Chinese science fiction is finally being translated into English beyond Liu Cixin’s famous Three-Body Problem

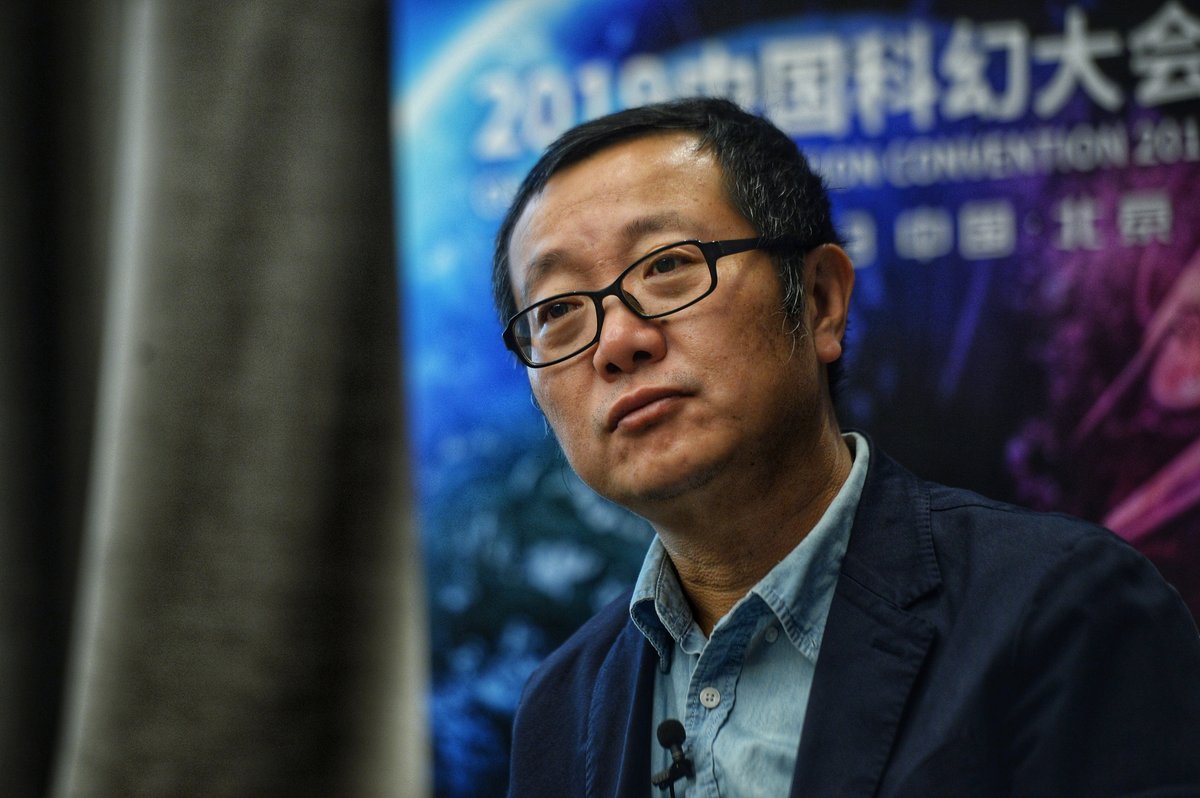

When Liu Cixin’s The Three-Body Problem emerged in 2015 as the first novel out of Asia to win a Hugo Award, the highest honor in science fiction literature, the search began to find China’s other gems.

It’s not been a simple task, but recent translation efforts are now revealing Chinese sci-fi to English-speaking audiences. In short story anthologies—most recently Xueting Christine Ni’s Sinopticon last month—and digital magazines (like the non-paywalled Clarkesworld), international readers are gaining greater access to China’s sci-fi canon at long last.

Sci-fi in China goes back to the 1900s, when Lu Xun (鲁迅) and other intellectuals translated Jules Verne as a way to educate the general population about science and build a modern China. “Leading the Chinese people forward begins with science fiction!” was the slogan Lu Xun printed in the preface of From the Earth to the Moon (《从星球到月球》).

Authors stuck to that motto for the next half-century, through the era of ambition and aspiration between the foundation of the PRC in 1949 to the Reform and Opening Up of the 1980s, even if their quality fell short of their ambition, “most works [of the time] were technological conjecture at their core, with simple characters, nearly no humanistic themes, and a simplistic writing style that was crude even for those times,” writes Liu Cixin in a 2017 essay “A Century of Western Winds: A Brief Discussion of the Influence of Foreign Science Fiction on Chinese Science Fiction Literature,” translated by Jesse Field.

The genre’s international flavor put it at risk when politics turned against foreign influence: Writers were forced underground during the Cultural Revolution, and sci-fi magazines closed during leftist backlashes to social reform in 1983 – 1984 and 1986 – 1987.

But by the 1990s, as social reform continued and a market for Western sci-fi translations swelled and sped up, Chinese readers could finally access all the science fiction the world had to offer. At their fingertips were more than just “Golden Age” giants like Isaac Asimov or Arthur C. Clarke, but “New Wave writers”—who preferred literary beauty over plausibility—like Philip K. Dick and Ursula Le Guin, and cyberpunk authors like William Gibson.

These authors all fed the imaginations of the authors that influential sci-fi writer and critic Regina Kanyu Wang identifies as the “Big Four” of Chinese science fiction (Liu Cixin, Han Song, He Xi, and Wang Jinkang), whose works remain mostly untranslated, but have been widely circulated in China through magazines like Science Fiction World and online forums. Their work in turn spurred a newer generation of Chinese sci-fi authors, who are just now getting the recognition and the translations they deserve.

Liu is the most celebrated of the Big Four with nine Galaxy Awards (China’s highest sci-fi accolade), his Hugo Award, and a 2019 adaptation of his novella The Wandering Earth by China Film Group. His style also typifies that of the group. His breakthrough trilogy (which began with The Three-Body Problem) was the first to demonstrate those authors’ “world-creating consciousness,” as he calls it in his 2017 essay, with thorough exploration of the human impact of new technologies in stories that span multiple centuries and star-systems.

He’s by far the most translated Chinese sci-fi author, usually at the hands of polymath Ken Liu (no relation). Besides his three novels, English readers can find Liu’s short stories online in Clarkesworld and in several anthologies. A quintessential example is “The Circle,” in Ken Liu’s short story collection Invisible Planets (2016), set in the Warring States era of ancient China as the ruler of the Qin kingdom considers creating a “computing army,” the soldiers at his command forming the circuits and gates of modern computers.

The other Big Four writers don’t enjoy nearly the same rate of translation, despite each winning at least six Galaxy Awards (and 10 for Wang Jinkang). So far, only three of Wang’s shorts can be found in translation: two in Paper Republic (translated by Carlos Rojas) and his 1995 story “The Return of Adam” translated by Xueting Christine Ni in Sinopticon. That tale sees humanity explore the stars and connect our brains with AI, featuring a protagonist who slips from determined optimism to a somewhat maudlin determinism, where individual free will counts for nothing in the face of exterior forces beyond our control.

He Xi remains completely untranslated, unfortunately, but Han Song’s “Tombs of the Universe” is also available in Sinopticon. In two loosely-connected parts, this short from 1991 fixates on death monuments in humanity’s interstellar future. The tone shifts frequently; sometimes hard-boiled, sometimes romantic. But unlike the science-centered stories of Liu, Han spends more focus on the emotional impact of this future.

This attention to the individual and their perspective is characteristic of a newer set of writers that Liu Cixin calls “a Chinese echo of New Wave science fiction.” In “A Century of Western Winds,” he explains their work is about “reflecting the existence of the universe through individual sensation and sentiment.”

Perhaps one of best of this set of writers is Xia Jia, a two-time Galaxy Award winner with expertise in atmospheric physics, film history, and comparative literature. Ken Liu has translated many of her shorts, in two anthologies and 2021’s A Summer Beyond Your Reach, a book devoted entirely to her work. Readers can also find her in translation on Clarkesworld, including “If on a Winter’s Night a Traveler” from 2015. This little mystery follows a librarian’s daughter who discovers a powerful poet, as well a group of readers dedicated to eliminating her work. There’s no distinct element of science here, but it provides a charming introduction to the voice and concerns of this popular author.

One more author worth attention is Baoshu, winner of three Galaxy Awards and the author of Redemption of Time, a novel set in the world of Three-Body that was so good Liu Cixin and his publisher authorized it as a sequel. It’s available in English, thanks to Ken Liu, and Baoshu’s shorts can be found in both Clarkesworld and Liu’s short story collection Broken Stars (2019). “What Has Passed Shall in Kinder Light Appear” is included there, a brainy and intriguing story picturing Chinese history in reverse, going from rich to poor and capitalist to socialist as time is inverted and the trappings of China’s hyper-modern future disappear.

For the curious English reader, there is a new bounty of award-winning authors to discover. With so many translations published recently, and surely more in store, the full spectrum China’s deep and diverse science fiction scene is finally coming into focus.