Hair was almost sacred to some ancient Chinese, and hairdressers eventually cashed in

On June 1, when Shanghai finally began to exit a grueling two-month lockdown, many people’s first port of call was the hair salon. People queued for hours to see their favorite stylist, while others gave up on a salon cut and got their trim on the street from enterprising barbers who brought their equipment outside.

Some had gone three months without a trim, and begun to grow new lengthy styles—something Confucius surely would have approved of, as in ancient times, Chinese wouldn’t cut their hair for just any reason. Indeed, the sage once said: “Our body, hair, and skin are given by our parents and we shouldn’t damage them lightly. That is the first step of filial piety.”

From the Xia dynasty (2070 – 1600 BCE) to the Eastern Han dynasty (25 – 220), cutting off all or parts of one’s hair was a harsh penalty dished out to criminals, known as “髡刑 (kūnxíng).” Though hair-cutting wouldn’t cause physical harm, it would ruin one’s social standing and immediately mark out the shorn individual as a criminal in public. According to the Book of Jin (《晋书》), in the Three Kingdoms era (220 – 280), historian Chen Shou (陈寿) witnessed his father suffer a haircut for poor leadership on the battlefield when assisting general Ma Su (马谡) of the state of Shu in battle against the state of Wei.

But keeping long hair didn’t mean letting it grow unrestrained. Ancient Chinese cared deeply about their hairstyle, and had their own sophisticated hairdressing methods.

According to the Records of the Origins of Affairs and Things (《事物纪原》), a reference book compiled in the Song dynasty (960 – 1279) tracing the origins of creatures and traditions in the reign of mythological ruler Suiren Shi (燧人氏), people began to wear their hair in a bun during Suiren’s reign over 4,000 years ago. At that time, though, they simply tied their hair in knots, without assistance from any hairpins or accessories. Later, after the daughter of Nüwa (女娲), a legendary goddess believed to have existed in a similar period with Suiren Shi, created rope with wool, people began to tie their hair up with rope. Later, people began using silk and cloth, and made the earliest kinds of hairpins, known as “笄 (jī),” from tree branches and bamboo.

In the Zhou dynasty (1046 – 256 BCE), tying up one’s hair became part of the coming-of-age ceremony for people of the Central Plains. The ceremony for boys was called the “capping ceremony (冠礼),” which was held when a man turned 20. During the ceremony, the man’s hair would be tied up in a bun, and a senior relative would fix his hair with a cap or crown. According to the Book of Rites (《礼记》), a collection of texts mainly published in the Han dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE) on society and politics of the Zhou era, “the capping ceremony was the basis of all rites.” A person could be identified as an adult by their hair arrangement.

Women also took part in a “hair-pinning ceremony (笄礼).” According to records in the Book of Rites and the Book of Etiquette and Ceremonies (《仪礼》), a text completed in the Spring and Autumn period (770 – 476 BCE) also on customs of the Zhou dynasty, the hair-pinning ceremony would be held when a girl got engaged or turned 15. At the ceremony, a married senior relative would comb the girl’s hair, put it into a bun, and fasten with a hairpin.

Hairdressing would also include washing one’s hair (沐) and combing hair (梳 or 栉). The earliest record of hair-washing in China is from the Classic of Poetry (《诗经》), the oldest existing collection of Chinese poetry, comprising 305 works dating from the 11th to 7th centuries BCE. A poem titled “Collecting Herbs (《采绿》)” describes a woman who, so distracted by her longing for her husband, cannot concentrate on her work of collecting herbs and instead begins to think about her hair: “I spent the whole morning collecting herbs, but just a handful. My hair has become curled and tangled. Why not go back to wash it?”

By the Warring States period (475 – 221 BCE), combing and trimming one’s hair had already become a daily routine. In 2002, archaeologists found a dressing case from an ancient tomb in Zaoyang, Hubei province, which contained a mirror, a comb, a powder box, and a razor.

In the Song dynasty commercial hairdressers began to appear in significant numbers. Known as “tweezers workers (镊工)” or “comb workers (栉工),” these craftsmen could earn a decent living. Writer Zhang Duanyi (张端义) recorded in his Gui’er Ji (《贵耳集》), a book collecting anecdotes of the Song dynasty, that the infamously corrupt chancellor Qin Hui (秦桧) once paid 5,000 wen for a haircut, enough to buy about 120 kilograms of rice at that time.

In Lin’an, the capital of the Southern Song dynasty (1127 – 1279), the hairdressers even formed an industrial association, called the “hair-dressing community (净发社).” The members of the association, known as “hairdressing artists (净发艺人),” established an industry guidebook, which was titled “Instructions on Hairdressing (《净发须知》).” The guidebook listed 10 requirements for hairdressers, not only calling for them to have excellent professional skills, but also to be good-looking, intelligent, eloquent, and easygoing, so that they could provide good service.

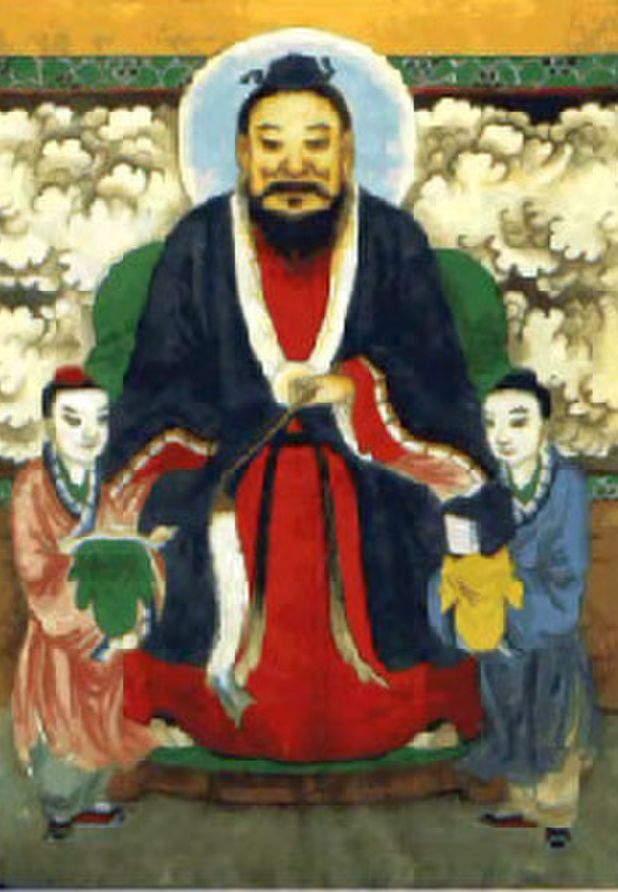

The book even identified the supposed founder of the hairdressing industry: a Daoist priest surnamed Luo who lived during the Tang dynasty (618 – 907). Priest Luo learned hairdressing skills at the age of 7, and had even dressed the hair of Emperor Xuanzong.

A folktale describes Luo’s expertise. During the reign of Empress Wu Zetian, Luo volunteered to dress the hair of a cruel and tyrannical prince who had killed numerous hairdressers in the past for their poor handiwork. Despite the prince’s notoriously odd-shaped head, Luo worked his magic, the prince was extremely satisfied, and never killed another hairdresser again. To thank Luo for saving their lives, hairdressers began to worship him as the ancestor of the industry. Luo is still widely worshiped today, and old-fashioned salons may even display his statue.

In the Qing dynasty (1616 – 1911), hairdressing, or rather hair-shaving, became essentially mandatory since the Manchu rulers forced non-Manchu men to adopt the pig-tail “queue” hairstyle. Among their own people, Manchu culture also placed importance on maintaining one’s locks, with imperial consorts forbidden to cut theirs except at the death of the emperor or his mother. With non-Manchu subjects forced to get their head shaved or be put to death, many hairdressers carried their trimming tools and a small stool from street to street to attract business—not much different from those entrepreneurial stylists setting up shop on the roads of reopened Shanghai today.