Brutal assault in Tangshan renews calls for better education on sexual consent in China

The most shocking story on Chinese social media last week started with a rejection. As shown by surveillance footage from a barbecue restaurant in Tangshan, Hebei province, at around 2:40 a.m. on June 10, a seemingly inebriated man wobbled over to a woman dining with friends, rubbed his hand on her back, and muttered what sounded like obscenities, to which the woman responded by pushing him away and yelling, “What’s wrong with you?”

This “no” was not taken well. The man slapped the woman in response, and when one of her female companions retaliated, he and his male companions launched into an all-out assault on them—with bottles smashed, chairs thrown across the room, one woman dragged outside by her hair to continue the beating, and other women battered when they tried to intervene.

As the internet boiled over with outrage about the brutality and the local police’s seemingly slow reaction, Qianqian Law Firm, a Beijing-based firm which specializes in legal aid and women’s rights advocacy, reminded the public that this is not an isolated event. In an article posted on its WeChat account, the firm lists six vicious events since 2020 from Shanxi, Zhejiang, Anhui, Sichuan, Shandong, and Yunnan provinces, all of which feature women who experienced violent retaliation after turning down sexual harassment, with two cases leading to the death of the victims.

In July of last year, following the notorious sexual assault exposé involving actor and singer Kris Wu—whose case coincidentally had its first hearing on June 10, the day of the Tangshan incident—the hashtag “What exactly is sexual consent” reached more than 380 million views on Weibo. Despite this, and increased efforts by grassroots organizations to raise awareness, patchy education, legislation, and law enforcement still seemingly leave many confused on the definition of sexual consent, victims of sexual assault still lacking places to turn for help.

Katharine Zhang, a woman in her mid-20s living in Beijing, tells TWOC that she feels “very helpless” in the wake of the Tangshan event. She is reminded of an experience she had last year, when an anonymous user on messaging app QQ started adding her acquaintances and friends to spread rumors about her personal life. Zhang has reason to believe the perpetrator is a man whose request for a casual relationship she rejected a few years ago.

In August 2019, Alex Chang, a feminist blogger on Weibo with over 1 million followers, hosted a pop-up exhibition about sexual consent in a bar in Beijing. Chang decorated the walls and ceilings with print-outs or projected quotes showing all kinds of excuses or strategies women use to turn down a request for sex or intimacy, which Chang had collected from her followers. Some of the quotes read, “I suddenly got my period” and “My room is messy,” while others described efforts to change the topic.

In a video Chang later shared on Weibo, several female participants in the event explained that in situations of unwanted attention, they do not directly voice their lack of consent, wanting to “save face” for the men in question. This echoes some commenters after the Tangshan incident who, well-intentioned or not, suggested the victim had made her first assailant “lose face” by giving him a direct, public rejection. However, another participant in the project shared that she was forcibly kissed by a man even after she protested, and then told that she was reciprocating because she did not dodge his advances. “But in reality I was unable to dodge. He was strong,” she tells the camera.

But while some are struggling to build a culture of consent, others contribute to blurring the boundaries. In a video that courted widespread criticism last year, Dalieba, a user on video-sharing platform Douyin who has attracted 1.6 million followers with her male-oriented relationship advice videos, told her followers that it’s sexually suggestive if a woman brings a hair elastic to dinner with a man. “She’s afraid you might lie down on her hair later,” she says with a knowing laugh, and then encourages viewers to try suggestive jokes with such women.

Though the video can no longer be found on Dalieba’s Douyin page, according to a December article by Girls Don’t Be Afraid, a feminist WeChat account, some male viewers commented they were eager to try out the trick. “What if there are boys who really took the message, and start reading too much into a normal hair elastic and getting handsy?” Girls Don’t Be Afraid voiced concern of how this could blur the line of consent.

In a 2021 episode of pop culture podcast The Weirdo, guest Alexwood, who runs a media platform focused on gender-related issues called Biede Girls, points out that, “In [Chinese] culture, ‘no’ might be understood as flirting, as agreeing without agreeing.”

Referring to traditionally conservative attitudes toward sex, she theorizes that some men might think “all women say no; what kind of woman would say yes?” Chinese movies and TV shows that romanticize the domineering men forcing a kiss on their love interests might have contributed to confusion about consent, observes Alexwood and the podcast host Ruohan. The same could be said of the Japanese anime many Chinese have grown up watching, in which yamete, the Japanese word for “stop it,” is often used flirtatiously.

The PRC’s Criminal Law dictates that “whoever, by violence, coercion or other means, rapes a woman” can be sentenced to prison terms between three to ten years, and sets similar punishments for anyone who “forces, molests, or humiliates a woman.” “Legal writing is highly rigorous, logical, and concise, so it’s impossible to spend too much space describing so-called consent,” Lü Xiaoquan, the executive manager at Qianqian Law Firm explains to TWOC over WeChat. But he lists a broad number of examples that can be covered within the Criminal Law’s parameters of ”violence,” ”coercion” and ”other means.”

Jin Lin, a lawyer at Beijing’s Jingshi Law Firm, offered context to China News Weekly in August 2021: “‘Violence’ means the victim cannot resist, ‘coerce’ means she dares not to resist, and ‘other means’ means she is not aware she can resist or lack awareness she is being taken advantage of.”

Jin points out that whether the victim has given consent is the key defining factor in rape cases, though court practices in China tend to abide by the “no means no” standard of consent, seeking evidence that the victim resisted the aggressor. By comparison, affirmative consent, commonly known as the “[only] yes means yes” standard, is catching popularity in countries including US, UK, and Australia, and places less burden of proof on the victim.

Many US universities wrote affirmative consent into their campus policies in the early- to mid-2010s, following many high profile cases of campus sexual assault that shed light on how the “no” standard places a heavy burden of proof on victims and can discourage them from reporting sexual assault. Just this past month, the Australian state of New South Wales reformed its sexual consent laws to set clear boundaries for consensual sex, using affirmative consent as framework.

“Sometimes it’s not even about whether you give consent. You don’t even have a chance to consent,” Zhang sighs. She shares that an acquaintance from the gym whom she had not talked to for a year suddenly called her up at 2 a.m. one night, confessing his feelings for her. “Then he said, ‘I’m outside your building. Open the door,’” recalls Zhang in horror. “I don’t even know how he found out where I lived.”

Formal education is also lagging behind. In China, “[the education on sexual consent] is mostly through teaching kids about their private parts,” Chen Jing, a sex educator based in Shanghai, tells TWOC over WeChat. Attempts to deviate from this curriculum or offer more comprehensive education about coercion, gender stereotypes, and power imbalances can attract pushback from parents and other conservative voices, as TWOC found out in an earlier investigation about sex education in China.

Famously, Cherish Life, a series of comprehensive sexuality education textbooks created by a team led by China’s leading sex educator Liu Wenli, was pulled off all sales channels in 2019 and has not yet been reinstated at the time of writing, due to parents and bloggers complaining it promoted homosexuality and “spoiled” their children. The books had featured chapters that teach children to recognize when an adult violates their boundaries, to say no to situations they do not want, and inform trusted adults of experiences that made them feel uncomfortable or afraid.

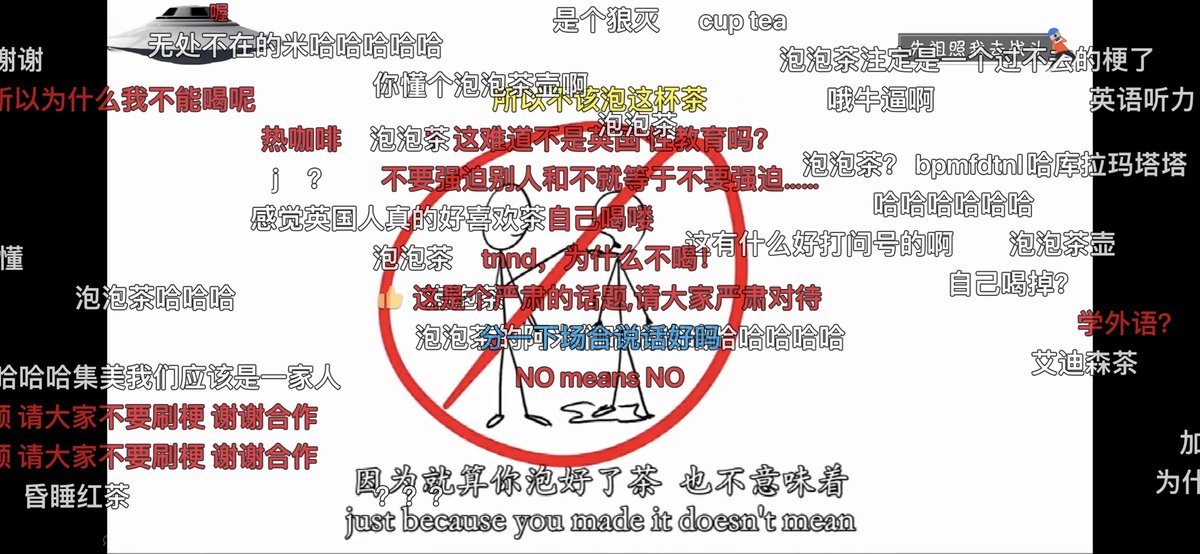

But sex educators and growing numbers of voices in Chinese society feel sex and gender education should be about more than just protection. A search for “sexual consent (性同意 or 性许可)” on Bilibili, a Gen Z-targeted video-sharing platform, gives results from vloggers across genders, many of them trying to raise awareness and using personal experiences to debunk the mindset that a lack of resistance can be seen as consent. A Chinese-subtitled version of “Consent is Simple Like Tea,” a famous cartoon made by the UK’s Thames Valley Police that humorously likens sexual consent to agreeing to drinking tea, has drawn more than 2 million views on Bilibili. Many users expanded on the video’s analogies with comments like, “If I took a sip but realized the tea is not tasty, then no one should force me to keep drinking.”

“We need to teach kids about gender equality from a very young age, and teach boys to respect women and not to harm women,” says Zhang. Despite unpleasant scenes she had witnessed or heard from friends, and horror stories in the news, she says most men she has met are “well-mannered,” so she remains hopeful. “Nowadays, more and more women have awakened, and more and more men are learning to respect women. I’m sure [they] will teach their children well.”

At the same time, she thinks, “Women should stand up, to compete for the same resources as men and the same rights to speak. Only when there are more women in the political and legal spheres can we fundamentally change this situation.”

Additional reporting by Hatty Liu and Alex Colville