Delingha in Qinghai was made famous by revered poet Haizi, now the city is trying to use that fame to boost tourism

“This is a desolate city in the rain, except to the people who live there and those who pass by,” Zha Haisheng, commonly known as Haizi (海子), wrote one night in 1988 about the remote city of Delingha in China’s far-western Qinghai province.

Eight months later, at the age of 25, the poet lay on railway tracks at Shanhai Pass in Hebei province, holding a Bible in his hands as he said farewell to this world.

After his death, Haizi became one of China’s most revered modern poets. During his short seven-year career, Haizi wrote over 200 short lyrical poems and 10 long poems. He posthumously won the Chinese Literature Prize for Poetry in 2001, and is seen as a representative of the “Third Generation Poets,” a group that emerged in the 1980s whose poetry was influenced by postmodernism and characterized by a focus on everyday local life, irrationality, and anti-heroism.

Haizi often wrote about rural life and nature, frequently referencing crops, villages, the moon, and the sky. His work had a huge influence on Chinese poetry in the 90s, as he became a household name among literary youths. Some of his most famous poems, such as “September” and “Facing the Sea, with Spring Blossoms,” were made into songs by the likes of pop singers Kenny (阿鲁阿卓) and Chris Lee (李宇春).

But Haizi’s legacy also included turning the city of Delinghua—a place Haizi described as “desolate”—into a pilgrimage site for China’s literary youth through his poem, “Sister, Tonight I’m in Delingha.”

Fans of Haizi are drawn to his work in part because of the mystery of his short life, about which little is known. Born in 1964 in rural Anhui province, Haizi studied law at Peking University and began writing poetry in 1982.

There are two legends about the inspiration behind his Delingha poem. One story is that the poet traveled to western China in pursuit of a female writer 20 years his senior, who had refused his advances, and wrote the poem for her. The other version is that Haizi traveled to Tibet for inspiration and stayed at Delingha one rainy night during his trip, penning the poem while grieving for a lost romance.

Delingha, which was upgraded from a county into a city in 1988, the same year Haizi visited, has a total population of just 78,184, but now attracts pilgrims who come from all over China to pay tribute to Haizi and experience the same emotions the poet described so eloquently.

Today, Delingha is still remote. The city sits at around 3,000 meters in altitude, with Qinghai Lake to the east and the Tibetan Plateau to the west, and is surrounded by the Kunlun and Qilian Mountains. Delingha is the capital of the vast and beautiful Haixi Mongol and Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture in the Qaidam Basin. The city’s Chinese name is transliterated from Mongolian, meaning “Golden World.”

According to legend, Güshi Khan, the leader of the Mongol Khoshut tribes and a descendant of Genghis Khan, led his people south to the Qaidam Basin during the 17th century. He set up his own kingdom there, and gifted Delingha and land around it to another tribal leader. That leader, whose name is not recorded, was spellbound by the sun shining on the vast prairies at Delingha, complimenting the place as a “golden world.”

Though Haizi described a deserted, seemingly forgotten outpost in the arid Qinghai desert when he visited, Delingha was once an important resting point on the ancient “Southern Silk Road” (which dates back to 1,000 BCE). Centuries later, it would be an important grazing area for livestock for ethnic Mongolians. Delingha emerged as a rare oasis in the Qinghai desert because the Bayin River—“Fertile River” in Mongolian—flows through the city and nurtures crops in the area.

Today, it’s also an important transportation hub, with both the Qinghai-Tibetan Railway and National Highway 315 passing through. It is a railway junction that connects to Tibet in the south (with Lhasa a 17-hour train ride away), Gansu in the north (six hours by train to the provincial capital of Lanzhou), Xinjiang in the west, and Xining, the provincial capital of Qinghai, four hours by train to the east.

At high altitude, highland barley, wolfberries, and quinoa are the main crops in Delingha, while yak and lamb are staple meats. Locals enjoy roasted yak or lamb plainly seasoned with salt, combined with roasted highland barley known as tsampa.

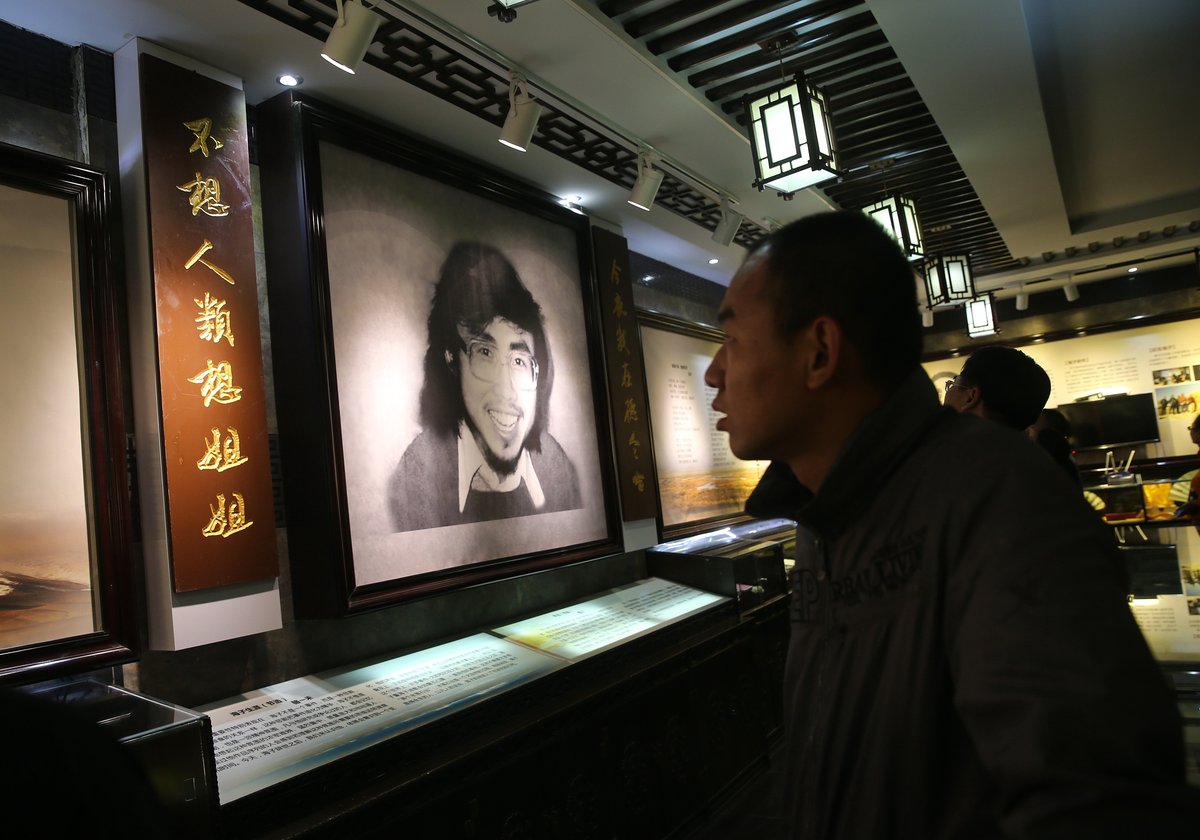

Delingha has latched onto its association with Haizi and attempted to attract tourists eager to engage with the legendary poet’s legacy. A Ferris wheel, fountains, and the Haizi Exhibition Hall suggest the city is no longer the abandoned outpost that Haizi had described.

In 2012, the same year the city opened the Haizi Exhibition Hall, the Haizi Poetry Festival was held for the first time and has been held every two years since. Haizi’s influence is everywhere in the city. Strolling along the river, there are Haizi-themed pubs, and restaurants named after the writer.

How exactly these places relate to the poet is unclear, but every year, artsy tourists continue to visit. Another attraction is a forest of stone tablets, each inscribed with Haizi’s poems.

However, these attempts to develop the city’s tourism industry by associating with Haizi’s legacy means the environment in the poet’s verses is largely lost to history—more romantic in the reader’s mind than in real life. People who visit with the expectation of seeing a city in solitude will likely leave with disappointment. While Haizi described Delingha as “the last prairie” and talked of the emptiness of the Gobi Desert, the city has been developing its energy and tourism industries based on its abundance of minerals and proximity to other famous travel spots such as Qinghai Lake.

The buildings are growing taller, and the night view with neon flashing can also be seen on the both sides of the Bayin River. Yet, if you happen to stay at the hotels in Delingha for a night, you might still see shampoo bottles adorned with images of popular celebrities from the 90s, use an electric blanket for heating, or have nothing but a few flavors of instant noodles available to eat: all things reminding you that this county-level city is still long way from China’s urbanized east—physically, economically, and perhaps emotionally.

Rather than Delingha the city, visitors may find the best place to feel close to Haizi’s poetic descriptions is outside the urban area, deeper in the desert, at night when the high sky is full of stars. Then one can truly feel the Delingha in Haizi’s words:

Sister, Tonight I’m in Delingha

姐姐,今夜我在德令哈

Sister, tonight I'm in Delingha, as the dark night draws its curtain.

Sister, tonight I have only the Gobi Desert.

At the end of the prairies, my hands are empty,

But when I feel sad, they can't even hold a drop of tear.

Sister, tonight I'm in Delingha,

This is a desolate city in the rain,

Except to the people who live there and those who pass by.

Tonight, here in Delingha,

This is the only, and the last, expression of the mood,

This is the only, and the last, prairie.

I’ll return the stone to the stones,

Let victory be victorious,

Tonight, the barley that someone grows belongs to only itself

While everything is growing.

Tonight, I only have the beautiful and empty Gobi Desert.

Sister, tonight I don’t care about humanity, I just miss you.

Translation taken from The CD Box, translator unknown. It has been lightly edited for clarity.