Excess packaging creates millions of tons of waste each year. What can China do about this problem?

The cardboard box sits half-empty, filled with eight 125-gram cups of yogurt on foam trays spaced two finger-widths apart. Each is crowned with a thick plastic blue dome—supposedly a tribute to the seaside architecture of Santorini, Greece—that can be fixed to the bottom of the cup as a base, turning it into a “goblet” that “instantly unlocks a sense of ceremony” for the yogurt-eater, according to the description on the label.

A winner of the prestigious iF Design Award in Germany in 2021, this new product packaging unveiled by Ambrosial, a popular Chinese Greek yogurt brand, has elicited a mix of unintended emotions among ordinary consumers—speechlessness, confusion, and anger. A forum on social media platform Douban called “Pissed Off by Overpackaging” dedicated two posts to it. One of the 23 comments reads, “Other examples of excessive packaging either look pretty or protect the product. This does neither. It’s nuts.” Another states, “It looks like a fucking toilet plunger.”

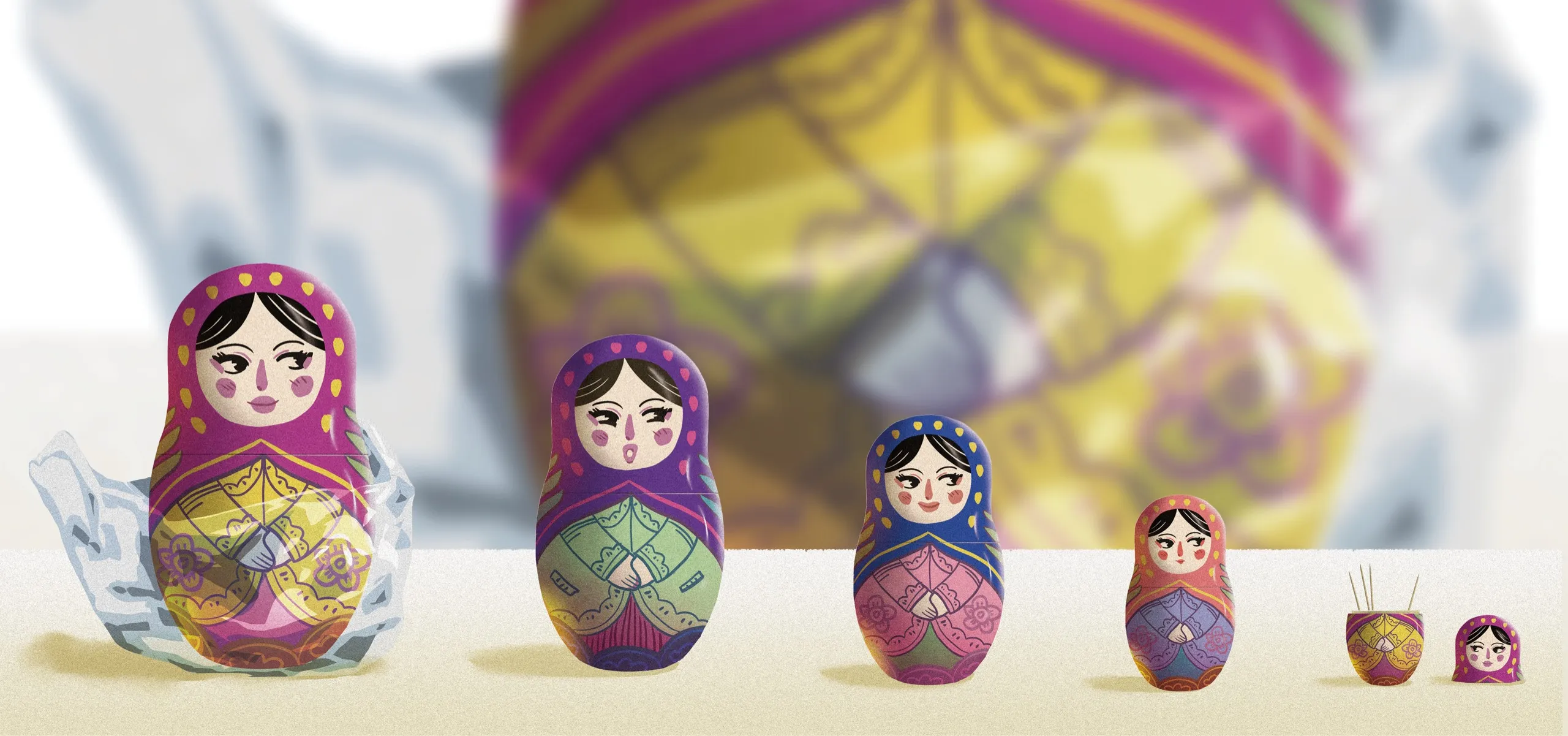

The 12,126 members of the Douban forum have compiled an excess packaging hall of shame: kumquats in individual plastic wrappers, nuts swaddled in two redundant layers of paper bags, three meters of bubble wrap protecting a roll of correction tape, and mooncakes from China’s Mid-Autumn Festival—a product notorious for overpackaging—that are each placed in a plastic tray, encased in a clear plastic shell, put in individual paper boxes, and sold in batches of four in a flamboyant red-and-gold hard case lined with foam.

In 2020, annual household waste in China’s cities soared to 235 million metric tons, among which “packaging waste makes up 30 to 40 percent,” noted Chen Hongjun, deputy director of China’s State Administration for Market Regulation (SAMR), during a press conference in September 2021, announcing new updates to national standards introduced in 2009 to curb excessive packaging in foods and cosmetics.

There are more serious consequences of overpackaging than exasperated consumers. “When we throw out the packaging, it’s not like it gets taken away by a little fairy and disappears,” Alice Chen, a 22-year-old researcher at a think tank focused on green finance, tells TWOC. “It has to end up somewhere.”

That “somewhere,” as noted by a 2020 TWOC article that investigated the impact of mismanaged waste on rural China, could be contaminated streams in villages. It could be a Guangdong landfill that collapsed and killed 73 in 2015, or incinerators around the country that have failed to meet China’s emission standards, which are already 10 times as lenient as the US standard when it comes to dioxins.

China’s fast-growing e-commerce and delivery sectors have brought more demand—and more problems—for packaging. According to a 2019 report by Greenpeace and Plastic Free China, in 2018 alone, express delivery in China generated 9.4 million metric tons of packaging—consisting mostly of cardboard boxes, plastic bags, tapes, paper slips, and cushioning material. That number is projected to grow to 41.3 million in 2025.

Out of the 9.4 million metric tons, 85,180 are plastic materials which mostly end up buried (58.7 percent) or burned (37.2 percent). In addition to the high cost generated by these two methods of waste processing (705 and 511 yuan per ton respectively), as the report notes, TWOC’s 2020 investigation also reported on increased cancer cases and livestock deaths in a Jiangsu village near an incinerator, where high levels of airborne dioxins are documented.

From consumers’ needs to consumers’ hands

“No business would be so dumb as to bend themselves backward to over-package, if the consumers didn’t need it to some extent,” Zhang Zheng, the strategic advisor of Sixi Packaging Design, tells TWOC. The Xi’an-based startup has been designing innovative packaging for growing businesses since the end of 2017, with the goal of increasing product sales.

Ambrosial’s new yogurt, for example, has seen over 6,000 sales monthly on e-commerce platform Tmall. A 22-year-old woman in Xianning, Hubei province, who asks to be identified as Xu Zhenzhen, finds the new packaging adorable, albeit slightly wasteful. “If it comes at the same price as Ambrosial’s old packaging, I would definitely buy this new one,” she says, naming price, appearance, and quality as the major factors that inform her purchasing decisions.

Product safety concerns also contribute to overpackaging. E-commerce businesses interviewed by Greenpeace noted that viral videos of violent package-sorting on social media—showing delivery workers casually throwing packages around at the warehouse—have contributed to the mindset from both businesses and consumers that packing in layers is necessary to keep products safe.

Delivery workers often take liberty to add even more protections. A package sorter surnamed Sheng told People’s Daily in August 2021 that he usually smothers expensive and fragile items in layers of foam, paper, boxes, tape, or even wooden frames to avoid having to pay a fine of hundreds of yuan for broken products. “The delivery worker only makes a few yuan or even less out of one package. There’s no way we can afford the fine,” said Sheng.

Similar concerns rise in food takeout delivery, as a dish’s journey from restaurants to customers’ hands is fraught with opportunities for damage and contamination, including malicious tampering. “With the pandemic still around, careful packaging is necessary to put customers at ease when they eat,” a breakfast shop owner surnamed Li in Beijing told Worker’s Daily in 2020, “staples and cellophane wraps are musts.” Spilled soup or broken containers could lead to a bad review, which would be fatal to a family-owned restaurant.

Wang Kejing, who heads the plastic reduction program at Green Stone Environmental Protection Center, a Nanjing-based grassroot organization, is trying to allay food safety concerns by convincing deli businesses that less packaging is actually more hygienic. “We educate milk tea shops about how bacteria grow in drinks that sit out for too long, and train employees to advise customers to open the drink on the spot for the best experience, instead of packing it with an extra plastic bag.”

While food industry and delivery systems layer up plastic for the sake of protection, consumer product companies “resort to piling up materials to create what they believe to be ‘good experience,’ or ‘class,’” laments Sixi’s founder Ni Fei, citing the ornate boxes of mooncakes he receives from relatives, friends, and acquaintances around Mid-Autumn Festival.

The government is trying to limit how far packaging can go. The SAMR’s updated national standards spell out restrictions on layers of packaging that a product may have (three for most food and four for other products), the ratio of empty space to container, and the cost of packaging—no more than 20 percent of the retail price of the product. After a two-year transition period, substandard products will be forbidden from being manufactured or sold.

The continued life of packaging

But mandatory standards are just the start, believes Chang Xinjie, China’s National Vice Chair of the European Chamber’s Environment Working Group. “How do we encourage good packaging, and punish bad ones?” he points out. “Packaging that does meet the standard might still create environmental risks and waste resources, if not recycled well. Who should be responsible for the associated cost?”

Cainiao, the express delivery courier under Alibaba, one of China’s leading e-commerce companies, is working to cut down delivery packaging. In addition to collaborating with businesses—promoting specially-designed tapeless boxes, setting aside a “Green Market” section featuring green products, including ones that do not come with additional delivery packaging—Cainiao has consolidated the five information slips that it used to attach to a package down to one sheet only. “Just this one move helps reduce our carbon footprint by hundreds of thousands of metric tons a year,” Wang Haosu, head of Cainiao’s green initiatives, boasts in an interview with TWOC.

Starting in 2017, Cainiao has also been trying to create an internal system to reuse cardboard delivery boxes, with all Cainiao delivery stations around the country—about 100,000—accepting box returns. During Alibaba’s “Singles Day,” China’s biggest online shopping event of the year, on November 11, 2021, the company offered a carton of fresh eggs to every customer who brought in four used boxes.

According to a report released on Lieyunwang, an Alibaba-backed startup service company, this campaign drew in 4.8 million participants. Combined with its other green initiatives, Cainiao claims to have cut its carbon footprint by 53,000 metric tons from November 1 to 14, 2021. The report, however, does not disclose Cainiao’s total carbon footprint throughout Singles Day, while The State Postal Bureau registered a record-setting 4.8 billion packages delivered over the period from November 1 to 11 that year.

Despite initiatives, like Cainiao’s, that give some packaging immediate second life, most packaging materials find themselves in community sorting stations after they leave consumers’ hands.

Testing for community trash sorting in China started in 2000, and by December 2020, 46 cities had set up a basic trash sorting system in 86.6 percent of their communities, according to the Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development. These include Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, but also non-major cities like Tongling in Anhui province and Shigatse in Tibet Autonomous Region. Among them, Shanghai’s well-publicized program has become the poster child of community sorting in China, and saw 57.7 percent growth in the daily average amount of recyclables collected citywide in 2020.

Liu Chao, a middle-aged volunteer at a community waste station in Beijing’s Sanlitun area, tells TWOC he deals with 40 to 50 bins of trash a day, re-sorting misplaced waste and keeping the station clean—plenty to keep him and his wife busy from early morning to 7 or 8 p.m. “It’s impossible for me to correct everything,” he concludes as he rescues a cardboard box from the depths of a black bin meant for “other trash.” Selling these recyclables to a waste collector gives him an additional income of 40 to 50 yuan a day.

These collectors, often seen peddling their tricycles with plastic bottles, foam boxes, or flattened cardboard boxes piled high like wobbling skyscrapers, scavenge for these recyclables or buy them from residents, often retirees who make a hobby out of collecting, and then sell to recycling companies, often based in villages on the outskirts of the city. Domestic waste from different neighborhoods, as well as specialized waste such as used electronics, usually converge here and are further sorted by manual labor into different waste categories—such as paper, metals, and e-waste—for sale into various industries. According to Chang, the reliance on these “informal collectors” is an important factor setting China’s recycling system apart from that of Europe, which is more standardized and centralized.

The waste-sorting process is the link in the recycling procedure that Chang, also serving as vice president working on circular economy at Norwegian company Tomra Group, hopes to tap into. Technologies such as Tomra’s optical sorting machines can detect and separate different materials earlier in the recycling process. “If we can pick out more plastics from ‘other trash,’ we can funnel more of them into regeneration and reuse, instead of to landfills and incinerators.”

Chang believes that “the existing technology is mature enough that, with better implementation under the help of legislation, we should be able to solve about 80 to 90 percent of the plastic recycling problem we face right now.”

Full cycle problems need full cycle solutions

Li Bin, a professor researching circular economy at Donghua University in Shanghai, believes each part of the recycling process should find a way to talk with one another, rather than tackle their own weakness.

Issues at the recycling step need to be communicated back to the design and production of packaging, while “companies have an urgent need to communicate to consumers, letting them know packaging can be recycled instead of becoming trash,” Li explains. The Green Recycled Plastic Supply Chain Joint Working Group, an industrial chain collaboration platform Li cofounded, established a “2E Design” certification for packaging—“easy-to-collect, easy-to-regenerate”—that companies can print on packaging that meet the standards.

Laundry detergent brand Liby, for example, upgraded its two-material soft plastic packaging into a single-material one, earning it the first 2E certification in China. This allows it to print a logo shaped like the Chinese character “回 (return)” on the product. Leading takeout delivery company Meituan is also planning to push businesses on its platform to adopt 2E-certified plastic food containers.

“The problem, I think, is not ‘over’ packaging, but misguided packaging,” Sixi’s Ni says from the perspective of design. “The expression of ‘high-quality’ can be achieved through alternative ways—like text, or visual language.”

However, businesses, especially small-to-medium sized operations, don’t always find green initiatives easy. “Chinese companies tend to be strict on cost-control. When we promote the 2E certification, many businesses are unwilling [to adopt], because they are looking at extra costs,” Li reflects.

But he thinks it won’t stay like this forever, as companies will grow to realize what they lose over production cost, “they gain through what we call ‘intangible benefits,’ be it through their ESG [environmental, social, and governance], or something else.”

Alice Chen emphasizes the bottom-up role of consumers. “Your money is your vote. I don’t want my money to go to businesses that create overpackaging,” she says. She has only ordered takeout delivery once since her return to China last July, and her friends celebrate her birthday with secondhand items as gifts.

Chen recognizes, however, that she does not represent China’s mainstream consumers. Xu Zhenzhen, for example, finds it hard to keep sustainability in mind. “It just doesn’t come up,” she says, “Slogans like ‘clear waters and green mountains’ or ‘care for flowers and grass’ are everywhere in the streets. But when you see them so often, you stop really caring.”

Green Stone’s Wang suggests that the public messages from government or NGOs often try to portray sustainability as “good,” rather than “cool,” and wonders if politically correct messaging might antagonize people. “Personally, if you tell me something is good without completely convincing me, I won’t want to do it,” she says, “like we say ‘vegetables are good for you’ but still don’t want to eat them.”

Photography by Siyi Chu (褚司怡), additional photographs from VCG

What’s the Deal with Overpackaging in China? is a story from our issue, “State of The Art.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.