How picture newspapers in the early 20th century reflected changing views on freedom and love

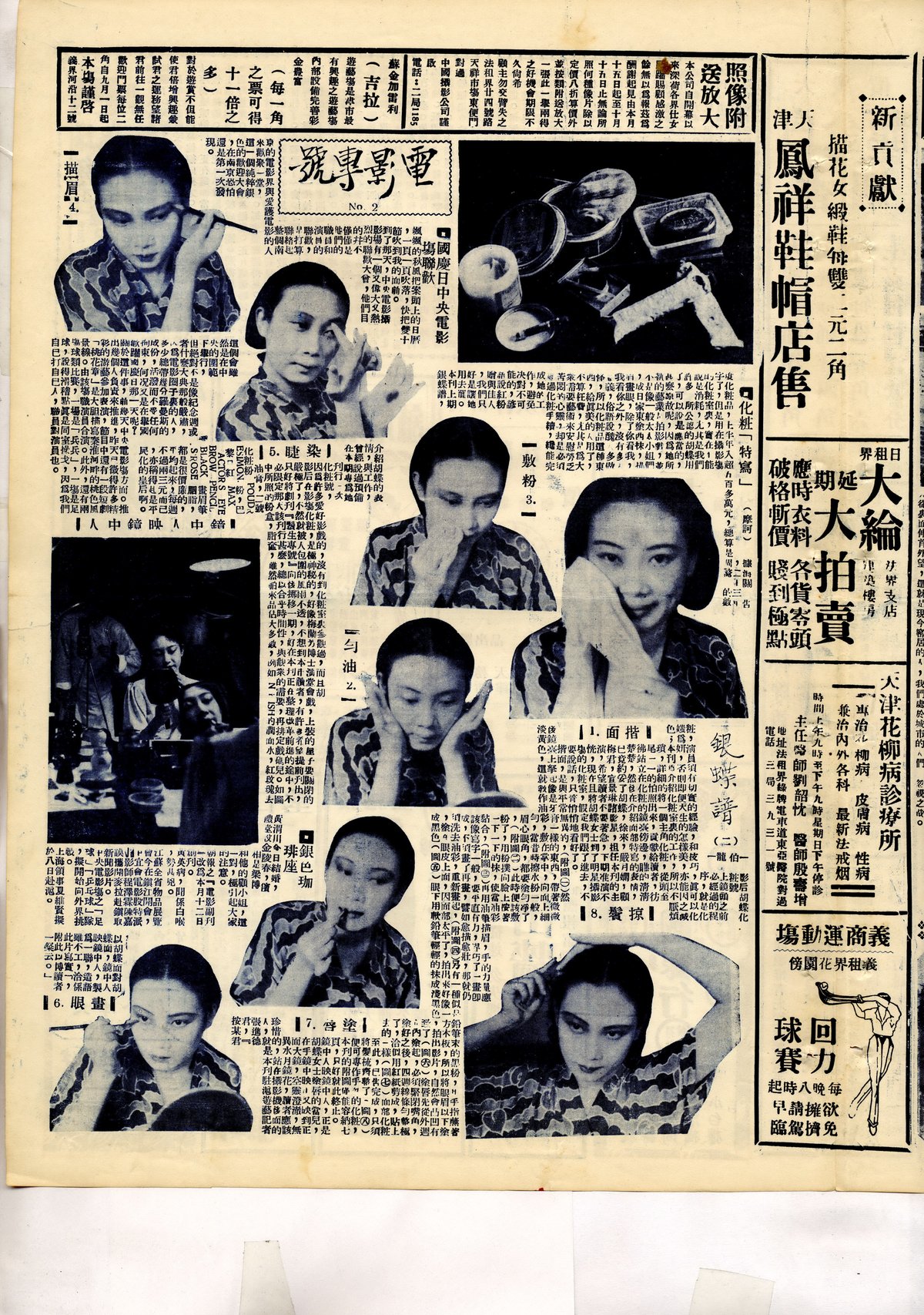

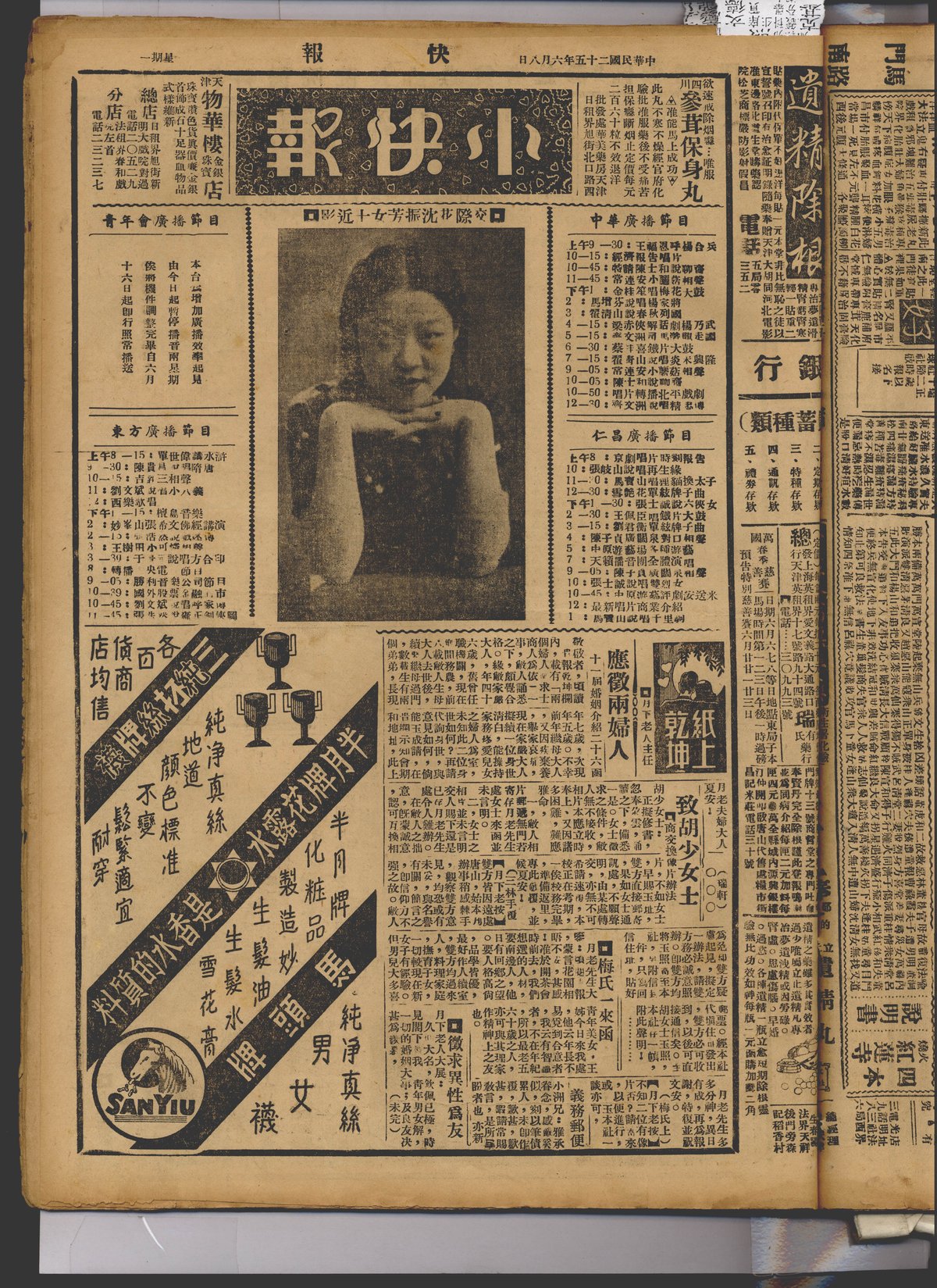

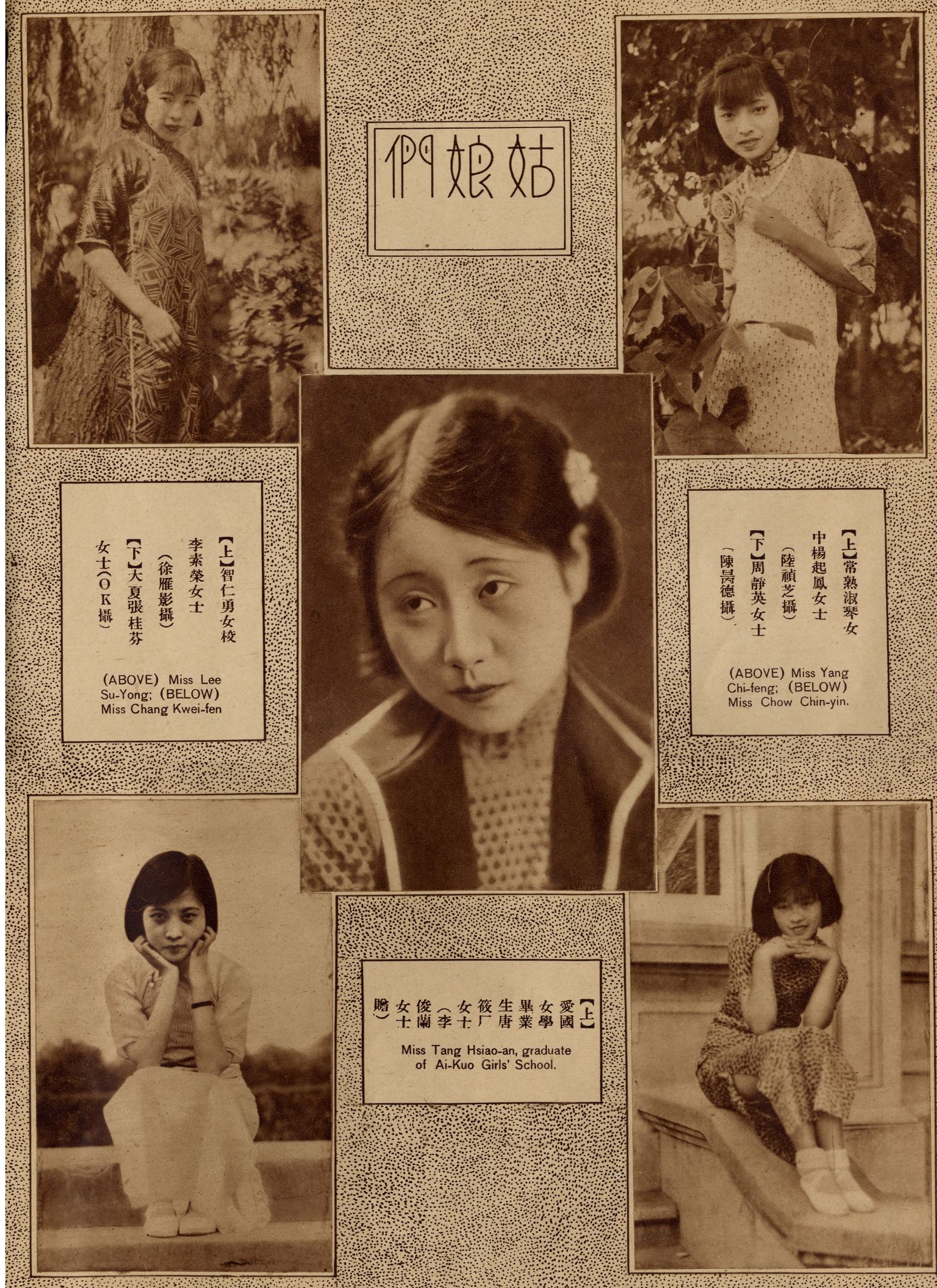

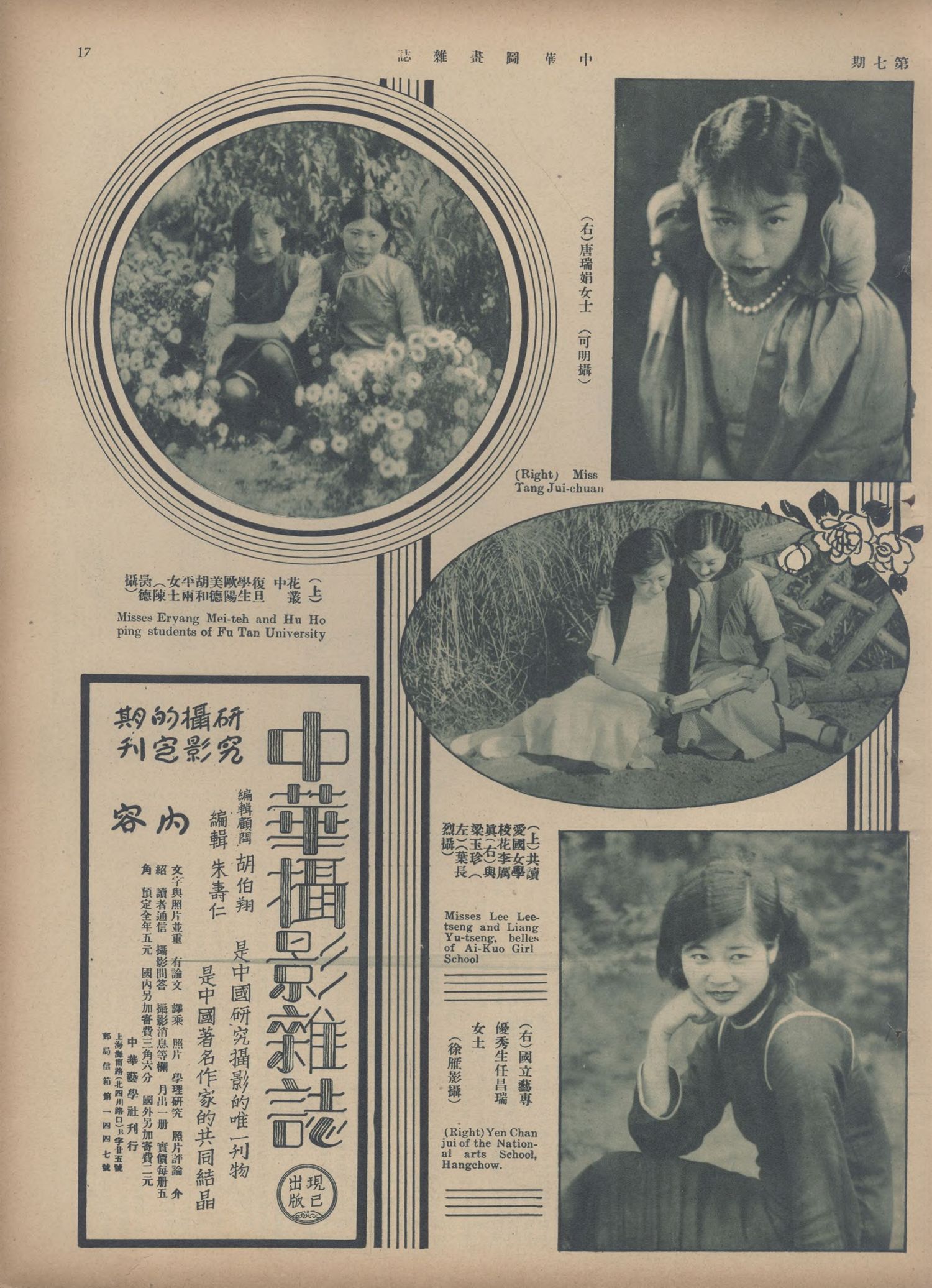

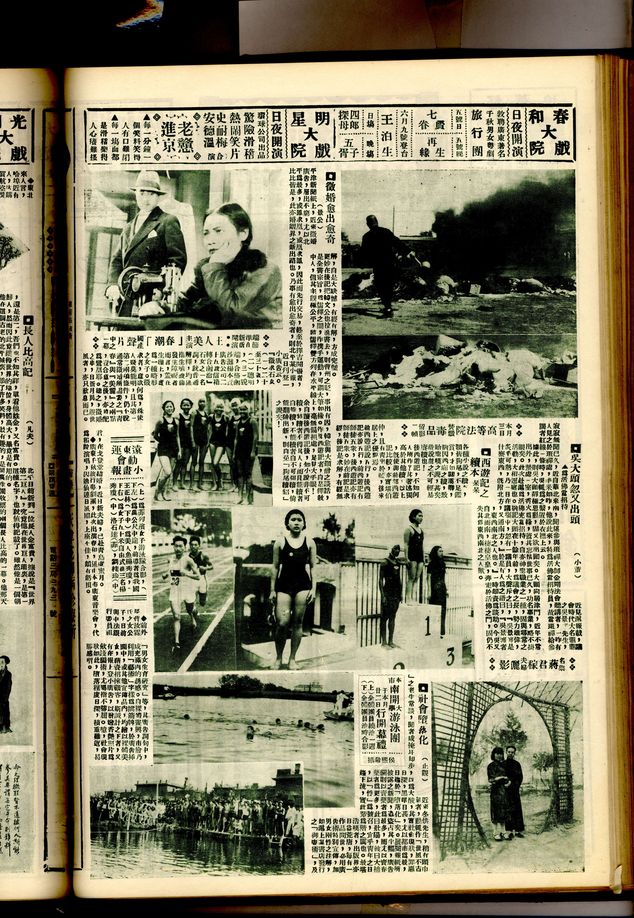

Although now largely disappeared from history, “pictorials” were a common source of information during China’s Republican period, from 1912 to 1949. These were widely circulated picture-based newspapers, typically featuring large numbers of photos and cartoons paired with close-set characters about the size of ants. They were essentially the WeChat public accounts of their time.

In 2000, Zhou Licheng, a researcher at the Tianjin Municipal Archives, found 10 old pictorials at a secondhand book store. They opened for him a new window into the entertainment and public life of the Republican period.

Today, Mr. Zhou walks us through his new book, Marriage Stories from Old Pictorials, using the stories of three Republic-era women to uncover a past world of love, freedom, and rebellion.

-1-

A brief history of pictorials

1875—

China’s first pictorial was a religious publication out of Shanghai, Children’s Monthly. These early pictorials were printed in large type on thin, translucent paper. Their illustrations have a strong hand-drawn character.

Zhou Licheng: In reality, these papers at the time were only “pictorials” in name. They were light on pictures, but what they had was very colorful. Working in the archives, I was used to reading bureaucratic reports and government documents, so when I encountered these readable pictorials, packed with gossip and anecdotes, I was sucked in.

1920—

The well-known journalist Ge Gongzhen (戈公振) founded the Pictorial Times, the first publication to primarily feature photos. It was printed on coated paper, which has held its color well and feels just like modern magazine paper.

Zhou: This opened up the golden age of pictorials—1935 was even designated the “Year of the Magazine.”

February 1926—

The first issue of the Good Friends Pictorial featured China’s first screen star, Hu Die (胡蝶), on the cover. Holding fresh flowers and smiling sweetly, her image left a deep impression, making Good Friends a major publication almost overnight.

Zhou: There were many kinds of pictorials in the 1920s. The content generally focused on celebrity stories and society gossip, as well as reports on fiction, movies, operas, and other cultural content. It had a finger on the pulse, and was sometimes even considered indecent.

For example, in Tianjin there was the Fengyue Pictorial, full of profiles of prostitutes, dancers, and hostesses: their features, hometowns, personalities, and so on. It went on to highlight the patriotism of these women and their appeals against societal injustice—all told, a vivid and thorough accounting of their lives.

-2-

Outlandish courtship ads

There was another distinct phenomenon in the pictorials of that era: the appearance of large numbers of matrimonial ads from young men and women.

The Republican period was marked by ideological shifts. This was particularly striking when it came to the issue of marriage.

For example, Peking University president Cai Yuanpei (蔡元培) posted a matrimonial ad in 1900. He listed five criteria for his ideal marriage: The woman must not have bound feet; she must be literate; the man must not take a concubine; the woman may remarry after the man’s death; and a couple may divorce if they do not make a good match.

These conditions appear to have been ahead of their time. In contrast, most of the marriage ads posted by men upheld the expectations set out in Confucian ethics.

Zhou Licheng: One of the primary standards for women was their appearance. Second was that they be obedient and defer to their husbands in their decisions.

The marriage ads of the time were all over the place. My sense is that some people weren’t really seeking a partner, but rather attention.

For example, on May 21, 1926, this ad appeared in Shen Bao (or Shanghai News):

I am 25 years of old and hail from Wuchang, Hubei. I hold a Bachelor of Arts degree from a famous American university. I am currently a professor at a technical college, earning 300 yuan a month, in possession of family property. I am seeking a sympathetic woman as my life companion. Candidates must meet the following requirements:

1. Between 18 and 23 years of age;

2. Clean, with no pockmarks on her face or spots on her body;

3. Must bear three children within three years;

4. Please include a recent nude photograph with your application.

Logically speaking, the photo studios of the time could not have offered such a service, and next to no families owned a camera. So nobody could have responded to such an ad.

On the other hand, marriage ads posted by women were less common—perhaps just one for every ad posted by men. Women of the time had similar criteria for men as they do today, emphasizing occupation, wealth, appearance, and interests.

But Mr. Zhou’s book also mentions a few women who had alternative requirements.

For example, in a 1928 issue of Shen Bao, a young lady from an official family had this request as to a man’s origins: “Aside from Shanghai, any province or county is acceptable. Willing to travel to provinces as distant as Yunnan or Guizhou.”

It appeared that this woman’s father had warned her against the fickleness of Shanghai men before he died, and advised her to find men from other regions.

The courtship process was rather complicated for women. After the initial recruitment, they would spend a month interviewing and deliberating, finally exchanging photos with a suitable match by mail. If the pairing didn’t work out, each side would remain discreet about the experience for the sake of her virtue.

Zhou Licheng: In the 20s, very few women were free to date. Most of them didn’t stray from the confines of their homes; marriages could be proposed without the man or woman ever having seen each other. One-on-one conversation and hand-holding were impossible.

In those days, a woman’s purity was the highest priority.

But men were free to visit brothels and take concubines. Even though gender equality and freedom of marriage were proposed in the wake of the May Fourth Movement, those ideas were little more than slogans.

-3-

A Republican Romeo and Juliet

Tragic love stories were a staple in the newspapers of the time—the sadder, the better.

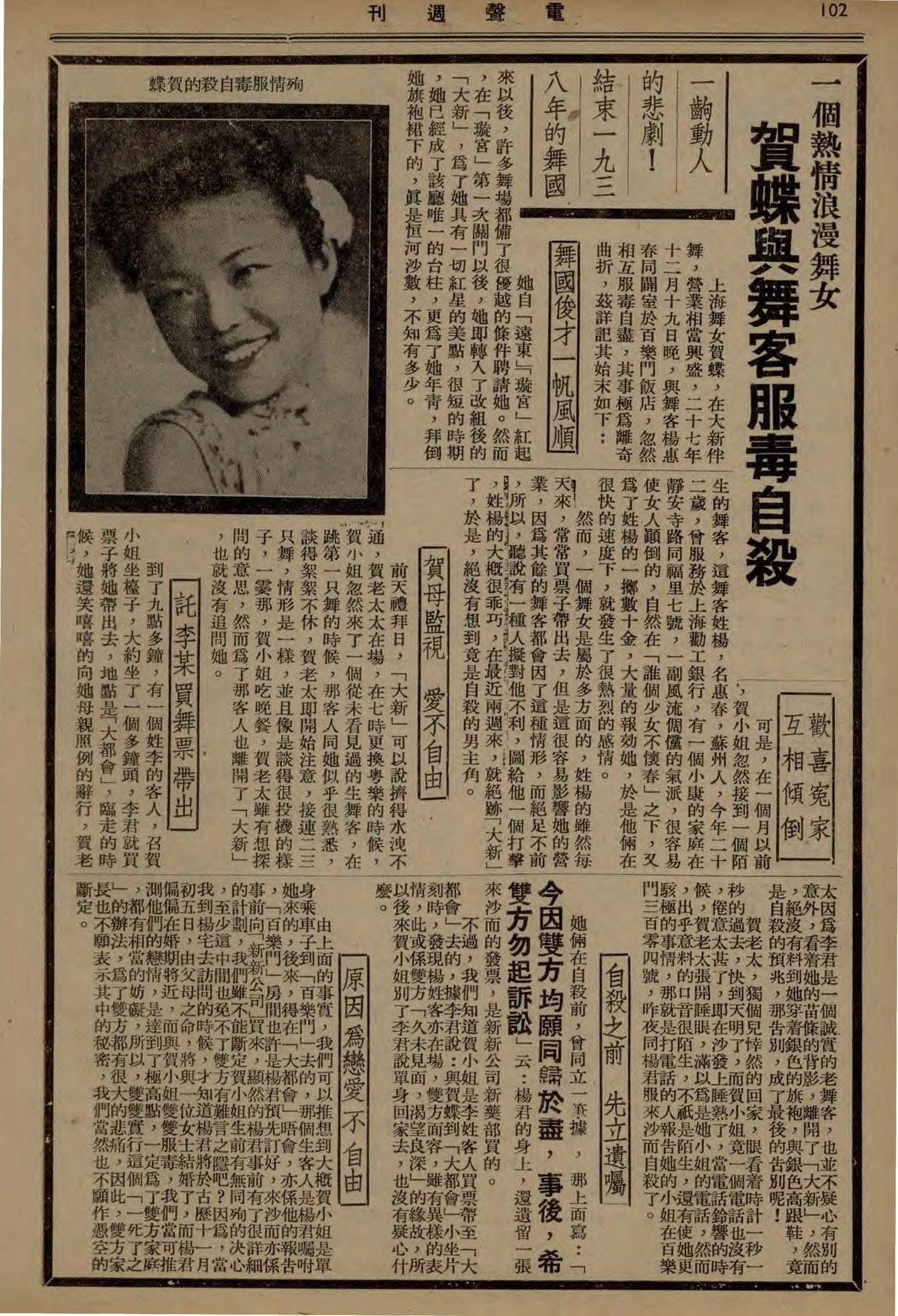

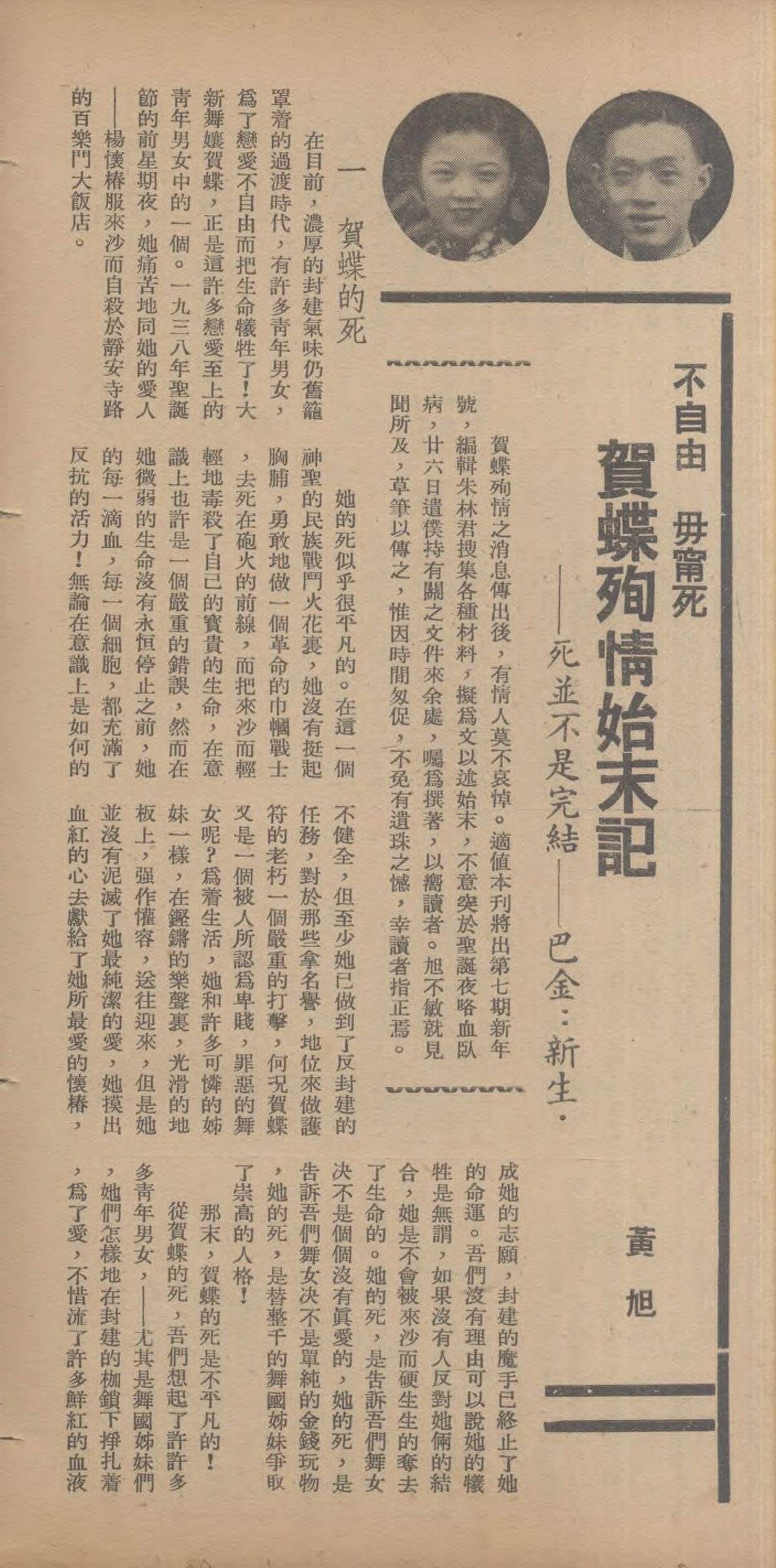

For example, the story of the dancer He Die (贺蝶) and local scion Yang Huaichun could have been a Republican Romeo and Juliet.

Zhou Licheng: Coming from humble origins, He Die entered this “lowly” profession in order to support her family. At the time, dancers were viewed with contempt, but through her quest for survival, she eventually emerged a star.

Just as she was trying to settle down, Yang Huaichun appeared on her horizon.

Yang Huaichun was a Suzhou native, fair-skinned, elegant, and charming. His father was of some local renown. Although the family wasn’t extremely wealthy, he was the only son among three branches of the lineage, so both parents naturally doted on him. At the time, he worked at the China Quangong Bank in Shanghai and relied on his family’s support. When he met He Die in a dance hall, it was love at first sight. Their affections quickly reached a boiling point.

Zhou Licheng: Yang Huaichun didn’t miss a single performance by He Die. At the time, He Die was a mainstay of the dance hall, a real money tree. Patrons would line up to dance with her. But once Yang Huaichun came on the scene, she no longer had time for the others—it actually affected the business.

Unexpectedly, He Die’s mother learned of their love affair. She felt her daughter wouldn’t make it as a social climber. In her view, a basic requirement for marriage was being well-matched in social status. Since the other party was a son of privilege, her daughter was bound to be unhappy.

So He Die’s mother became her shadow, accompanying her to and from the dance hall to close off any opportunity for Yang Huaichun to get close to her. The couple wasn’t daunted, but down below tragedy was brewing.

On December 18, 1938, wearing a silver-white qipao and a pair of silver-white heels, He Die left the house calmly.

Zhou Licheng: After getting to the dance hall, a patron invited her out. He Die’s mother thought the man reliable, so she didn’t follow. The two of them went to a place of entertainment and stayed out until midnight.

But the man had actually been hired by Yang Huaichun to draw her out. Once the lovers were reunited, they headed to the Paramount Hotel. Yan Huaichun said, “My parents know about us. They’re firmly opposed, and are forcing me to get married in a few days.”

Though he may have been a man, Yang Huaichun didn’t have much of a spine. He didn’t try to assert himself. Having prepared some Lysol, he said, “If I can’t have freedom, I’d rather have death.”

The two of them proceeded to sing, bathe, and carouse in a final bout of revelry. As the sun rose outside the window, they drank the poison together.

When the hotel staff found their bodies, there was a suicide note, two diamond rings, two empty Lysol bottles, and a pile of bank notes on the table next to them, amounting to 213 yuan. The suicide note explained that this was settlement money for the He family. It continued, “As both parties were willing to die together, I hope neither party will sue.”

Many papers reported heavily on the joint suicide of He Die and Yang Huaichun, and a public controversy ensued.

Zhou Licheng: In 1938, the nation was deeply embattled. Some voices argued that, rather than dying indulgently for love, young people ought to take up arms against the Japanese. Other voices said that dancers and actors were “heartless”—wherever there’s a stage, they’ll make a farce. But He Die’s death proved them wrong. Dancers do indeed love, and they can have just as much courage in the name of love as anyone else.

-4-

The consort’s revolution

The May Fourth Movement shook the foundations of traditional matrimony. Young people, led by intellectuals, advocated for a freer and more equal system. After generations of enforced passivity, many women were roused to action.

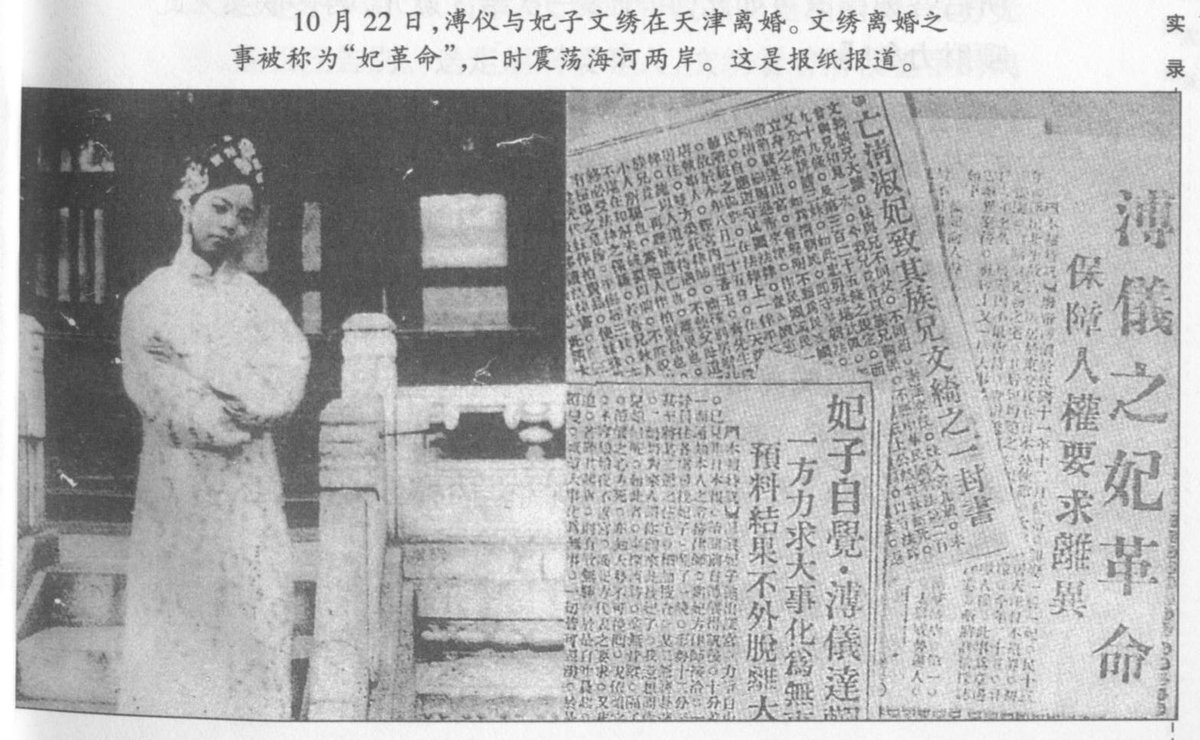

The most famous example may be the divorce of Consort Wenxiu (文秀) from the last emperor, Puyi (溥仪)—an event that was exhaustively documented in contemporary media.

Zhou Licheng: Why would Wenxiu so brazenly propose divorce?

In my analysis, there are a few reasons. First, under the new Civil Code of 1930, monogamy became the official law of the land. At the time, Puyi’s empress consort was Wanrong (婉容), while Wenxiu was considered secondary—equivalent to the concubines prohibited by the new laws. She refused to recognize herself as such.

At the same time, Puyi was indeed partial: Wanrong had a domineering disposition, believing herself to be the rightful empress and squeezing Wenxiu out at every opportunity.

Besides getting less of a monthly allowance than Wanrong, Wenxiu and her servants also lived in one small room while Puyi and Wanrong slept in a room on the floor above. She suffered from insomnia as a result, often reading in silence until dawn.

Wenxiu had a younger sister, Wenshan. A progressive woman, Wenshan encouraged her sister to change her life.

So one day, when Puyi was in a good mood, Wenxiu fled the imperial palace, telling her servants: “You can go back, I am divorcing Puyi.”

It was quite inconceivable for a concubine to divorce the emperor. Each party retained a lawyer. Wenxiu proposed several alimony conditions; if Puyi agreed, she wouldn’t take him to court. Puyi’s only condition was that there be no lawsuit.

What they didn’t anticipate was that, on the third day of negotiations, Business News suddenly published a letter from Wenxiu’s older cousin, forbidding her divorce from Puyi. The letter included this sentence: “When a ruler commands his subject to die, the subject has no choice but to die; the righteousness of ruler and subject, the difference between superior and inferior, means we must accept our fates and abide for the duration of our lives!”

With the publication of that letter, the last emperor’s divorce proceedings came into full view of the public.

On September 2, Wenxiu returned fire in the New Tianjin Post: Not only did she have no previous contact with her cousin, but he was also disregarding the laws of the Republic and denying her equal rights. She ended the letter with this barb: “I invite my cousin to read more law books and practice the art of discretion, so as to not violate the laws of the Republic of China.”

After a month of negotiation, Wenxiu and Puyi agreed to an alimony totaling 55,000 yuan, and requested that the formalities be conducted in the shortest time possible.

The day after the proceedings were finalized, Puyi tried to save face. He published this imperial edict as a masthead ad in Beijing, Tianjin, and Shanghai newspapers: “The imperial concubine has abandoned the garden, violating ancestral teachings; she is stripped of her title, reduced to a commoner, by order of the Emperor himself.”

By then, the Qing dynasty had already been over for 20 years.

Zhou Licheng: After the divorce, Wenxiu’s life was not all smooth sailing. The 55,000 yuan went into lawyer fees and housing, leaving her very little in the end.

Later, Wenxiu worked as a teacher, but people gossiped about her and mistreated her once they learned of her identity. She then married a military officer before dying at the young age of 44.

I combed through the papers from the years after her divorce, 1932 and 1933, to see what impacts the “consort’s revolution” had on society.

I found that there was a sharp increase in the number of women filing divorce or taking out lawsuits, particularly in northern China. Women cited three primary reasons for divorce: Domestic violence, abandonment, and failure of their husbands to provide for them economically.

The February 1933 issues of Yishi Post include six consecutive reports of women filing for divorce. These reports reveal a common fate for women on the lower rungs of society.

For example, a Beiping woman surnamed Li (nee Wang), confided to a court mediator: “I have been married to Li Zhongyu for six or seven years. He doesn’t support me, has a heroin addiction, and has forced me into prostitution in a Nancheng brothel. I can’t bear to stay with him anymore, and ask for a divorce.”

The mediator asked, “Who will the children go to?” Mrs. Li said, I don’t want them. So the children’s custody went to the father, and the divorce was successful.

Through numerous such reports, it becomes apparent that the courts had a set of principles for mediating these proceedings, rather than uniformly pushing for reconciliation or divorce.

-5-

Remarrying as a widow

Republic-era pictorials actually document many unorthodox and experimental weddings.

There were already aerial weddings and water weddings, as well as group ceremonies. There were weddings that were as simple as a meal between friends, and there were political alliances that took shape as weddings of the century.

Even as ceremonies shifted in form, attitudes toward marriage remained relatively conservative.

Zhou Licheng: 1935 was a watershed year in the history of marriage in China, and Wei Wenxiu’s remarriage was one the most important events of that year.

Originally from a red-light district in Hubei, Wei Wenxiu met Li Yuanhong (黎元洪)—the Beiyang government’s first president—at a dinner party. He made her his concubine, and changed her name to Li Benwei.

At the time, it was very common for government officials to take concubines from the red-light district. Far from threatening their reputation, this practice was seen as fashionable.

Li Benwei had a knack for the nuances of communication, and was deeply trusted by Li Yuanhong. She once went to the front lines to visit soldiers on his behalf, and even took charge of his official seal. The papers of the day were united in their praise for her.

But the good times didn’t last. A few years later, Li Yuanhong passed away. Thanks to his favor in the will, Li Benwei didn’t lack for food or clothing. But in 1934, after a conflict with the Li children made its way into the courtroom, she cut ties with the family.

She changed her name back to Wei Wenxiu and started her own business. She also became romantically involved with a silk merchant more than ten years her junior, Wang Kuixuan. In order to marry him, Wei Wenxiu turned over all the property in her name and took only a small sum in alimony. The pair held their wedding in Qingdao in order to evade her family’s opposition.

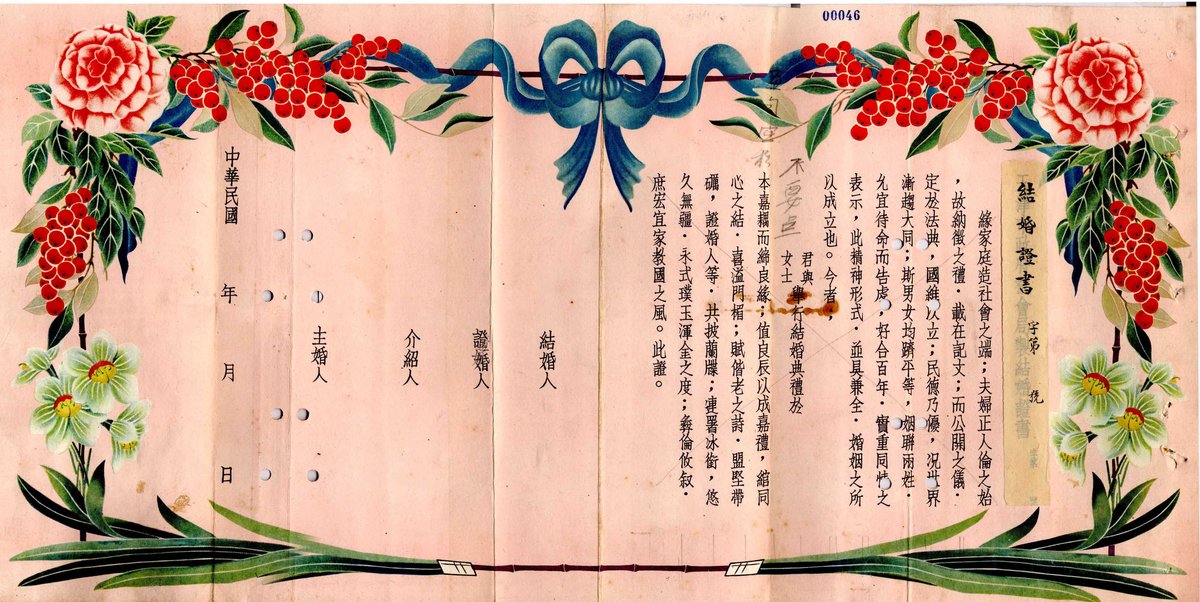

In the early days of the Republic, there were in fact no official marriage certificates. Common people who could afford it might post a marriage announcement in the paper, or arrange for a witness to their ceremony.

So Wei Wenxiu announced in the papers that she would be marrying the merchant Wang Kuixuan. Unexpectedly, this ignited a major controversy.

Zhou Licheng: Li Yuanhong was from Hubei, so it was Hubei’s hometown association in Beijing that first published an article lambasting Wei Wenxiu: By tarnishing her role as the President’s widow, she was tarnishing the whole country.

Qingdao’s mayor, Shen Honglie, had Wang Kuixuan arrested and expelled Wei Wenxiu. He posted a notice in the paper compelling Wang Kuixuan to divorce her.

Wei Wenxiu had already arrived in Hangzhou by then. Upon hearing this news, her hopes were crushed. She fled into monastic life, becoming a Buddhist nun.

But just one month later, on February 9, 1935, the 66-year-old educational philanthropist Xiong Xiling married Mao Yanwen, a woman 20 years his junior. The public reaction was one of envy and admiration, with more than a few people writing poems celebrating the union.

It is said that in order to satisfy the wishes of his new wife, Xiong Xiling shaved off the long beard he had kept for over 10 years. The press made a big deal of this, embellishing the account and celebrating it as a symbol of marital harmony. As the media spread news of the wedding around the country, it became a surprising exemplar.

Another two May-December weddings were held the next month, in each case between an older man and younger woman. These caused an even greater sensation.

This drew the ire of Wei Wenxiu, who did not understand why she, conversely, had to endure separation from her lover. Was it only because she was a woman and a widow?

Zhou Licheng: Wei Wenxiu left the monastery with a conviction and went to the Women’s Federation in Shanghai. Wielding the force of the law, she published an open letter in Shen Bao:

“Humanity’s love is ordained by Heaven, and it knows no bounds. It is not forbidden for a widow to remarry; to suffer alone is the choice of a foolish woman.”

Wei Wenxiu’s remarriage was a topic of debate in all corners of society. But in the end, the conservative opinion prevailed: “Starving to death is no big deal, but losing one’s virtue is no small matter.”

After Wei Wenxiu and her new husband divorced, she was never able to return to her social life. She wanted to return to Beijing to stay with relatives, but they refused further contact with her.

Once again, she was all alone in the world.

If we look at things from her perspective, she had done all she could do, yet it all came to nothing. The last time she appears in the public record is when she was arrested in a casino.

Having been reduced to a commoner, Wei Wenxiu no longer received the papers’ attention. Her ultimate fate is unknown.

-6-

Pictorials from the front lines

The latter half of the Republic was a time of social unrest, with troubles brewing within and without. But the upper crust persisted in its old life of luxury, holding grand weddings and celebrations. Meanwhile, the middle and lower classes were caught in the crosshairs of national conflict, worrying about their next meal.

Zhou Licheng: In the same issue of a pictorial, you might see hair ornaments, Republican fashions, and Western styles on one page; on the next, there might be images of the shelled-out homes of displaced civilians.

On one hand, you see the wedding of the covergirl Hu Die to Pan Yousheng, her in a spotless white gown and him standing tall in a Western suit. Meanwhile, the common people were skipping the betrothal six rites, letting matchmakers marry their daughters off to unknown men to protect them from humiliation at the hands of the invaders.

The pictorials of the time reflect this surreal collision of time and space.

After the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, pictorials began to decline in both number and variety.

The war gave rise to different factions and disruptions to transportation, severely impacting the distribution of pictorials. The industry contracted; many of the papers that hosted the angry rebukes of yesteryear folded. Old issues circulated among the public, awaiting rediscovery by people such as Zhou Licheng.

Mr. Zhou’s book has currency even in today’s world. It doesn’t feel like a story from the past; instead, the circumstances and choices of the people represented seem to be in conversation with current events.

When people look at today’s “pictorials” in 100 years from now, who knows what they will make of us?

Images courtesy of Zhou Licheng

___

This story is published as part of TWOC’s collaboration with Story FM, a renowned storytelling podcast in China. It has been translated from Chinese by TWOC and edited for clarity. The original can be listened to on Story FM’s channel on Himalaya and Apple Podcasts (in Chinese only).