While English language education was once practically forbidden, decades of reform have turned it into massive business

As the daughter of an English teacher in rural China, I spent my formative years plunked on the floor by the door of her classroom, listening as the room thundered with slogans like, “Long live Chairman Mao!” or “I am a Red Guard!”

When I thought back on this scene years later, I realized that those students probably never had the chance to use any of those sentences. Except for one—a quote from Karl Marx that remains true to this day: “A foreign language is a weapon for the struggle of life!”

In China, this was true as early as the 1940s. When my grandfather was hunting for a job, he learned a popular rhyme to cope with interviewers who asked questions or demanded answers in English: “Diantou yes, yaotou no, lai shi come, qu shi go, yige dayang one dollar, ershier sui, twenty-two” (Nod for yes and shake for no; know the difference between come and go; you want one dollar for salary, and you’re 22 years old). With the help of this formula, he got a job as a Chinese calligraphy teacher and harbored a lifelong respect for English.

That respect did not stay with the rest of the country. By the 50s, Russian was ubiquitous and English was traitorous. Thanks to the Cold War, English had become known as the “imperialist language.” Most people during that time never once saw an English book; they were only sold by a specific department of the Foreign Languages Bookstore, and only to those with certain certifications. The situation changed after China’s relationship with the Soviet Union fell apart in 1956, and Russian gave way to English. Mao Zedong himself was said to be a most avid learner.

My mother was a product of this change. In 1973, after working on farms for five years, she was suddenly summoned for a college entrance exam. At the interview, she was told to read a few English sentences after a tape. Impressed by her articulate pronunciation, the testers promptly put her into the English department.

She started teaching two years later; sometimes, she says, she was the only English teacher in the whole school. “We were teaching Chinglish really,” she says now, laughing at her former self. “In all those years I never once saw a foreigner—we had no idea how they talked!” At the time, there was no up-to-date reading or listening materials, and shortwave radio was forbidden in the 70s.

And so, English was taught from one Chinese to another. They enlarged their vocabulary by memorizing dictionaries, and talked in English with imaginary partners. “Sometimes we had role playing games,” my mother remembers. “Students pretended they were gongnongbing (工农兵, workers, peasants, and soldiers), reciting simple dialogues and shouting slogans.”

Things made a sudden turnaround in 1978, the year Deng Xiaoping introduced his Reform and Opening Up policies. For the first time in decades, Chinese were allowed to apply to study in foreign universities. What was once a tool of “class struggle” turned into a tool for changing individuals’ lives.

Though not everyone was intent on going abroad, learning English was still a window to the outside world. For a decade, a TV program served as that window for millions of Chinese. Starting in 1982, “Follow Me,” the BBC English-learning program, was shown on national broadcaster CCTV three days a week. The BBC didn’t expect China to be a profitable market, and sold the copyright to CCTV for only 3,000 pounds, while in Japan it was several hundred times higher.

As it turned out, it was not a wise bargain for the BBC. After its release, the program immediately garnered an audience of 10 million—which was just about the number of televisions in China at that time. Around 6 every evening, you could begin to hear the intro music wafting out of every household. People were obsessed with this foreign world, which included such wonders as private cars and telephones, along with countless forms of entertainment. My mother still remembers the handsome main character Francis Matthews, as well as another show called “London Quiz.” “That was real English!” she exclaims.

The British hostess of the program, Katherine Flower, was impressed by Chinese people’s enthusiasm. “One young man wrote out the scripts of some of the programs in a notebook, and drew pictures and illustrations,” she recalled.

In the 1990s, English learning continued to gain popularity, and new, bestselling textbooks began to spring up like mushrooms, names that are still famous today, like New Concept English, Victor English, and Family Album USA. Soon, the dreamy Francis Mathews made way for fresh characters. Han Meimei and Li Lei were two of the most prominent of these, appearing in the new version of the official English textbooks introduced nationwide in 1990. This series dominated middle schools for a decade, and Han and Li became pop icons for the entire post-80s generation.

By the 2000s, English proficiency had begun to play a role in every stage of academic and professional development. In 1983, a passing grade on English exams became a prerequisite for high school; in 1984, it was entered as a requirement for university admittance; and in 1999, it was established as another high bar for a professional title.

As English has taken on not only a prominent but an unavoidable role in achievement, people are beginning to question whether its importance is exaggerated. The controversy was brought to a climax in 2000, when Chen Danqing, a professor at Tsinghua University as well as a dedicated artist, quit his job over the question—or rather, the answer.

Chen was already a legend in the field. When he took his English exam in 1978, the only thing he wrote on the paper—in Chinese, no less—was, “I was been a ‘sent-down youth’ [dispatched to the countryside] during the Cultural Revolution. I’ve never gone to school.” Though he got a zero on his English test, Chen nevertheless was admitted into China’s Central Academy of Fine Arts.

But that was more than 30 years ago. By 2000, the professor had failed to recruit a single student for four years in a row, because the top art students could never pass the English exams. “In addition to these, there are thousands of kids each year who love painting but can’t get into art schools, just because their English is not good enough,” he protested on a talk show. “And there is nothing I can do.” Eventually, Chen quit his job in protest of the educational system.

Chen was heralded as a hero for speaking out. However, the artist’s wish—to abolish the English proficiency requirement in universities—was hardly realistic. These days, people are busier coping with this reality than protesting it. Parents pinch and save to send their children to expensive bilingual kindergartens, while adults swarm to English training centers.

English abilities have become vital even in environments where they’re not necessary. One of my friends quit her job at IBM because she was the only one of her colleagues who couldn’t write emails in English, a fact that was wearing down her self-esteem. This was in spite of the fact that all of her colleagues were Chinese, and there were no foreigners involved in their correspondence.

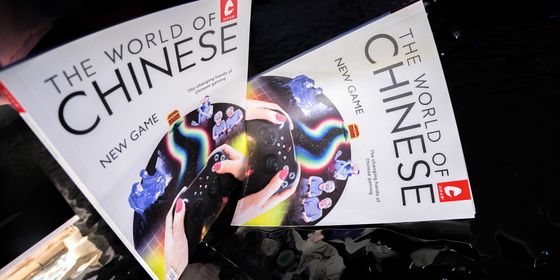

My mother, on the other hand, thinks the English craze is a sign of much needed internationalization. Though she retired three years ago, she remains the English teacher in the family. Under her tutelage, Dingding, my 2-year-old son, can already count to 20 in English. “What else can we do?” she asked me. “This is a world where you need English for everything. Even Dingding needs to learn English in order to play video games.”

Additional research by Ginger Huang

This is a story from our archives: It was originally published in September 2011 in our issue “You Don't Understand Me!” and has been lightly edited and updated.