but whether it’s of any value to the reader is up to them to decide:

- Authenticity is the essence of humanistic photography. It is the record of reality and of history. Therefore, falsification is strictly forbidden. Should you, at the start of your journey into photography, have been misled by some teachers into taking posed or falsified photos, then you should regard the works you produced as a purely technical exercise. Once you start creating images independently, you should return immediately to authenticity. It doesn’t matter whether you need to shoot one, 10, or several hundred times; you’ll eventually get it right.

- Strive to find unusual themes and unconventional angles, if you want your works to have an impact on the viewer, rather than follow the crowd. A curious nature is a must for good photography. Even if you are setting foot in a well-trodden area, try to find unique angles that will make your viewpoint stand out.

- Do your utmost to capture the emotions and demeanor of your subjects at a particular moment. At the end of the day, human beings are animals with thoughts and emotions—sometimes hidden in the heart, sometimes overflowing on the surface. Showing people’s spirit and emotions is what makes them come alive as real humans with thoughts and feelings.

- The value of photography lies in “culture,” and this is not a value that is narrowly defined. Our understanding of culture will only grow increasingly wider as we observe our societies, read books, contemplate the classics, and engage with what we see and hear from a cultural perspective. Faced with a scene to shoot, you should quickly ascertain what’s culturally valuable and how to incorporate it into your work. If you plan your shoots this way, your work will immediately stand out among the rest.

- Photography is a never-ending progress: shoot and repeat. To improve, you need constant practice and pursuit. While you practice, you must not be afraid to think. You must not always confine your expression to a single image, but organize your thought process in terms of series of images, and strive to make each shot better than the last.

Cover image: Villagers gathering to watch a public performance in the Chaoshan region of Guangdong, a traditional part of China where seniority matters when it comes to seating arrangements in crowds (Huang Ruide)

Huang Ruide is a Guangzhou-based photographer who is a long-term collaborator with TWOC. He is also the inspiration and one of the judges behind TWOC’s “Most China” photo contest, which is accepting submissions until August 31, 2022. Enter your photos of China for a chance to obtain feedback from our professional judging panel, plus cash prizes and opportunities to see your work in print!