Is a lack of “aesthetic education” to blame for bizarre architecture and artistic confusion in modern China?

Every year, prizes all over the world are awarded to spectacular architecture. But Archcy.com, a Chinese website on architecture, takes the opposite approach: It has been giving “awards” to the 10 most hideous buildings in China every year since 2010.

The Razzies of the (domestic) architecture world, the “China Ugliest Building Survey” seeks the opinions of a jury of industry experts and invites ordinary people to cast their votes on the website. Notable structures to have received the “accolade” include the Tianzi Hotel in Langfang, Hebei province, an hour’s drive from Beijing, which takes the form of the gods of Fortune, Prosperity, and Longevity in Chinese mythology; the Taiyuan Museum in the capital of Shanxi province, composed of five inverted cones supposedly inspired by red lanterns, but compared by locals to “five extra large ramen cups”; and a wealth of cheap replicas of the Arc de Triomphe, the White House, the Temple of Heaven, and the Tian’anmen Gate.

The aim of the survey, according to the organizers’ website, is to “raise architecture professionals’ sense of social responsibility” and “provoke reflections about what is beautiful and what is ugly among the public.”

While many of the aforementioned buildings have caused no shortage of discussions on Chinese social media, there has been relatively little public conversation around the underlying lack of aesthetic education that may well be partly responsible for such projects.

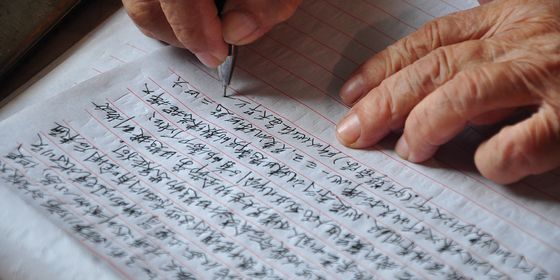

Well-known educator Cai Yuanpei (蔡元培) first introduced “aesthetic education (审美教育)” into China, a concept developed by the German philosopher Friedrich von Schiller. Agreeing with Schiller that aesthetic education served to restore humanity and cultivate morality, Cai imagined that aesthetic education in China would become a substitute for religions and inspire philosophical and spiritual discussions.

After the founding of the PRC, public art in China was dominated by socialist realism, a style developed in the Soviet Union and characterized by its figurative depiction of socialist values, such as brave soldiers fighting for the country and the emancipation of the proletariat. Abstraction, pure formal beauty, or anything devoid of a clear message had little place in revolutionary China. In 1979, in an article entitled “The Formal Beauty of Painting” in Art Magazine, Wu Guanzhong (吴冠中), considered one of the greatest contemporary Chinese painters, advocated for “more independent artworks” that carry formal beauty and no “extra tasks” of conveying certain narratives. The article caused an uproar in the art world at the time.

In the article, Wu shares an anecdote: While painting in the countryside near Shaoxing, he was drawn to the ripples and reflections on a small pond dotted with red and green duckweed; however, he was certain that he would be condemned for capturing such a scene as an “untitled painting,” so he came up with the idea of adding the reflection of red flags and peasants working to make the painting politically fitting.

Since the reform period in the 1980s, a plethora of other art styles started to gradually appear in China, but the preference for utilitarian and literal messaging lingered. In another essay written in 1984, Wu laments that “there are few illiterates today but many who are illiterate in art,” suggesting that the Cultural Revolution has severed the “bloodline of art” and undermined the public’s ability to appreciate beauty.

Today, it can be hard to argue that there’s been a significant change. Of course, examples of excellent contemporary art and architecture abound in China. The Suzhou Museum designed by I. M. Pei, which takes inspiration from the city’s traditional gardens, is one example of a successful marrying of traditional and modern aesthetics; Poetic Dance: The Journey of a Legendary Landscape Painting (《只此青绿》), a Spring Festival Gala dance performance based on the Northern Song (960 – 1127) painting “A Panorama of Rivers and Mountains (《千里江山图》)” is another.

Yet problematic projects continue to emerge. Witness the 10-meter-tall sculpture in front of the Traditional Chinese Medicine Hospital at Qian’an, Hebei province, “Chinese Medicine Goes Out Into the World,” which went viral in 2017: two identical white statues of Li Shizhen (李时珍), a famous pharmacologist from the Ming dynasty (1368 – 1644), standing on a globe bearing the statue’s name in red letters, and a pair of legs protruding from the globe and striding forward. The message has completely overwhelmed the medium.

The appetite for literal expressions has also coupled with a fetishism for projects on a large-scale, aping of foreign styles, and, more recently, elements from traditional Chinese culture. A search in the database of the Jinisi China World Records, a domestic copy of the Guinness World Records, demonstrates an obsession with size when it comes to Chinese architecture and construction. Records include the biggest structure in the shape of an ancient wine jug in Maotai, Guizhou; and the biggest artificial banyan tree in Hangzhou, Zhejiang. The aforementioned Tianzi Hotel also makes an appearance, as holder of the record for the “Biggest Image Hotel.”

While the apparent glory of becoming a record-breaker can’t be discounted as a motive for some of China’s more outlandish structures, there are often other factors at play. “These are not simply a matter of taste,” says Luo Sen, an architect who graduated from the Central Academy of Fine Arts, “but are informed by the value system or even ideology of the decision-makers, and that is difficult for the designers to change.” He explains, “Tianzi Hotel is located in a small city, although it is close to Beijing, so the owner wants to make the building excessively flamboyant to attract visitors.”

Economic interest looms in the background of many government-funded construction projects as well. Regardless of their functional value, such large-scale projects are often major drivers of local GDP growth, or boost the image of a region.

But such desires can prove to be problematic when not moored to a consistent understanding of aesthetics. Some designers on Q&A platform Zhihu have shared instances of requests from clients in that vein: “The boss of a real estate company would travel overseas every month,” one user writes. “During the time we worked on the landscape of one of his properties, he visited the UK, Japan, and Thailand, and after every trip he requested changes to the plan according to the style of the country he visited.”

Problems of this kind are not limited to the architectural sphere. “My biggest headache is that clients and I are not on the same wavelength,” says Du Tingyun, a wedding stage designer. “Often, they don’t even know what they are looking for and just don’t grasp any of the proposals that we have come up with.” A fashion designer working in China, who prefers to remain anonymous, shares with TWOC that her boss “wants to imitate popular products from other brands with no consideration as to whether they can combine to form a cohesive style.”

Both the central government and local administrators have attempted to address problems in public aesthetics. In order to beautify streets, some local governments mandate that shops use standardized signs (which have attracted their own criticism for looking too boring). In a 2016 document, China’s State Council criticized the tendency in urban architecture of “seeking to be excessively big, exotic, and bizarre” and pointed out that buildings should be “suitable, economic, green, and pleasing to the eye.”

In addition to attempting to provide guidance for ongoing projects, there are also efforts to rectify the situation for the future—through the education system. Courses in art have been part of the compulsory education curriculum in China since the 1980s, but the subject is often given insufficient class time compared to those featured in college entrance exams, such as math or Chinese.

In order to boost the importance of art education, a number of provinces, including Jiangsu, Hunan, and Yunnan, have made plans to include art in their high school entrance exams. In addition, with the recent education reforms clamping down on after-school tutoring in academic subjects, extracurricular lessons in the arts have become more popular.

It remains unclear whether standardized testing and formal teaching can help the next generation develop their tastes, however. Educators Li Jian and Xiong Eryong, both from Beijing Normal University, seem to think it’s insufficient. In their 2020 book Shaping Education Reform in China, they point out that “the teaching of art knowledge and skills in aesthetic education should be oriented to help students develop their interest in art, improve their aesthetic ability, and have preliminary artistic creation ability, rather than simply learning knowledge and skills.”

In courses claiming to teach “creativity,” problems exist as well. On social platform Xiaohongshu (RED), a blogger called Liu Chang, who studied architecture at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and now teaches art to children, reveals that extracurricular art classes in China often teach students to replicate identical forms: For example, in a class on creating mushroom-themed art, Liu says, most students will draw a stereotypical button mushroom with a smiley face, while “advanced” students will end up producing a more complex assortment of mushrooms with almost the same composition, only varying in colors. “If [students’] minds have been locked up since an early age,” Liu says, “it’s very painful to try to open them up later.”

As Li and Xiong write in their book, aesthetic ability is “the ability to feel life,” and it seems a consensus among the designers and art teachers that TWOC spoke with that the key to good aesthetic education is the releasing of the mind and soul. “Instead of training students to do certain things,” Luo Sen says, “the most important task should be to help students truly understand themselves in a free and relaxed state, and give them room to be inspired.”

But the anonymous fashion designer feels rather pessimistic: “It will be quite difficult to improve [aesthetic education] because, after all, [at school] students are discouraged from exploring their individuality; if any change is to happen, it might start with breaking the conformity.”

The Ugly Truth: China’s Weird Buildings Have Their Roots in Education is a story from our issue, “Lessons For Life.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.