Grassroots organizations and social media are filling a wide gap in China’s formal sex education

Sex education can provoke awkward giggles at the best of times, but a viral new video on Bilibili, a Chinese platform popular with Gen Z users, takes things up a few uncanny notches: featuring a still photo of a lemon with a human mouth and eyes, rapping about sexual confusion and confessions in the (auto-tuned) voice of a young Chinese person growing up.

Created in February 2022 by Meng Cong, a 33-year-old freelance psychotherapist (whose own eyes and mouth are layered over the lemon), the bizarre yet candid video reflects Meng’s earliest sex education, or lack thereof: being told that people automatically become pregnant upon marriage; discovering pornographic videos in the sixth grade; peeping on their older sisters in the shower out of curiosity about girls’ physical development. The video has attracted more than 2 million views and 8,683 comments at the time of writing, many of them poignant personal experiences from viewers.

“I cried so many times reading the comments and felt heavy for a long time,” Meng tells TWOC, referring to the public comments as well as private messages from users who shared memories of being shamed by teachers for talking about menstruation, or how the lack of knowledge exposed them to childhood sexual assaults from strangers, neighbors, cousins, or even fathers. As one comment summed up, “In China, students rely on themselves for sex education”—while the formal education system has been slow to catch up with young people’s increasingly urgent and emotional demand to learn about sex.

In a 2020 evaluation on young people’s sexual and reproductive health, the China Family Planning Association, China Youth Network, and Tsinghua University surveyed 54,580 students from 1,764 universities around China. While 68 percent admitted to seeking sexual knowledge online, only 52 percent had received some form of sex education in school. Out of the nine basic questions about birth control and sexually transmitted diseases included in the survey, students achieved an average score of 4.16 out of 9.

For Meng, the only formal sex education he recalls was “two pages of a biology textbook, maybe in seventh grade.” He is unsure if the teacher spent even half a class to go over the content, but clearly remembers how his cheeks burned with shame.

Meanwhile, sexual assault cases of minors are rising to public attention in recent years. Waves of breaking news have made parents anxious to protect their children from such tragedies: from allegations of child molestation in a Beijing kindergarten called RYB Education in 2017, to discussions on trafficking of young women sparked by the woman found chained to a shed in Xuzhou, Jiangsu province, in early 2022. The sexualized internet environment (despite China’s reputation for strict censorship) also leaves those seeking proper sexual knowledge one click away from misleading content.

On October 17, 2020, the term “sex education,” or 性教育, was finally written into Chinese legislation for the first time, as a new revision to China’s Law on the Protection of Minors that stipulates that schools and kindergartens carry out age-appropriate sex education. The law, though, puts sex education only in the context of “awareness and ability of self-protection against sexual assault or harassment,” without specifying on how this education could be carried out.

Before this change, documents from the Ministry of Education, which has tackled sex education since 1988, used euphemisms such as “adolescence education,” or broke the curriculum down into separate topics such as health, ethics, anti-bullying, and sexual assault prevention.

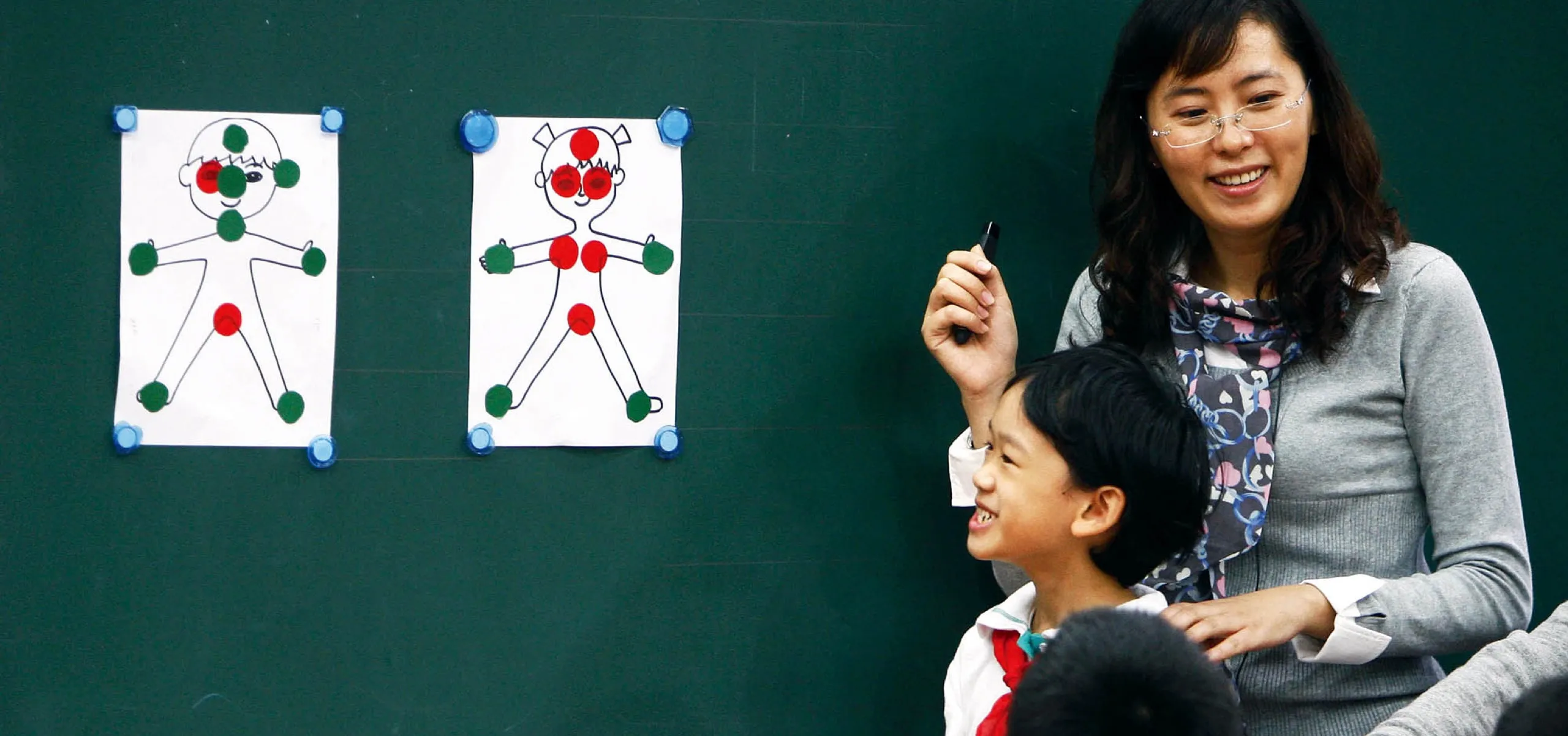

“Traditionally, Chinese people view [sexuality] as a sensitive topic,” says Luo Wei, a math teacher at a public school in Jiaxing in east-central China’s Zhejiang province, who also doubles as a school psychological counselor. She tells TWOC that the only consistent, school-wide “adolescence education” offered to her students involves two lectures by experts from local hospitals to (usually embarrassed) fifth graders, separated by gender, about the changes their bodies go through in puberty and ways to protect themselves from harassment or abuse. “Jiaxing is a small place, so we are not as open-minded as the big cities.”

Teachers also find themselves lacking in relevant knowledge. Luo wants more training in sex education for herself and colleagues, “Or else, like now, we wouldn’t know how to answer if students have questions…except from our own personal experiences.”

While legislation and traditional schools are trying to catch up, grassroot efforts are rising up to meet demand for sex education, especially in major cities. Wang Wei, the 24-year-old founder of youth sex education organization Maylove, says that a conversation in high school with her roommates about an unpleasant encounter with an exhibitionist at a bus stop led her to discover that about a quarter of girls around her were struggling with boxed up memories of sexual harassment and assaults.

Today, the young team at Maylove—with an average age of 22—runs a WeChat account with around 400,000 followers, which is updated daily with humorous but research-based articles meant to directly address concerns that people their own age have shared about sexuality, from sex toys to post-coital dysphoria to gender-based power dynamics. In addition, the organization has given lectures in secondary schools and universities, and recently released an online course for teenagers.

In fact, social media in China is teeming with resources for young people hungry for sex education. A search of the term on Bilibili returns about 1,000 results. Besides Meng’s lemon avatar, there is “Self-Reliance,” a live-action interactive video game created (with low production value) by Shanghai high school students with scenarios such as unplanned pregnancy or giving sexual consent. Another highlight is Dr. Liu Wenli of Beijing Normal University, one of China’s most famous sex educators, whose videos show her clad in a formal-looking blazer and answering questions like “Can you mention words like ‘penis’ and ‘vagina’ to children?” and “What to do if your child accidentally sees you having sex?”

Since 2018, Wang has found new ways to make conservative school administrators more open to Maylove’s services. For example, by collaborating with a reputable official institution, the Shenzhen Disease Prevention and Control Center, Maylove is able to go into schools to give lectures on HIV prevention, and tack on content such as adolescent development and pregnancy prevention.

When visiting middle and high schools, Maylove speakers are usually allocated one or two classes. “It’s hardly enough time to finish what we want to talk about,” Wang tells TWOC, over the phone from Shenzhen. “Secondary schools have tight schedules. They want students to spend every minute studying.” To avoid competing for class time, Wang is now thinking about creating more immersive sex education through installing exhibitions on campus.

Chen Jing, founder of Evolving-I, an organization in Shanghai providing support in sex education to parents and schools, tells TWOC that eight years since their founding, Evolving-I still has to deal with school administrators’ misconception of what sex education entails.

“I would tell the principals: We don’t call it ‘health and hygiene’ anymore. We call it ‘comprehensive sexuality education’ now,” says Chen, referring to a curriculum-based method recognized by the United Nations that addresses sexuality through its cognitive, emotional, physical, and social aspects. Evolving-I’s CSE syllabus includes gender roles, gender diversity, relationships, sense of responsibility, information literacy, and rational decision making. “They are usually shocked by this point.”

Even when some schools step forward to seriously incorporate CSE, they encounter pushback from the rest of society. In 2017, a parent in Hangzhou complained on Weibo about Cherish Life, a series of CSE textbooks adopted at her child’s school, created by a team led by Dr. Liu. The parent objected to illustrations of sexual harassment and intercourse, which many parents on social media felt would encourage imitation. “Parents might think that [by offering sex education], the school has spoiled their children, making them less innocent,” Chen says from her experience teaching in public, private, and international schools across China.

Public opinions also diverge, which forces educators to walk a fine line. In 2019, several bloggers and vloggers condemned Cherish Life for promoting homosexuality, and the books were taken off all sales channels. As of 2021, the textbooks were still “undergoing revisions,” according to Liu’s Bilibili channel, and not yet reinstated.

An interactive exhibition Maylove put on in Shenzhen in the summer of 2021 was seemingly reported to local authorities. Before it opened, the organizers faced with rejections from event spaces and funders, many citing sensitivity of sexual topics in the public discourse. Many sex education content providers online, such as “Sex Filled Cheese,” a Bilibili account with 2.3 million followers, self-censor as a precaution, replacing keywords like “intercourse” with a “beep” sound or euphemisms like “clapping for love,” so as not to trigger the platform’s censors.

“We are so careful about how far we go,” Chen shares, “just so we can protect our mission, making it more sustainable.”

Educators are also divided on how far they should go to protect children. While Liu’s videos stress the importance of using scientific terminologies before children to build body awareness and demystify sex, Chen recommends using the term “birth canal” for vagina among young children so they will not be judged, in China’s conservative social environment. Liu worries that using euphemisms would add to children’s aversion to talking about sex, but Chen believes localization is needed to make sex education acceptable in China’s cultural environment.

Sex education shouldn’t just be about danger and protection, but should also be about love, Liu suggests. In a video addressing the scenario of a child accidentally walking in on parents having sex, she recommends that, in addition to establishing better boundaries and privacy, parents can explain to children it is a way they express love to each other.

“[Sex education] affects how we view things, our values, how we interact with people, and how we see the world,” Wang echoes. “It’s an education of life, and of personhood.”

Let’s Talk About Sex (Education in China) is a story from our issue, “Lessons For Life.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.