Rainbow Chan remembers the beauty and cheese of the golden age of Canto and Mandopop, acknowledging its mark on her identity while also stamping it with her own

Paying homage is a tricky business. There’s always the danger of entering imitation territory and one’s work becoming derivative or less original as a result.

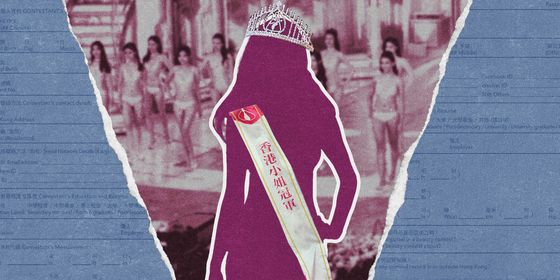

Asian Australian musician Rainbow Chan (雋然), usually found recording club music and experimental electronic tracks, skillfully traverses this fine line between imitation and art with her latest album Stanley (released in November 2021), producing a breathtakingly transcendental record wrapping English lyrics around strains that pay fond homage to the golden era of Mandopop and Cantopop that existed in the 1980s and 90s.

It is more than just a trip down memory lane, but a personal exploration. Letting flashes of her own experiences weave through the album, sometimes subtly and at other times starkly, Chan uses the devices of the Mandopop and Cantopop genres to tell her own story; furthering her own understanding of her identity and her relationship with a Hong Kong from her childhood.

Born in Hong Kong but raised in Sydney, Rainbow’s dual identity has been key to her works since her debut in 2012. A critically-acclaimed multi-hyphenate musician, producer, DJ, and visual artist, Chan has built a small but steady niche following within the Asian diaspora for the unique ways she incorporates her heritage into her electronic sound. From exploring her Weitou (indigenous inhabitants of Hong Kong since the Song dynasty) heritage through wider discussions on migration and belonging in previous 2019 album Pillar, to drawing on her childhood experiences of Hong Kong in Stanley (named, Chan told NME, after a kitsch Hong Kong suburb Chan’s parents went to buy denim jeans for their fashion boutique), Chan continues to surprise at every turn with her inventive and emotional works.

In an interview with Electric Soul in November 2021, Chan described Stanley as a collection of colorful, gaudy trinkets whose value is purely sentimental, ornamental, and eventually obsolete. Yet there is value to the nostalgia emanating from the 8-track album, especially for the tribute it pays to pop music gone by.

Inspired by well-known singers of the 80s and 90s (Chan called them “Divas” in an interview with Asian Pop Weekly), such as Teresa Teng, Faye Wong, and Anita Mui, Chan uses a multitude of devices—chord progressions, lyrics, vocal production, instrumentation—to create a skeleton unmistakably based on retro Mandopop and Cantopop ballads: From the mysteriously theatrical “Heavy (沈重),” a rich tapestry of retro synth laden with strings which reminds of the famous wistful strains of “Yumeji’s Theme” from the Palme d’Or-nominated Hong Kong romance In The Mood For Love (2000), to the over-the-top playfulness of the Faye Wong-esque “Idols (偶像).”

Chan’s unique and modern take on a classic sound is born out of the temporal yet fascinating history of Cantopop in Hong Kong, in particular the 1980s and 1990s that were such key decades for the genre.

While the main difference between Cantopop and Mandopop lies in the language it is sung in, the genres have been inextricably linked in the context of Hong Kong; they began to show clearer distinction in the 1970s with early Cantopop drawing from Cantonese Opera and the influence of film and TV.

Following in the footsteps of the unexpected success in the 1970s of local Cantonese content at box offices and on television, Cantopop theme songs for TV shows on TVB (a prominent Hong Kong broadcasting company) such as A Love Tale Between Tears and Smiles began to change local and regional perceptions of the style being vulgar and low-brow.

The proliferation of ground-breaking films such as The House of 72 Tenants (1973) and Games Gamblers Play (1974), and the debut of artists such as Anita Mui, Leslie Cheung, and Sam Hui allowed Cantopop to reach new heights in the 80s and 90s before its untimely decline, brought on by waning public interest and the increasing clout of Mandopop in the region.

For Chan, it was the “Divas” of Cantopop and Mandopop that inspired her contemporary interpretations heard on Stanley, and for good reason too. Despite debuting in an era dominated by male stars (Sam Hui, Leslie Cheung, Alan Tam), artists like Anita Mui with her non gender-conforming and chameleon-like sound, and Teresa Teng (a legendary figure influential in popularizing the genre from the 1970s until her tragic death of an asthma attack in 1995) with her enchanting, honeyed vocals came to define this golden era.

It is through their legacy, alongside other important singers like Faye Wong, Sammi Cheng, and Joey Yung, that this golden era of Cantopop has continued to be romanticized and memorialized throughout pop culture until this day. From the 2021 film Anita depicting the life of Anita Mui, to the countless contemporary reimaginations of Mandopop and Cantopop classics by the likes of Khalil Fong, Joanna Wang, and 9m88; two decades on the genre still evokes an irresistible nostalgia in listeners around the world.

This nostalgia is what Chan seeks to unpack in Stanley. Inspired by the physical restrictions of the pandemic in Sydney and a homesickness for Hong Kong, Chan’s love of these Mandopop and Cantopop stars drove her to take on the challenge of incorporating their essence into her music. Identifying characteristics that defined the genre—romantic natural imagery in the lyrics, particular chord progressions, and even certain vocal techniques used by the divas—are all here.

“With the Divas, I think when they sing, they have a slightly more pure tone and are a little bit more nasal…[so the song] has a slightly brighter sound,” Chan explained in an interview with Asian Pop Weekly in February, describing the “Cantopop Diva” sound she tried to recreate on Stanley. “There were certain demos where I really would sing just like Teresa Teng and then dial it back later on just to make it sound like myself.”

Unlike her previous club and electronic records, where Chan’s vocals tend towards a more breathy sound, dancing lightly on top of each note, on Stanley she adopts a lazier and pronounced melisma, with notes held longer and merged together (for example in “Ylang Ylang”) to create the heady sense of longing which defines many a Cantopop and Mandopop ballad, such as Anita Mui’s classic “Flower of the Woman” (1997).

On “Ylang Ylang,” the use of Tango rhythms populated by synths and backed by extravagant strings absorbs the listener into an atmosphere of dramatic mystery not unlike those Teresa Teng was so skilled at creating. It’s an exhilarating listening experience that feels like a dance between the past and the present; where Rainbow’s twinkling beats combined with old-age rhythms create a delicious tension that keeps you coming back for more.

Another stand out is Chan’s intriguing translation of the poeticism of Mandarin and Cantonese lyrics into English. While translation often prioritizes conveying emotion over choice of words in order to fit meaning into different cultures, Chan’s translations instead intend to capture words and articulate as is, whether or not they entirely fit into a Western context. Fully capturing the essence of those woeful “love me/love me not” ballads on tracks such as “Love Note (情書),” Chan’s use of extended, flowery-to-the-point-of-sickeningly-sweet metaphors are genius and endlessly fun to interpret:

Did we fall from the same branch?

Are we two halves of a peach?

With our stoney hearts and tender flesh

Longing to return to each other

Lyrics from Chan’s “Love Note (情書)”

我有花一朵 种在我心中 (I have a flower seeded in my heart)

含苞待放意幽幽 (A bud waiting to be relieved)

朝朝与暮暮 我切切地等候 (Day and night I wait)

有心的人来入梦 (For someone with a heart to enter my dreams)

Lyrics from , Anita Mui’s “Flower of the Woman (女人花)”

While in the past two decades since Cantopop and Mandopop enjoyed a golden age the genre has been reduced to a mix of, as The Straits Times put it in 2002, “big ballads and cheesy dance tunes,” Stanley is a perfect example of how the genre’s unmistakable characteristics continue to be memorialized but can also be repurposed in innovative ways by artists today. More than that, Chan’s work is a weighty argument for the critical necessity of preserving and appreciating this moment in Chinese musical history, given its lasting legacy.

Written by Jocelle Koh

This story is published as part of TWOC’s collaboration with Asian Pop Weekly.