An online art exhibition calls attention to the infamous “chained woman” case in eastern China, despite repeated censorship

In early February, when he heard news that his 2007 independent film Blind Mountain was once again being widely pirated around file-sharing and illegal streaming sites in China, director Li Yang decided not to sue. “I should be charging copyright fees,” the 62-year-old filmmaker wrote on WeChat, “but in order to save trafficked women in China and fight the evil of human trafficking, I won’t. Everyone is welcome to forward and watch [the film].”

The 15-year-old film about human trafficking, which was shortlisted at Cannes, was back in the public eye due to a real-life horror that mirrored the plot of the movie: While livestreaming about a man with the surname Dong, who had eight children and lived in a village in Fengxian county in the city of Xuzhou, Jiangsu province, a group of vloggers accidentally found the mother of these children chained inside a shed behind the family home, with only thin clothes to protect her against the cold.

The discovery of this woman, believed to be a victim of human trafficking and struggling with mental illness, prompted others to come forward with stories about female trafficking in Fengxian and other regions of China, with hashtags related to the incident becoming some of the most hotly discussed topics across social media platforms. The topic has generated an estimated 5.2 billion views on microblogging site Weibo at the time of writing, second only to the Winter Olympics.

Chinese artists across disciplines have also responded by speaking out against human trafficking through their creative works, though they’ve had to fight censorship every step of the way. On February 6, Chinese-American novelist Yan Geling published an article “Mother, Oh, Mother!” expressing her anger over the Fengxian case and society’s valorization of motherhood, which was removed by WeChat shortly after it started spreading on the messaging platform and other Chinese social media, with WeChat even blocking users from sending screenshots of the article.

Li gave an interview with independent blogger Liulang Nanfang (“Wandering the South”) in mid-February saying Blind Mountain actually toned down many of the harrowing stories the crew heard while making the film, stating “If there’s just one person who saved their sisters from tragedy because they watched my film, it would be more meaningful than if the film had made billions”—but a similar interview with the director on another account was removed by WeChat on February 6.

On February 3, a collective of more than ten Chinese artists, novelists, and poets put a call out for an online exhibition named “Breaking the Chain,” asking for submissions of creative works in any format to raise awareness on the Fengxian case and the trafficking of women in China. “For us, it was an emotional response at first,” one of the exhibition’s organizers, who only wanted to be identified by her surname, Zhang, tells TWOC.

“A day or two after the news broke, we thought it was time to take some action,” she says. “The reason why [this woman’s story] angered the whole country was because it was too tragic. Nobody who saw her face could tolerate leaving her to her fate.”

The organizers received over 100 pieces of artwork in the first two days after they announced the online exhibition, and chose the best-quality works to publish on Zhang’s public WeChat official account on February 8. These included paintings, installations, photography, poetry, and short fiction from 27 artists and writers, published in the format of a WeChat article. They included both original works inspired by the Fengxian incident, as well as previous works by the artists that were relevant to the exhibition’s theme.

Guo Zhen, an internationally renowned feminist artist and a survivor of domestic violence, heard about the online exhibition through friends, and sent three images of her previous work. “This is barbarism and slavery,” Guo, who says she wept when she heard the news from Fengxian, tells TWOC.

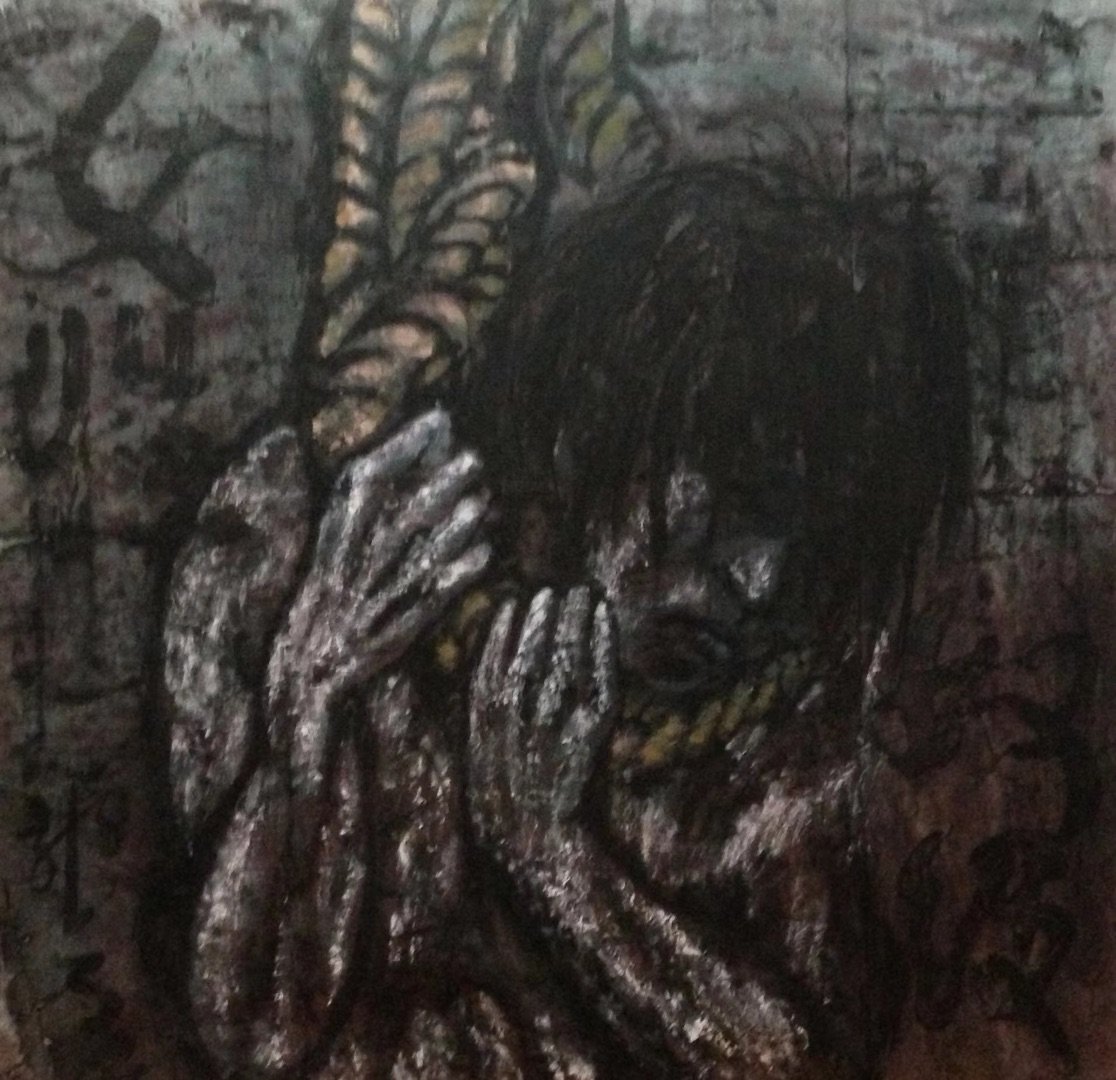

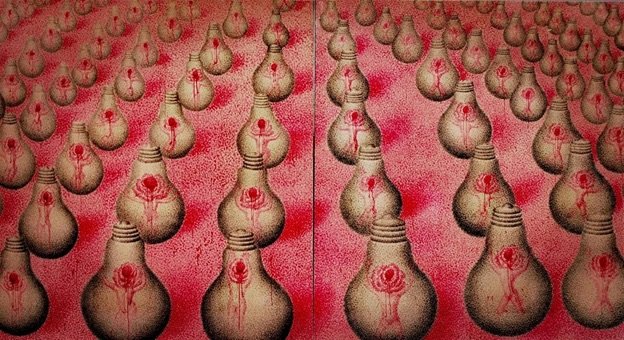

Guo’s works, all made before the Fengxian incident, include a black-and-white painting of a chained woman in agony called “Untitled,” and two installation pieces: “Her in Swamp” is a sculpture of a woman’s breast inside a plastic globe that is filled with liquid and surrounded by scorpions; and “Punching Bags,” made up of several sets of heavy sandbags hanging from the ceiling, each covered by female breasts made of colorful cloth. “Women are a vulnerable group that get arbitrarily attacked like punching bags, but women’s power will also suffocate the patriarchy,” Guo writes under the latter work in the WeChat article.

However, the exhibition article was soon deleted by WeChat, which has also removed a number of other posts about the Fengxian incident. Guo’s personal WeChat account was also permanently suspended after she shared the exhibition article and other content showing support for the Fengxian woman. The artist, who has been living in the US for about 30 years, has been unable to message her family or friends in China on WeChat over the last two weeks, though she can still see their “Moments” updates.

Zhang then migrated the exhibition to “Art Express,” a blogging platform under art news portal Artron, where it attracted 40,000 clicks in about two days. “We posted a second edition of the exhibition [featuring different artwork] a week later, and the response was also not bad,” she says.

On February 23, however, the Jiangsu provincial authorities released the fifth official statement on the Fengxian case, following previous statements from the county and Xuzhou city governments. Early statements had alleged there was no trafficking involved, that the woman was a “homeless” person picked up and “given refuge” by the Dong family, and that she’d married Dong of her own free will. The latest statement identifies the woman via DNA testing as Xiaohuamei from Fugong county of the Nujiang Lisu Autonomous Prefecture in Yunnan province, who went missing in 1998, and adds that she had been sold at least twice before being bought by Dong’s father in 2000.

Since this statement came out, “public discussions have been tightened up, and we can’t see the content [of our art exhibition] anywhere [online] now,” Zhang tells TWOC.

She also says artists like her are not convinced by the official explanation. “Ask any artist in China, especially those who do sculptures, and they’ll tell you that [Xiaohuamei and the chained woman] have different bone structures [in photographs]: The distances between the eyes are different, the jawbones are different, and the structures around the mouth are also different.”

Other internet users have also been questioning the official conclusion on both the woman’s real identity and promises of accountability for the local government, the traffickers, and the family members and neighbors in Fengxian who were complicit in confining the woman and falsifying her records. The latest update from Jiangsu states that the authorities have arrested Dong and the alleged human traffickers involved in this case, punished 17 local officials in Fengxian with dismissal and investigation, and sent the woman to a local hospital for medical and psychiatric treatment.

Zhang calls for a repeat of the DNA test by a third-party institution independent from the Jiangsu government. Meanwhile, the artists plan to continue speaking up about the issue within their own community. They are working on a third edition of the art exhibition, but are still struggling to find an online platform to host it on.

Zhang says the artists might also write articles to keep questioning the official verdicts, using their perspectives from visual arts. From how she sees it, the battle is not done. Referring to a recent photo showing the woman in the Fengxian case wearing a plastic wristband connecting her to her hospital bed, for which netizens are once again demanding an explanation, Zhang says, “I think [the woman] has not yet been totally rescued, because she is still in Xuzhou. She is being treated in the hospital, but her hand is still chained.”

Images courtesy of Guo Zhen and Zhang