Do government regulations mark the death sentence of the role-playing murder game industry?

Holding a booklet in hand, Baishi sits at a table, shedding tears of sorrow as she discovered the truth about herself: She wasn’t an orphan at all, but rather a daughter of a poor rural family who ran away from home after being unfairly accused of theft at school and repeatedly fighting with her parents. Oh, and she had leukemia.

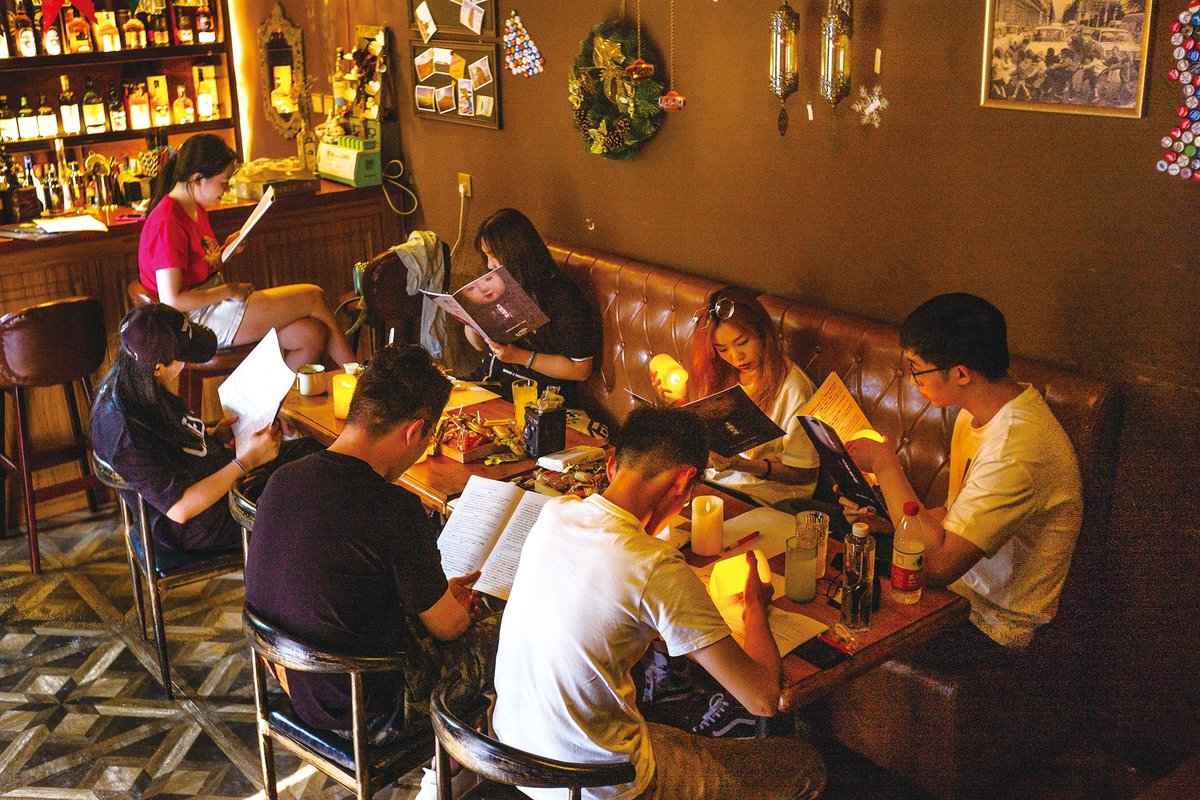

Don’t worry, Baishi isn’t going to die—when the lights come back on at the end of the night, Baishi, who asked TWOC not to use her real name, melts back into her regular identity: a 26-year-old Beijing resident and fan of jubensha (剧本杀), literally “scripted kill,” a type of role-playing game with over 9 million players in China. On this night, Baishi and six friends have spent about four hours locked away in a Beijing mall acting out Bunnies Are Good, a script about six young leukemia patients and a father who lost his daughter to cancer.

Based on Clue, a classic board game developed in 1943, jubensha also takes inspirations from Murder Mystery, a live action role-playing (LARP) game from the 1980s, in which one player is secretly assigned the role of a murderer and the guests must figure out the identity of the killer by following a script and looking at clues.

In China, murder mystery games took off with the release of a hospital-themed deduction-based board game called Death Wears White in 2013. However, it was the reality show Who’s the Murderer, which premiered online on Mango TV in 2016, that was directly responsible for jubensha’s current format and popularity. On the show, a number of celebrities got together and had to solve a “crime” by rummaging around for clues, which started a trend and spawned the rapid creation of new scripts.

Today, jubensha is typically played by a small group in an indoor venue—either sitting around a table as in a tabletop game or, as a newer version, in an “immersive” environment that mixes role-playing with “escape room,” requiring players to interact and search of clues in several rooms. Players are given booklets outlining their characters’ backstory and notable traits, and must work together to solve a problem in the script, usually (but not always) a crime. A game host narrates the script, occasionally handing out clues and inviting players to interact with one another; in the immersive version, there could be other staff members playing supporting roles.

In major cities, a tabletop jubensha session costs about 200 yuan per person and can last four to five hours, or even a whole night, while the immersive version starts at 300 to 500 yuan. To Baishi, playing jubensha is to “pay hundreds of yuan for a taste of a different life.”

Since last July, when she picked up the game as a distraction from her exhausting job, Baishi has played more than 50 different roles: She has been a wife murdered by her husband, a psychologist grappling with her own mental demons caused by childhood trauma, and a woman trying to resolve a misunderstanding with her best friend and her ex-boyfriend a decade after their separation in high school.

In a 2021 article by Tang Yicheng, the vice secretary of the Chinese Psychological Society’s working group on popularizing psychology, the author claims that role-playing games help players acquire the qualities and traits of the character they play in order to achieve “personal growth”—a form of “faking it ’til you make it.”

Another 2021 article by Yi Psychology, an online content platform focusing on mental health, asserts that role-playing games allow players to transfer their emotions and expel negative feelings. “You can experience a variety of emotions,” says Baishi, “like why someone would kill, or why someone might choose not to forgive a friend.”

A 2021 report by e-commerce platform Meituan estimates the value of the jubensha market that year at over 15 billion yuan. Over 70 percent of players are under the age of 30, and over 40 percent of them play the game more than once a week. Some hotels and theme parks are also jumping on the bandwagon to set up immersive escape rooms and jubensha venues to tap into the emerging bonanza.

Seeing the market potential, data analyst Lu Mingfei, who asked to go by a pseudonym, spent over 500,000 yuan to open a “script-killing shop” in Beijing last September. But the venture wasn’t as easy as he’d imagined. Apart from buying rights to the scripts, which cost around 300 to 500 yuan each, Lu has to source scripts that would appeal to his customers, usually in offline trade fairs or from online script-publishing platforms like Heitan Youpin.

He then must work with his staff to review the script for feasibility and plot-holes, prepare props, and set up the room for each session. However, revenues have fallen short of Lu’s expectations. He confesses that the shop can just barely break even, due to the number of competitors and high cost of renting his venue, paying employees, and setting the stage for each session.

To compete, some scriptwriters and jubensha shops have added violence, horror elements, and even sexual content to attract players. Last September, a report from China Comment, a magazine affiliated with the state-run Xinhua News Agency, described a scene of five high-schoolers sitting next to two coffins, screaming while the host read from a script about a ghost hunting people down in a remote village, and concluded that the industry lacks supervision over script content and venue-management.

In the same month, news site The Paper reported that a 21-year-old college student in Hangzhou, Zhejiang province, is “addicted” to jubensha, allegedly threatening to kill his mother when she tried to prevent him from staying up late to play the game. According to his psychiatrist, Dr. Su Heng, a local hospital sees patients suffering from depression, anxiety, and other mental health problems due to jubensha every month. Dr. Su believes that the immersive environment and emotional highs of jubensha make it hard for players to reintegrate into regular life, and the violent content can trouble youths.

Last November, Shanghai Municipal Administration of Culture and Tourism became the first government body in China to attempt to regulate jubensha. New draft guidelines for the industry stipulated that jubensha scripts cannot contain violent, pornographic, drug-related, or criminal content, or promote superstition, and that jubensha businesses cannot “harm the mental health of employees or consumers.”

Beijing has no similar regulations, but Lu says officials from the municipal culture and tourism bureau conduct sporadic inspections of shops like his to check for violent, horrifying, or pornographic scripts, and give suggestions to protect minors from exposure to harmful content. “They will ask you to pull [inappropriate scripts] off shelves,” says Lu, whose shop allegedly has never failed any inspection.

Xiao Jie, a game host in Beijing who has facilitated over 200 jubensha sessions, has seen some risqué content since she entered the industry last March, but believes it is in the minority. She explains, “We test and edit the scripts to make sure there is no harmful content for users each time the script comes to us.”

Jubensha enthusiasts also feel the media has amplified extreme cases and scapegoated the game for issues of more complex origins. “Some people may already have psychological problems that you don’t notice in daily life, and jubensha is blamed after they play one session of it,” says Xiao Jie. Baishi agrees: “Let’s say both you and I watch a movie, and I kill a person afterward, but you do nothing. Is the movie to blame or myself?”

For scriptwriters, a more pressing problem may be the rampant piracy in the nascent industry. Unlike books or other print publication, there is no government-assigned serial number for jubensha scripts. “Some writers just copy-and-paste lines from detective novels, games, TV series, and movies in their script,” says Duo Chunheng, manager of an online platform that allows users to rate jubensha scripts, “or replicate the plot of novels, dramas, and even other jubensha scripts.”

Besides associated moral issues, Duo notes that plagiarism also decreases the value of jubensha scripts and discourages creativity, making innovation less profitable for writers and jubensha shops. “These days on Taobao and other e-commerce platforms, you can buy over 2,000 sets of digital scripts at only 19.90 yuan,” he says.

These concerns, though, are not likely to deter ordinary enthusiasts like Baishi, who’s getting ready to play another round on the weekend when TWOC speaks with her. “By playing these roles, I’ve experienced team spirit, friendship, romance, and family affection,” she says.

“I’ve also gained a lot of good friends in this circle,” she adds, noting that jubensha is more than a virtual experience. The six friends whom Baishi played the leukemia-patient script with all met through jubensha, and they’ve mushroomed into a large group on WeChat where they organize weekly role-playing sessions, as well as meals, hikes, and other outings.

When TWOC checked in on one such WeChat group on a Tuesday, the members were in a discussion on whether it’s better to play the murderer or innocent bystanders in the script. “There’s no fun in it; you already know the answer,” one player declares, while another argues, “It’s nice to be able to have a ‘God’s eye’ view of the game.” A third player interjects, half-jokingly, “Maybe the murderer won’t know they’re the murderer. Maybe [in the script] they can develop amnesia.”

Photographs from Baishi, Xiao Jie, and VCG

The Business of Murder: Regulations Hit Role-Playing Murder Mystery Games is a story from our issue, “Sports for All.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.