From controversial kiss scenes in movies to stolen trysts by the riverbank, here’s how China rediscovered kissing after the Cultural Revolution

In 1979, a national controversy broke out across China—about kissing.

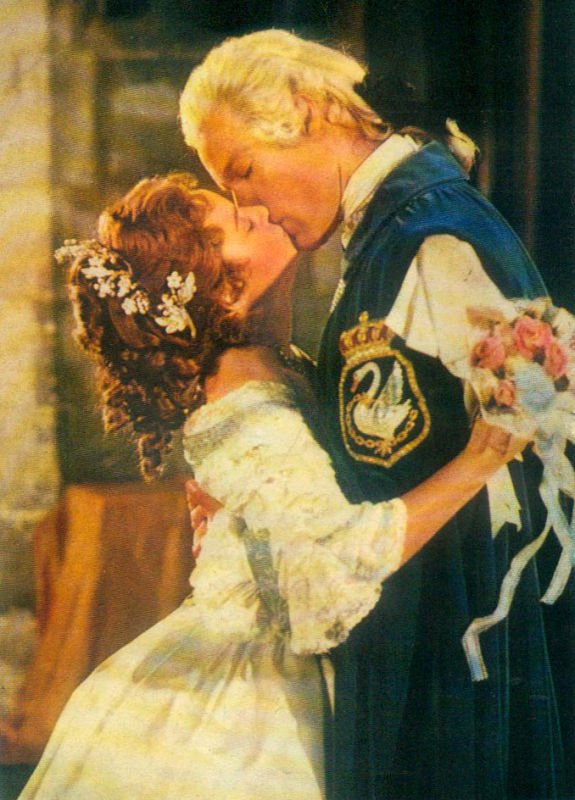

It started with a photo on the back cover of Popular Cinema, the only color magazine in China back then. It was a stylized photo of a kissing scene from The Slipper and the Rose, an English film based on the story of Cinderella.

Soon an angry letter landed on the editor’s desk. It was from Wen Yingjie, a clerk from a propaganda office in Xinjiang. Wen called the publication of the photo “decadent, capitalist, an act meant to poison our youths,” and asked, “Are kissing and hugging the things most needed by our socialist China?” Further, he demanded, “It’s not that we don’t want love; the point is what kind of love we want—pure, proletariat love, or corrupted, capitalist love?”

Wen further challenged the editors to face their crime and publish his letter. The editors complied, and invited other readers to voice their opinions. In an age before internet, people wrote. In two months, over 11,000 letters flooded into the office. “The postman was exhausted. Every day he had to carry in two sacks of letters,” one of the editors recalled. Neither Wen nor the editors expected such a massive public debate.

After two months, the magazine announced the outcome of the debate. In an article titled “Spring is not to be stopped by the cold,” they revealed that less than one-third of the incoming letters supported Wen, the righteous propaganda worker. People wanted to see a handsome man and a beautiful woman kiss. “We published it because it was a good-looking photo,” the editor-in-chief said.

1979: Kisses Seen ’Round the World

Considering the culture climate of his time, Wen wasn’t exactly being a prude about the photo. Long Feng, a man born in the 1960s, only saw kiss scenes in Eastern European films as a child. He asked his father “Why do foreigners kiss a lot?” His father replied impatiently, “Because they’re foreigners. Only foreigners do that.”

Of course, this wasn’t true. People kissed in Chinese films as early as the 1930s; people also kissed in classical literature. But times were special when Long asked his question.

In the 1960s, the notion of “class struggle” was paramount. Kissing and hugging were considered capitalist and degenerate. People lived in fear of being accused of zuofeng wenti (作风问题). This literally meant “problems of lifestyle,” but really it referred to illicit affairs. If someone was found to have a problem with his or her “lifestyle,” that person would be humiliated, alienated by friends and punished criticized by their danwei (working unit). In a country with little social mobility, a problematic lifestyle could completely ruin one’s life.

It was very easy to be charged with with the fatal zuofeng wenti. Being seen holding hands in public being was just one way of eliciting the accusation. Any kind of closeness with the opposite sex could give rise to rumors. In films, healthy, proletarian ways of expressing love included lending books to each other; giving fountain pens and notebooks as gifts; and talking about revolutionary ideals instead of personal things when alone together. When critical moments came, when the characters needed to declare their love, it was customary for women to bury their faces in their hands and for men to scratch their heads with dumbfounded modesty. During the Cultural Revolution, even these scenes were banned. “It was a sexless society,” Pan Suiming, a sociologist, once said of Chinese society then.

After steering clear of “unhealthy, capitalist” ways for 30 years, the public became obsessively drawn to anything amorous. The Tremor of Life was a musical film shown in 1979. It was an honest representation of the political purges that took place during the Cultural Revolution. It had two beautiful, melancholic leads and good music. It was meant to help people cope with trauma. But, the biggest drive for its audience wasn’t healing, but a kiss. The Tremor of Life was the first film to try to show a kissing scene after 1949. Before the film was released, rumors circulated that the actors had put plastic wrapping on their lips before filming the kiss.

In a full house, when the moment of kissing came, the audience was so quiet that they could hear water running through the theater’s heating pipes. All eyes were trained on the screen trying to identify the plastic wrapping. Just as people held their breath at the critical moment, the mother-in-law broke into the room on-screen, and the lovers parted. The whole theater sighed in disappointment. It seemed that kissing was even more of a taboo than examining brutalities of recent history.

1980s: Stolen Kisses at the Forbidden City

Young people remained discreet in the early 1980s. Although being seen together was no longer considered “hooliganism”(耍流氓),” a criminal offense sometimes punishable by death from 1979 and 1997 in China, couples rarely held hands in public and could only kiss in certain locations—secluded bushes where no one else could see them, or in areas considered to be common “kissing spots,” like on park benches or along riverside lane, where one could count on passersby to look the other way.

“We were like underground agents,” Xiao Yu, a middle-aged man recalled his dating experience to TWOC. “When we went to the movies, we walked apart as if we didn’t know each other. Only the bold couples dared to go into the woods and kiss, like characters in films did.”

The first film that taught young people about kissing was 1981’s Romance on Lushan Mountain. By today’s standards, Romance on Lushan Mountain is a weird film. It is a boring love story with little drama and bland conversation. When it’s time for the characters to say, “I love you,” they say, in English, “I love my motherland. I love the morning of my motherland.” There is a kiss, but it is just a quick, light peck on the cheek. Young people nowadays laugh out aloud when they watch it.

In 1980, however, the audience was different. They were intrigued. The lead actors had never tanlianai (谈恋爱, been in a romantic relationship) themselves; neither had the majority of the audience. Because few people said “I love you” to each other in real life, few found it odd that the lovers shouted “I love my motherland” instead. They were just excited to finally see a film that was not about revolution or class struggle, but simply a relationship. It was the most watched film for several years in a row.

The Lushan kiss scene was shot on the top of a lonely hill. Yellow lines demarcated the set two miles away from the action. No one was allowed to stand by to watch except the director and the cinematographers. Still, these precautions didn’t help the actors’ nerves. “I was so nervous I couldn’t find his lips,” Zhang Yu, the female lead, confessed 30 years later. “I meant to kiss him on the lips.”

Although she missed, the kiss was legendary. The flirtation in the film, like the kiss, was simple and innocent. The lovers chased each other in the woods and talked on a lawn. Young people left the cinema and imitated the characters. After all, after decades of repression, tanlianai was something new. No one knew how to do it. Films were a major source for educating people on how to act like a couple.

The 1990s: Kissing, Sex, and Rock ’n’ Roll

As materialism sped up under the reform policy in the 1990s, people’s lifestyles rapidly Westernized. They embraced rock ’n’ roll, supermarkets, fast food, Hollywood films, and a more open attitude toward sex. China’s first sex shop opened in 1993. A group of young women writers started to write openly about their intimate physical experiences. Fashion magazines introduced sex columns. Kissing was no longer an issue—it hardly drew attention, in films or in reality.

That is, unless it is forbidden: In 2003, Shenzhen University laid down a new rule that students were not allowed to “hold hands, hug, or kiss” on campus, and quickly became the target of satire. Xinhuanet published opinion pieces crying for “the right of kissing on campus” and questioning the legality of such rules. Sina.com commented in its social column, “If you feel uncomfortable seeing people kissing or hugging, that is your problem.”

Clearly, attitudes on kissing have changed over the last 30 years. What would Wen Yingjie say if he saw the state of capitalist decadence today?

This is a story from our archives: It was originally published in March 2011 in our issue “Lights, Camera, Action,” and has been lightly edited and updated. Check out our online store!