China’s domestic horror films still struggle to impress audiences

It was the most anticipated Chinese horror movie of the year (if ranking fifth in user votes on ticketing platform Maoyan is anything to go by), but Ning Ye, a self-proclaimed “horror enthusiast” residing in China, claims to be unimpressed by Case 1922, a period film released on February 18 about a phantom serial killer. “I don’t like Chinese horror movies. [They’re] not scary,” says the 33-year old, who watches up to half a dozen Japanese and Western horror flicks a month.

These thoughts are echoed by fans and industry specialists around China. “Major studios just ignore this genre by default nowadays,” Feng Zixuan, a producer with a major Chinese studio (who wished to use a pseudonym), tells TWOC, claiming to not have watched a Chinese horror film in 20 years.

Kai Ma, director of home-grown horror film The Possessed (2016), was paraphrased by online culture publication Poison Eye as saying that many young directors enjoy discussing horror films, but few express a desire to make them. From a peak of 69 horror films a year in 2016, domestic production has collapsed to just five in 2021, according to data collected by online film blog Sir Movies.

Homegrown horror films from the Chinese mainland get a poor rap in the country from both creators and viewers. The reasons are complex, stemming from a poorly understood prohibition by the China Film Administration (CFA) on violence and the supernatural, financial risk, the burden of audience expectations, and low status in the industry.

As a genre, East Asian horror has long been dominated by Japanese (“J-horror”) and later Korean (“K-horror”), which rose to prominence off the back of the international success of Japanese films like Ringu (1998) and Ju-on (2002). American audiences will recognize them by their remakes, The Ring (2002) and The Grudge (2004), which retained their cultural roots through the transfer to Hollywood, such as the character of yurei (vengeful ghosts in Japanese mythology). Similarly, the K-horror classic A Tale of Two Sisters (2003) became The Uninvited (2009), bringing this story based off a classic Korean folktale to a wider Western audience.

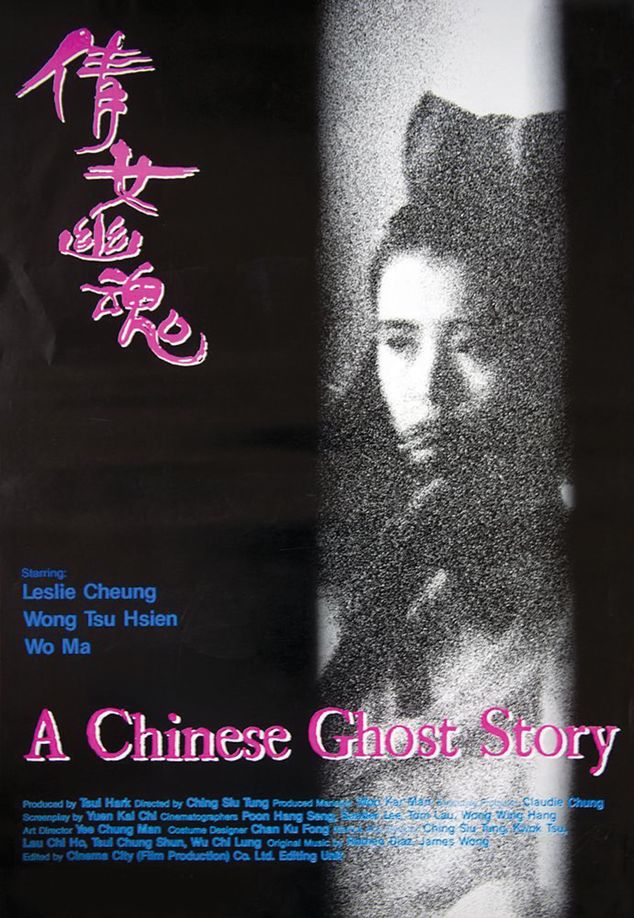

The Hong Kong horror industry has also done well, particularly in the 80s, spawning international cult hits like Mr. Vampire (1985), A Chinese Ghost Story (1987), and Rouge (1988). All had a distinctive homegrown flavor that often blended horror with comedy or kung fu, steeped in the trappings of Chinese ghost legends and traditional mythology.

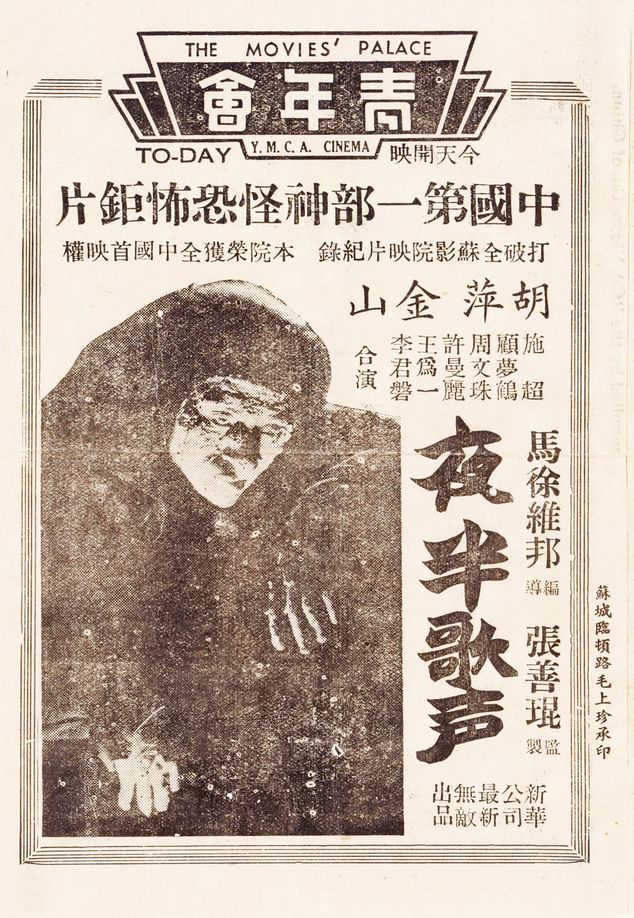

But the Chinese mainland’s crowning contribution to the genre hasn’t changed for 90 years: Song at Midnight (1935), a loose take on the 1925 film The Phantom of the Opera, is ranked first on Douban’s best-rated mainland horror films. Horror films for the past five years have either been too low-profile to merit a score on the platform, or else have been universally panned. Only four have managed to clear five out of 10 points since 2017.

Netizens have made a sport of mocking shoddy production values, tacky attempts at titillation, and general lack of scares. One such roast piece was posted on a film blog in 2017, and titled “10 Domestic Horror Films that Forgot to Pack a Brain, Or Else Think Their Audiences Are Stupid,” making fun of studios blunders like putting actors in revealing clothing to make their films sell.

In the past, both the Kuomintang and the Communist Party of China governments classified ghosts and devils as “superstition,” making horror stories a backward enemy of modernity. The 1930 Film Inspection Law decreed films that “spread superstition” could not be screened. A 1934 report from the Central Film Inspection Committee was more explicit, defining its first mission as abolishing “films featuring ghosts and spirits.”

Nevertheless, the law’s vague wording and uneven enforcement (as the ruling Kuomintang was fighting both the Japanese and the Communists at that time) allowed horror to thrive. Shanghai, the hub of cinema at the time, produced many gothic offerings in the 1940s, with titles like A Windy Night with No Moon (1947), and Haunted House No. 13 (1948).

But most of these films have long been lost, and Shanghai’s horror productions completely dried up after the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949. From this point on horror films were all but absent from the mainland, as the PRC’s first film regulations, issued by the Ministry of Culture in 1950, ordered film editors to cut out anything “superstitious,” or the film could be banned and prevented from public screening. Scripts had to be vetted at numerous levels both within studios and government departments before being approved to film.

But this didn’t stem demand—in a 2011 paper on ghosts and censorship, Professor Laikwan Pang of the Chinese University of Hong Kong noted audiences were attracted to many anti-superstition films between 1949 and 1976 precisely because of the supernatural elements the film was meant to condemn.

The reform period of the 1980s saw the first attempts at contemporary horror films, such as The Head in the House (1988), about a gruesome science experiment involving a disembodied head; and The Lonely Ghost in the Dark Mansion (1989), a gothic work about a large house with dark secrets.

From 2005 on, there was a steady stream of titles in production, some of which earned big at the box office. Mysterious Island (2011) hauled in 89 million yuan, while Raymond Yip’s The House That Never Dies (2014) gathered a still-unmatched 400 million. Investors flooded the scene, betting on cheaply-made horror as a quick way to turn a buck.

Films were churned out quickly, often lifting their plot-lines directly from the pirated Korean and Japanese titles that were showing in underground cinemas.

Promotion posters would list fake awards and nominations, or else outright lie about the nature of the film—Sir Movies, noted at least four productions claiming to be “China’s first true ghost film” between 2011 and 2017. Around 2017, audiences cottoned on to the scam and stopped visiting cinemas, leaving almost no horror films to gross more than 10 million yuan.

Decline in interest is combined with increasingly strict oversight. The Film Industry Promotion Law of 2016 is a step up from previous regulations governing the way films are screened. It sets out the processes for vetting films (also covering online films for the first time) and penalties for failing to comply: fines in excess of 250,000 yuan for the screening or streaming of any film that fails to get approval from the regulator (the CFA for domestic films since 2018, the China Film Group for foreign imports). Films are still vetted according to standards issued in 2008 that restrict “murder, violence, terror, ghosts, and the supernatural.”

New media is no exception. In 2017, the China Netcasting Services Association, a trade association registered under the government, released guidelines calling for industry self-regulation, and warned producers against adding “excessive horror, psychological pain,” and “uncomfortable pictures, lines, music, and sound effects.” That means non-supernatural horror—think The Texas Chainsaw Massacre—is also subject to rules around violence and negative portrayals of society.

Much of these guidelines are a matter of interpretation, left to the individual regulators screening the film. Pixar’s animation Coco (2017) was filled with ghosts and is themed around Mexico’s Day of the Dead celebrations, but was waved through with minimal delay. According to publications like Jiemian and Forbes, it was rumored that members of the Chinese Film Bureau had been deeply moved by the film, and admired its promotion of filial piety in its veneration of past generations.

But other productions have been hard hit. The Possessed (2016), a low-budget indie horror, which had won the Best Artistic Exploration award at China’s FIRST International Film Festival, was given approval for release in March 2018. But a few days before release, it was cancelled owing to “technical issues” (industry shorthand for regulator displeasure).

The uncertainty of how hard it will be to get approved means domestic horror has resorted to numerous rational explanations to skirt the “ghost ban,” like hypnosis (The Great Hypnotist, 2014), swamp gas (The House that Never Dies 2, 2017), LSD (The House that Never Dies, 2014), psychosis (Delusion, 2016), and the classic “it was all a dream” fallback (Guesthouse of Horror, 2012).

Fans also pile on pressure, as hard to placate as any government censor. Last year, Malignant, an international blockbuster with a budget of 40 million US dollars by well-known Australian director James Wan, became the first R-rated horror movie to obtain approval from the CFG. But having the CFG’s blessing meant the movie’s official Weibo account had to reassure fans, pointing out any cuts made were under the supervision of Wan himself, urging people to support the legal version and not the “large number” of pirated versions of the original springing up online.

But the fact Malignant was approved proves top-tier horror films are not a lost cause. Online streaming platforms like iQiyi and Tencent are investing in wangda (网大), or e-movies, which skip cinema release and go straight to online streaming platforms. The e-movie model often pays producers upfront, benefitting horror by removing some of the financial risk of relying on box office alone.

Over the past year, three online horror films with a distinctly Chinese flavor have received good reviews. Legend of Xing’anling Hunter (2021), starring veteran TV drama actor Shang Tielong, has already racked up 150 million views on Tencent video, and employs the novel workaround of revealing monkeys, rather than ghosts, as the actual cause of the strange occurrences around the village. Impermanence (2021) draws on Tibetan customs and funeral etiquette, and Town of Ghosts (2022) adopts a flavor reminiscent of the 17th century horror anthology Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio, while ultimately demonstrating the darkness of the human heart is more frightening than any ghost.

Two feng shui masters discover dark secrets in a mysterious town in the online horror film “Town of Ghosts”

All three echo what film studies Professor Li Zeng of Illinois State University characterized in a 2009 paper as mainland horror’s “aesthetics of restraint,” necessary to placate authorities. Such restraint favors slow-burn mystery and atmosphere, evoked by the Tibetan rituals in Impermanence. Overt gore is avoided, and horror elements kept in check by genre mixing—from the fantasy-adventure feel of Legend of Xing’anling Hunter to the more straight-forward suspense narrative of Town of Ghosts.

Other avenues are also presenting themselves: Animated violence is harder to police, and with the CFA explicitly seeking to diversify the animation sector with its newest five-year film plan (2021 – 2025), several animated horror shorts have surfaced in recent years, starting with the impressively gory webseries Zombie Brother in 2013.

But whatever the reason, it is far from obvious when Chinese horror will have its next box office hit, and it’s unlikely that Song at Midnight will be unseated any time soon. To China’s horror fans, that might be the scariest thought of all.

Four Must-See Movies

Lighting Up the Stars

“You see that chimney? That’s your grandmother roasting, turning to smoke. Floating up to heaven, no more, vanished,” barks a grown man at an 8-year-old girl, who understandably bursts into tears. “You won’t see her ever again, do you understand?” Lighting Up the Stars is the strange and heart-wrenching story of an undertaker recently released from prison, Mo Sanmei (Zhu Yilong), whose heart is slowly softened when he adopts spirited orphan Wu Xiaowen (Yang Enyou), who is grieving the death of her grandmother. This flick promises superb acting from Beijing Film Academy graduate Zhu and child star Yang.

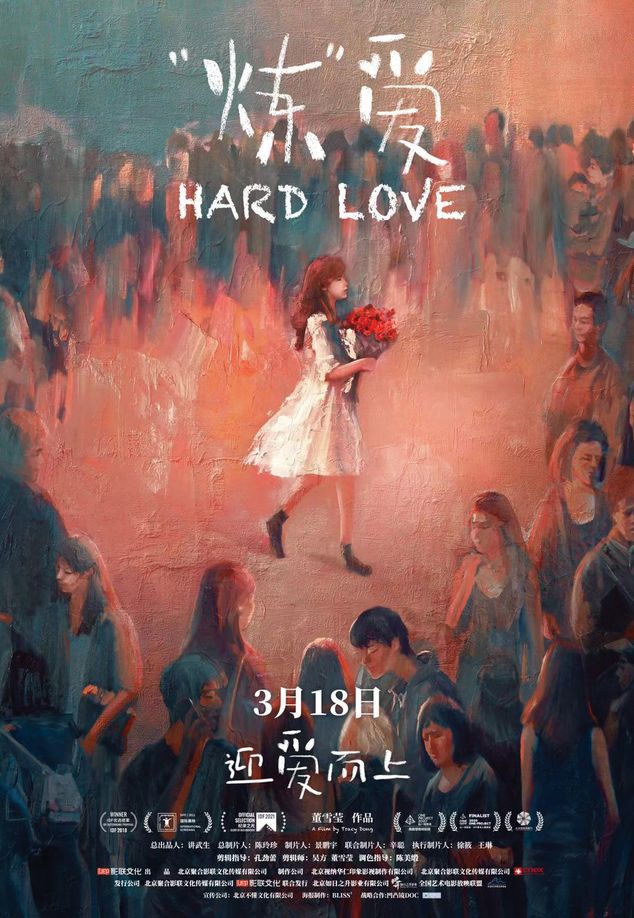

Hard Love

Many in China now choose to delay marriage until the storms of competition for jobs and housing have subsided. But finding a happy family life can be another battle all of its own. In the documentary Hard Love, up-and-coming young director Dong Xueying explores the love lives of five young women living in Beijing in very different circumstances, all of whom are still single past the traditional marrying age. Dong filmed her subjects from 2018 to 2019, filtering 300 hours of footage down to one-and-a-half.

The Chanting Willows

On the surface, this film by Dai Wei is a tortuous love triangle, following two female opera singers whose friendship is rent asunder when they compete for the same man. But it comes with cultural pedigree, adapted from a story by Mao Dun Literature Award-winner Wang Xufeng. The Chanting Willows is bedecked with all the beauty of Hangzhou’s famed West Lake and Yue opera. Indeed, this local form of opera is the fourth star of the show: The film takes care to immerse the viewer in the Yue opera world and features over 20 minutes of singing.

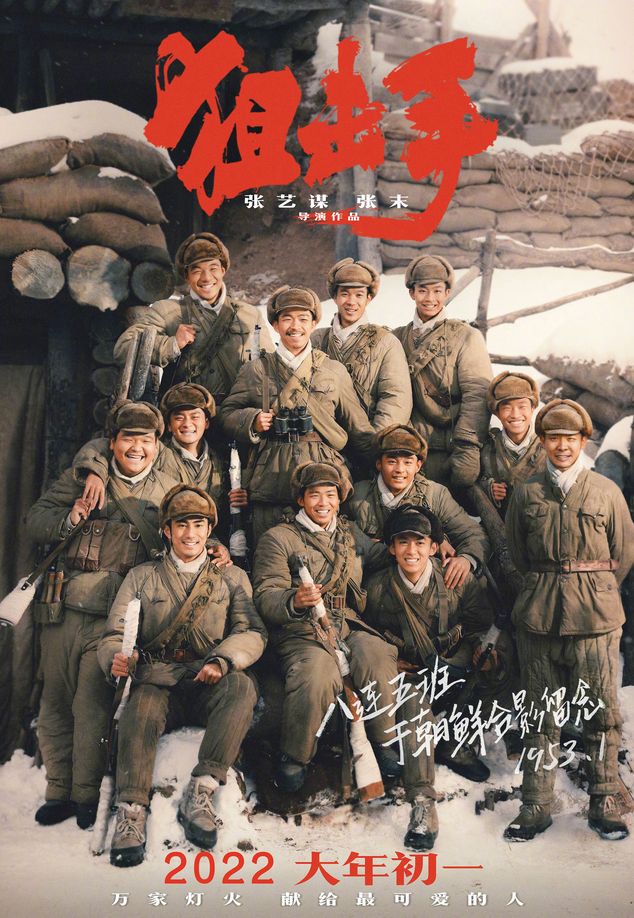

Snipers

China’s latest patriotic offering is directed by Zhang Yimou, and follows the brave actions of five Chinese snipers during the Korean War, as well as their bullets—the camera tracking crack shots all the way to the foreheads of their American targets. The film has been praised in Douban reviews for its heightened realism by using unknown actors. Other comments compare the bombastic caper to major patriotic blockbusters like Operation Red Sea. – Alex Colville

What Spooked China’s Horror Film Industry? is a story from our issue, “State of The Art.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.