How a Chinese community of migrant workers and entrepreneurs put down roots in the Spanish capital of Madrid

“Even now, in our rural exodus away from China to work in Europe, acquaintances remain crucial. We always choose a place where our connections will help us settle down, find a job, earn money, and eventually obtain a permanent residence permit."

Taiping is a small village with less than 3,000 people located in eastern Shandong province, at the junction of two cities and three counties. Over the past two decades, more than 200 from people here have migrated abroad to work in countries such as South Korea, Japan, Malaysia, Singapore, the United Kingdom, and Spain. This is far from exceptional in our small, impoverished county, where incomplete statistics point to approximately 200,000 people out of an estimated 1.1 million total population having migrated to seek work abroad.

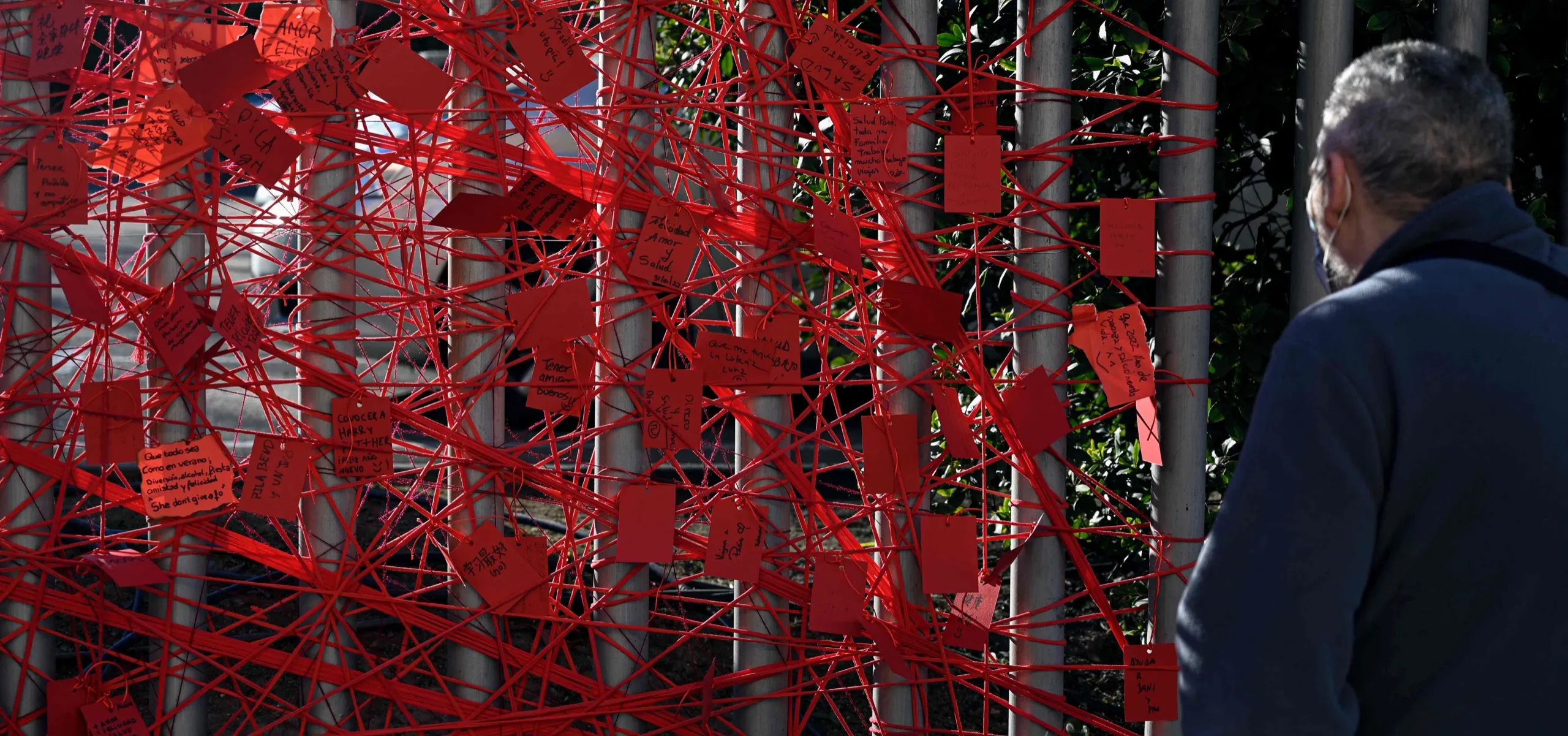

This story begins on February 15, 2019—the 11th day of the first month of the lunar calendar. Uncle Fu, who’s been back home from Spain for a visit for almost a month now, is struggling with the cold weather of his hometown. He is sitting in front of the fire, smiling as he scrolls down his friends’ WeChat Moments, saying, "Look at them marching in protest.”

At that time, hundreds of Chinese citizens were staging a demonstration on the streets of Madrid, waving flags from both countries to protest against the freezing of their accounts by BBVA, Spain's second-largest bank. To the eyes of the Chinese community, this measure was rooted in racial discrimination. Media focused on the bank’s branch in Usera, the district with the largest concentration of the Chinese diaspora in Spain. This is also where Uncle Fu often did most of his bank transactions. "Good thing I returned a month earlier. Had I delayed until after the New Year holidays, I probably couldn't even withdraw money to pay for the trip.”

Uncle Fu is 55, and this year marked the 15th anniversary of his arrival in Spain. Despite his long stay in the Spanish capital, he makes it clear that Madrid never quite felt like home; deep down, he always looked forward to returning to his birthplace.

From Taiping to Barcelona

The story of Uncle Fu’s migration started in 2004, when he was a 40-year-old electrician in Taiping with one clear fixation—leaving to work abroad. In his own recollection: “I’d had my fill of long, bitter days that melt into years." For over a decade, Uncle Fu had been the only electrician in Taiping, where he’d dealt with wires, poles, and light bulbs galore. Every day, he made his rounds fully equipped with a safety helmet, locks, and a string of electropobes around his waist. A pair of large steel-tied shoes hung on his shoulders, ready to assist him in climbing telephone poles.

He was a fast climber—the fastest in the entire county, as his peers from nearby villages could attest after get-togethers where three rounds of drinking led an impromptu climbing competition. Uncle Fu came out on top.

Power outages were routine in Taiping. Summer nights saw the streets of Taiping shrouded in silence as soon as the electricity was cut off. The locals carried their folding stools to the streets seeking the shade, brewing their frustration in the heat.

However, their anger toward Uncle Fu was misplaced. The circuit in the village was old, and the transformer at the south end of town could only help so much. Despite the abuse that was hurled at him occasionally, Uncle Fu had to keep working. Safety was his main concern after witnessing the accident that befell a fellow electrician in a neighboring village, who was struck by high-voltage electricity. Though the man was rescued, both his legs had to be amputated, so he had to open a canteen where he could be seen wearing his prostheses. At the end of the day, Uncle Fu was supporting his whole family of four on a meager monthly wage of 300 yuan. It was barely enough to buy a couple of sacks of chemical fertilizers from the cooperative store that had been built in the south area of town back in the 1970s; it couldn’t even cover half a year of tuition and miscellaneous fees for the local primary school.

Villagers of Uncle Fu’s age rarely stayed in Taiping. Most of them banked on their ability to seek work at the nearest urban hub—Qingdao, more than 200 kilometers away, but with plenty of construction sites, a shipping dock, and the manufacturing and service industries that took in school dropouts born in the 1980s. Qingdao was not necessarily remote, but returnees only made it back home thrice a year: once during the Lunar New Year, once for wheat harvest season, and once for the autumn harvest period. Uncle Fu had his sights set much farther; he wanted to migrate to Europe. "There was this local girl, Xiao Rong; she left for South Korea. At that time, she was the first person in our village who went abroad to work. A woman, no less. If she could venture to a foreign country on her own, what was stopping us men?"

At the time, some folks in our home county had gone to Spain, working odd jobs in Barcelona and Valencia. News of their endeavors trickled down to us over the years. Uncle Fu drew inspiration from them and chose his destination rather deliberately. "Back then, my immediate choice was based on my acquaintances. It still works like that. We always choose a place where we have connections that help us settle down, find a job, earn money, and eventually obtain a permanent residence permit.”

Uncle Fu sold his place and car, borrowed money, and allotted hundreds of thousands in cash to pay intermediaries along his journey. Eventually, he was able to board a flight to Barcelona in May 2004. He did not go alone. Mr Yang, his elementary school classmate, was his travel companion.

First jobs

Following in the typical steps of his fellow countrymen in Spain, Uncle Fu started working at a Chinese restaurant as soon as he stepped foot in Barcelona. The place was run by a native of Qingtian county, Zhejiang Province, and a local contact had made arrangements for Uncle Fu to wash dishes there. Mr Yang, who was now living in Valencia, was hired on similar terms.

To this day, Uncle Fu still remembers his restaurant days vividly. His daily shift stretched from 11:30 a.m. to 4:30 p.m., with a break before he went back into the kitchen at 7:30 p.m. He stayed there until 1 a.m. Uncle Fu made a monthly salary of 400 euros. In his own words now, "Northerners migrating to Spain owe a lot to those folks from the south that arrived there first, particularly people from Qingtian. They were pioneers, and by the time we came here they provided most of our jobs.”

Uncle Fu thought washing dishes in Spain was easier than farm work at home. There were regular hours, and the work was easy from Monday to Friday, only getting somewhat busier on the weekend. "It was kinda like being a civil servant." He could also take a day off each week.

Of course, money was only part of the picture for Uncle Fu, for whom gaining legal status and social recognition was the true sign of a worker's success. However, just how attainable were those goals for an ordinary migrant worker from rural China? Spanish law states that foreigners are to complete a minimum of three years of registered residence at an appropriate address. Once you’ve fulfilled this requirement, you can apply for Spanish residence under “social integration,” such as family ties, entrepreneurship, or employment. The caveat here is that your employer needs to act as a guarantor, ensuring that you will have a job and subsequent income during your time in Spain.

Uncle Fu came to the realization that he would have to depend on his job to get permanent residence in Spain. It was around this time that his niece Da Fei, his eldest brother’s daughter, joined him in Barcelona. “I picked her up when she arrived in the city, an 18-year-old girl who’d just graduated from middle school,” says Uncle Fu. “Since she was still so young, I figured I should help her apply for a residence permit first. I thought it was worth the risk, even if I was eventually caught and booted back to China." This is how Uncle Fu’s priorities shifted shortly after his arrival in Spain.

***

Uncle Fu was indebted to his boss at the restaurant for Da Fei’s first temporary residence permit. “I had to repay him, since he’d helped me a lot. I made a promise to pay him 140,000 yuan—about 5,000 more than the price at that time. I paid 60,000, and Da Fei and I worked at his restaurant to pay the remaining 80,000.”

For the next three years, Uncle Fu and his niece spent their days washing dishes in the restaurant, saving money and waiting for the moment they could apply for permanent residency. Da Fei’s monthly wages were 180 euros, and Uncle Fu told her this was their reality for the foreseeable future. “We have no choice; this is all the boss is paying us.”

Later, Uncle Fu learned that a relative’s acquaintance was working at a clothing factory in Valencia, making 2,400 euros every month. This success story stirred Uncle Fu’s envy, and he immediately reached out to this person to find out more. Since he couldn’t leave his job at the Chinese restaurant, he used his one day off each week to go to Valencia and learn the ropes at the clothing factory. In the early morning, he’d take the train for a lengthy journey. At the garment factory, he worked until 3 a.m. the next day, when he’d hop on the train back to his dish-washing duties in Barcelona. “I went for a total of 15 weeks, and I never saw a cent from that [acquaintance]. At my most exhausted, my legs would be shaking, and I’d fall asleep in the train.”

June 2007 marked the third anniversary of Uncle Fu’s arrival in Spain and his teaming with Da Fei, whose new work permit finally came through. This step meant she was finally no longer relegated to the sink in the dark kitchen—she now had the right to choose a job freely. For Uncle Fu, it also he was also finally free to follow his own dreams.

Though nobody understands why he didn’t apply for his own permanent residence permit first, Uncle Fu’s explanation is simple—he saw no difference between doing it for Da Fei or for himself. "Family bonds will always prevail over anything else. Familial love and relationships are more important than a permit." Interestingly, adhering to such values, outdated as they were, provided Uncle Fu with a magic weapon of sorts to put down root in Spain.

***

After his niece switched to a new job, so did Uncle Fu immediately. He quickly joined the ranks of a local clothing factory, working some 15 or 16 hours a day for three months for a monthly wage that was still modest. Thus, Uncle Fu decided to relocate to Valencia to work as a chef in a restaurant where Mr. Yang worked part-time. His former travel companion had ascended to the position of sous-chef from his original job as a dishwasher, and was now raking in over 2,000 euros a month. Over the next decade, Uncle Fu and Mr Yang became the star characters populating the stories of migrants abroad in their native Taiping. However, Uncle Fu wasn’t really cut out to be a chef. "The boss would ask me to make whatever dish, and all I could think was, back home I couldn’t even make instant noodles." Uncle Fu had no option but to leave again. "At that time, I only had 20 euros left in my pocket. I was wandering the streets of Valencia, lost in my thoughts. How could I find a way back home? What was my life going to be like? I just kept racking my brains and crying."

Uncle Fu had hoped for a fresh start and a chance to finally make money, but neither had come to fruition, and he felt a little depressed. Mr. Yang, his elementary school classmate, was already making a small fortune and well on his way to successfully applying for a residence permit. That had always been Uncle Fu’s goal. Mr. Yang, on the other hand, just wanted to make enough money to return to China.

In the most difficult periods of his life, Uncle Fu's skills as an electrician helped him. Several people he knew from back home had since come to work in Spain, and so Uncle Fu hurriedly left Valencia to return to Barcelona and be with a relative who’d gotten into the business of repairing refrigerators. The pair hit it off, and Uncle Fu wanted to apply for a permanent residence permit now that he had a job. However, his lawyer said he still needed to wait. Uncle Fu asked around and eventually learned that it was easier to apply from Madrid, so he considered leaving again. Unlike Mr. Yang, Uncle Fu only cared about becoming a legal resident. In his own words, “I owed it to myself.”

Starting a business

At that point, Uncle Fu had been living in Spain for nearly four years, changing jobs just as many times. On March 25, 2008, he embarked on the journey from Barcelona to Madrid, his toolkit in tow. Arriving in the Spanish capital, he stayed first in a restaurant where an acquaintance from Taiping was working. Uncle Fu recalls it was raining heavily that day. "Like the sprinklers in our village, it was pouring from the sky."

Uncle Fu sat in the restaurant and looked out the window, riddled with anxiety. The relative he’d started a business with back in Barcelona had scolded him on the phone: "I told you not to go!" He was in no shortage of reasons to feel anxious. This was his very first day on business, and he was yet to find any work, let alone repair a single refrigerator or air conditioner unit.

At a certain point, he’d been tempted to bin all his repair tools and go back to washing dishes, his last resort in his despair: "After three years at the sink, I’d developed a fondness for washing dishes. Whenever I tried to do anything else and it tanked, I always felt compelled to just go back to the restaurant to wash dishes."

Back home, Uncle Fu’s wife had also voiced her complaints when she learned that business was not thriving. In the past four years, Uncle Fu had only managed to send a meagre 100 euros home each year, barely over 1,000 yuan. He had yet to accomplish anything apart from helping his niece get a residence permit, in stark comparison with acquaintances such as his old neighbor Brother Shu, who’d migrated to Spain later than Uncle Fu but was sending 1,500 euros to his family every month—nearly 20,000 yuan. Mr. Yang was also sending a monthly total of 2,000 euros home.

It goes without saying that this amount of money made a big difference the average rural Chinese rural family in 2008. Aunt Fu’s patience was running out. After the rainy season had passed, Uncle Fu bit the bullet and advertised his repair services far and wide. To his amazement, customers started flocking to him. He only found out much later that his newly found luck came from the tragic passing of a repairman from Taiwan who had been serving the Chinese community in Madrid. As he unwittingly filled in the vacancy left by his ill-fated predecessor, Uncle Fu lured customers in with a bold offer: If they did not trust his skills, they could wait two months to pay for his services; should any problem arise with his repairs within three months, he’d make additional repairs.

For a whole year after the start of his business, Uncle Fu was like a tractor at full power, schlepping his equipment through the streets and alleys of the Chinese community in Madrid. His steady occupation seemed to be a reward for his four years of hardship in Spain. Business was thriving, so much so that he kept himself busy until the Lunar New Year's Eve in 2009. "That day, I came back from work at midnight, and Brother Shu had already prepared everything for the celebration." Uncle Fu recalls with a smile, "At that time, I just thought I’d finally got my lucky break."

On August 4, 2008, Uncle Fu’s permanent residence permit had finally come through. Uncle Fu treated his local friends to a celebratory feast in a Chinese restaurant, fully aware of the significance of his achievement: “There’s no sense of security whatsoever without a residence permit. Without it, you’re at the mercy of whatever bully that comes your way. Many people cry when they get their permit. We’ve gone through so much in our time in Spain." That year, Uncle Fu saved more than 10,000 euros. On the fourth day of the first lunar month in 2009, after working in Spain for nearly five years, Uncle Fu and Mr. Yang decided to go back to Taiping Village to visit their families.

***

Migrating abroad had become a common practice in Taiping Village in 2009. Xiao Rong, one of the first girls to migrate from our village, had given birth to her second child in South Korea; Xiao Yan, another female migrant, had also married a promising young man in South Korea. Cousin He’s wife had migrated to Japan, though this later proved to be the first crack in their marriage. Having waited seven years for a chance, Da Quan, an old neighbor, had finally been able to go work in Oxford, England…and many more were getting ready to depart. Uncle Fu stayed in the village for only half a month before hurriedly returning to Spain to resume his business. Mr. Yang stayed in Taiping. Nobody knows why he gave up his career as a chef in Spain. Perhaps he thought he’d made enough to return home and enjoy a peaceful family life.

A piece of Shandong in Usera

Upon his lonely return to Madrid, it took Uncle Fu an additional four years to finally gain a strong foothold. Usera, his district of residence at the time, is home to the largest bastion of the Chinese diaspora in Spain. A community of more than 30,000 people operates all sorts of businesses there: nearly 20 supermarkets and over 50 Chinese restaurants, as well as several Chinese schools and law firms.

However, Uncle Fu was no longer satisfied with his whereabouts.

In 2010, Uncle Fu bought his first pickup truck in Spain for 15,000 euros. Thus, he expanded his network of customers to include Chinese communities in a radius of 200 kilometers. Afterward, he also started welcoming the migrant workers hailing from Shandong at the Adolfo Suárez Madrid-Barajas Airport. Uncle Fu took them to the Usera district and allowed those who came from his birthplace to stay and eat at his place while he helped them find a job.

"From 2009 to the present, it’s been no less than 200 people." For this group of fellow countrymen and women, a close-knit community proved to be a good remedy against loneliness and homesickness. In 2013, Uncle Fu went home to Taiping Village from Madrid. This was his second visit home in nearly 10 years. Now, with his own business circle in Madrid, he had a goal in mind: bringing his wife and children to Spain.

At first, Aunt Fu refused. She was a 48-year-old rural woman who had never set foot in a city, so her discomfort at this sudden move to a foreign, unfamiliar country in her middle-age was apparent. Still, Uncle Fu prevailed. In the winter of 2013, I drove Uncle Fu’s family of three to Beijing International Airport. At the time, I was still a graduate student in Beijing, and I was joined by a couple of other Taiping villagers, Brother Hao Ge and Hao Hao, who were then running a restaurant in the city. On our way to the airport, Uncle Fu's 14-year-old son Xiao Fei was excited. He’d heard that Chinese schools in Madrid had far easier courses than schools in China. However, Aunt Fu looked worried. Her giddiness when she’d visited the Forbidden City and the Chairman Mao Memorial Hall was now gone. She took the boarding pass in her shaking hands and turned back to bid a tearful farewell to us. She talked as if she’d never return to Taiping village again.

A week after Uncle Fu's family arrived in Madrid, I had the chance to video chat with them and caught a glimpse of Aunt Fu. The cheerful look on her face acted as a foil to her gloominess barely a week ago. She even encouraged me to pay my first visit to Madrid: "You should come too, there are Chinese people everywhere!" It was evident that Aunt Fu had quickly adapted to her brand new life. In this new land, she would cook for her family before going for a walk in the park after dinner, followed by some square dancing with a crowd of fellow Chinese aunties. Family members kept trickling in; in the spring and autumn of 2014, Uncle Fu's daughter and son-in-law's family also arrived in Madrid, followed by his nephew Xiao Xie and niece Xiao Feng. A year after arriving in Madrid, his daughter and son-in-law welcomed a healthy, chubby baby boy to the family. Uncle Fu had just turned 50 years old and was very excited to hold his grandson in distant Spain.

Later, Uncle Fu confessed to me that he’d never dreamed he’d be able to bring his wife and children to Spain. Sure, he’d thought he could move abroad, work there, make some money. But being able to live with his family in Spain had been an unexpected bonus.

News that Uncle Fu had settled down in Spain with his wife and kid made the rounds in their village. Mr. Yang, now settled back home for four years, was growing anxious again. That year, his wife had left to work in South Korea, and their daughter had tied the knot. Mr. Yang was home alone with his son, who was now also contemplating marriage. Weddings and home-ownership were huge financial hurdles for youth in Taiping Village. Rumor had it that Aunt Yang have moved to South Korea because she wanted to earn money for their son’s marriage.

In 2017, Mr. Yang’s wife came back from South Korea. With the whole family chipping in, they were finally able to secure an apartment in town for their son. The monthly payment for the property ascended to over 3,000 yuan and stirred up trouble between Mr. Yang and his wife. He’d wanted to build a house with a yard for their son in the village, while she had been adamant that they needed to set their sights higher to buy an apartment in town.

Meanwhile, 2017 was also a fruitful year for Uncle Fu in terms of real estate. He bought his own house in Madrid—a large property with a yard measuring 188 square meters, for a total price of 180,000 euros. This was nothing short of a dream come true for a Chinese rural migrant. Once renovations had been completed, the family of eight moved in: Uncle and Aunt Fu and their son, their daughter and son-in-law with their grandson in tow, their nephew Xiao Xie and niece Xiao Feng. When they sat down to make and eat dumplings on traditional holidays, their table held almost 20 people.

Homecoming

As early as the second half of 2018, Uncle Fu’s 89-year-old father told everyone that his son, daughter-in-law, and grandson were coming home from Spain to celebrate the New Year. In January 2019, Uncle Fu did indeed return home. In the past two years, he’d teamed up with his son Xiao Fei to further expand his home appliance repair business. Uncle Fu decided to make the most of his return by having his son attend a technical school in Jinan, in the hopes that his gained knowledge would prove useful for their business in Madrid.

In addition, Uncle Fu wanted to buy two houses in his home county. Nowadays, the price of housing there has skyrocketed to 7,000 yuan per square meter. While such a figure was astronomical for the average villager, this was a no-brainer for Uncle Fu, who was now easily making a million yuan in Spain every year.

Uncle Fu had planned to wait for a decade to save some 10 million yuan with his son in Madrid before returning with Aunt Fu to their hometown to enjoy their later years there. His real estate plans back home were meant to provide two different houses, one for them and one for their son. Being able to afford an apartment in town was the ultimate goal of any villager, and not everyone enjoyed Uncle Fu’s circumstances. In August 2018, at the age of 56, Mr. Yang returned to Madrid amid rumors that he’d been forced to do so by the constant nagging of his son and daughter-in law, who’d been unable to repay the mortgage on their apartment.

After arriving in Madrid, Mr. Yang settled in with his cousin Jie and resumed his former occupation as a restaurant chef. However, he grew unusually taciturn barely a month after his arrival, eventually turning to mumbling to himself. Cousin Jie later confided in me that Mr. Yang would often voice his dejection during that time. Nobody knew the reasons behind this sudden turn. Then, on November 2, 2018, Cousin Jie got an unexpected call from Mr. Yang: "I'm done with work, I’m leaving. You’ll find out later.”

That very afternoon, someone found the body of a middle-aged Asian male in a park in Usera, still holding a fruit knife in his right hand. A long, deep cut stretched down the man’s left wrist. Though there was a hospital just a few hundred meters away from the park, the man showed no vital signs upon discovery. The following night, Cousin Jie got a new call, this time from the police. Officers informed Cousin Jie that his number was among the frequent contacts in the mobile phone that had been found next to the corpse in the park. The deceased was, of course, Mr. Yang. A visibly upset Cousin Jie immediately called Uncle Fu in tears, informing him of Mr. Yang’s death. Uncle Fu was the first to arrive at Cousin Jie’s house, yelling at him to stop crying.

Thus, both men found themselves in this predicament—witnessing the death of their old neighbor and classmate in a foreign land. Cousin Jie recalled the late Mr. Yang receiving many an international long-distance call from his daughter-in-law. At the time, Mr. Yang was already longing to go back home, only to be met by his wife’s wails. How would their son possibly pay his mortgage? In fact, the young man called every month asking for money. What was the straw that broke the proverbial camel’s back for Mr. Yang? Was it the intermediary fee he had to pay in order to leave his native Taiping again to return to Spain? Was it the money he’d had to borrow to pay for it? Nobody would ever find out. Mr. Yang’s older brothers collected tens of thousands of euros for Mr. Yang’s son and younger brother to go to Spain and retrieve Mr. Yang’s remains. Mr. Yang was cremated in a foreign land and his ashes shipped back to China.

Mr. Yang’s final journey home concluded on February 1, 2019, which coincided with Uncle Fu’s tenth day back in Taiping village. At Mr. Yang’s funeral, his son knelt down in the snow piling upon their birthplace, holding the urn with his father’s ashes. During the service, I also saw Mr. Yang's long-lost wife. The middle-aged woman, once plump, was skin and bones. Three days later, the lunar calendar marked the start of the New Year festivities.

***

On March 15, 2019, Uncle Fu's family concluded their two-month holiday in Taiping and journeyed back to Spain. Before he left, Uncle Fu had viewed a few properties in town and instructed his relatives in China to immediately let him know if a good listing came up. He was expecting to return in two years, and wanted to settle in his new residence once that moment came.

By that time, Uncle Fu's daughter and son-in-law were busy working together at a barber shop mostly frequented by Chinese customers; his nephew Xiao Xie and niece Xiao Feng were working at a nail salon where, according to Xiao Feng, Spanish customers were more generous with tips. Uncle Fu’s niece Da Fei was now married and running a small supermarket with her husband. An additional dozen natives of Taiping village, such as Brother and Sister Yong, had also settled in Usera and other areas of Madrid. No doubt they all owed a great deal to Uncle Fu’s continuous support over the years.

In June 2019, Uncle Fu informed me via WeChat that our Taiping neighbors, Brother Hao and his wife, were likely to receive their residence permits soon. I recalled Brother Hao coming with me the day I sent off Uncle Fu’s family at the airport in 2013. On the way back home, Brother Hao had solemnly vowed that one day he would to take his own family to Spain as well.

Written by Mai Cang (麦仓)

Names of people and places have been changed in the piece. The text has been edited to clarify details about Spanish immigration law, with research by Ana Padilla Fornieles.