“I’m no chem whiz, I just needed to save my son”: Unable to find medicine for his son’s Menkes syndrome, a father decides to make his own

If your child was diagnosed with a rare disease, and there was no readily available medicine to treat it, what would you do?

How far would you go to save your child?

Xu Wei, the protagonist of this story, is facing precisely these choices.

His son, Haoyang, has Menkes syndrome, a rare genetic copper-deficiency disorder that affects just one in 50,000 to 250,000 people. In order to prolong his son’s life, Xu started researching the disease from the ground up. He studied medicine and chemistry, and even, out of desperation, began producing his own drugs.

Here, Xu describes the series of “impossible tasks” he performed in order to save his child’s life.

Hello everyone, I’m Haoyang’s dad. I have a high school education, and previously ran a small online shop on Taobao. Due to a mutation on the ATP7A gene, my son suffers from a rare disease called Menkes syndrome. For him, I synthesized chemical compounds and researched gene therapy, looking for ways to keep him alive.

-1-

A mystifying illness

Haoyang was born in 2019. When he was around six months old, we found that he couldn’t roll over and lift his head like other infants his age, so we took him to the hospital for a check-up. We wanted to see whether he had any developmental delays. We did the standard tests, like bone density, reflexes, even an eye exam, none of which showed any abnormalities. We just couldn’t figure out what was going on. The doctor recommended that we do a comprehensive genome sequencing to see if there were any issues with his genes.

At the time we didn’t think there could be any issue with his genetics, because no one in our family has had any health issues, including his grandparents. We weren’t convinced, but there was nothing else to be done. Haoyang continued to have developmental delays and couldn’t move like other children his age, so we had no choice but to get a genetic analysis done.

-2-

A diagnosis, but no medicine

Due to the pandemic, there was a roughly three-month wait to get the results. During those three months, Xu was suspended in anxiety.

I remember I was driving when I got the call from the doctor: “We’ve got the genetic analysis here”—so I asked him what the results were. He told me to prepare myself, that it was best that I look up Menkes syndrome. He told me how to spell it, said that I should go learn about it for myself first.

My first reaction was shock. I was in disbelief. But I went and looked up Menkes syndrome. There was very little information about it on Baidu. I saw that there was no medication available to treat the disease. I was on the verge of collapse. I wanted to get to the hospital as quickly as possible to hear the doctor’s explanation—but the doctor told me there was no medicine for treating Menkes on the Chinese mainland, so we could only wait until my son had symptoms to come back to the hospital to get treated.

The doctor told Xu that Haoyang was the first Menkes patient at that hospital, as well as the first recorded case in Yunnan province. Even the doctor had needed to consult additional resources in order to properly explain Menkes syndrome to Xu.

Xu still didn’t believe that such a rare calamity would fall on him. To get a second opinion, he found a doctor who had treated a child with Menkes before, and flew from Kunming to Beijing for an in-person consultation. But whether it was genetic analysis, or biomarkers, or physical symptoms, everything indicated that Haoyang had the rare disease.

Menkes is an inherited copper-deficiency disorder. Due to a mutation on the X chromosome, Menkes patients can’t absorb copper ions. The illness results in protracted suffering, slowing down a child’s growth and development. When other infants his age could roll over and crawl, Haoyang would often just lie there. Copper deficiency also causes neurodegeneration similar to what’s seen with Alzheimer’s disease: At first, patients can move and smile, but toward the end, they lose all motor control—even swallowing becomes difficult.

The condition can be treated with external copper ion supplements. The most common, copper histidine, is directly injected into the body. But copper histidine is still unavailable on the Chinese mainland, so Haoyang’s parents had to look elsewhere for solutions.

I soon found a Menkes support group online. After joining, I learned that copper histidine is the only thing that works for this disease, but when I asked where I could buy it, everyone said you couldn’t. I saw a shared document in the group mentioning you can go to Taiwan to get the medicine, but this was during the pandemic, so we couldn’t go.

With a trip to Taiwan out of the equation, Xu’s doctor recommended that he try a therapeutic cocktail that supplemented several trace elements. But after two weeks, his child’s indicators still hadn’t returned to normal.

It appeared that copper histidine was still the only thing that could save his child’s life. There was no way to purchase copper histidine directly, but could there be another path?

By then I had already read many papers. I was researching all over the place. Whenever I had a spare moment, I would take out my phone and look up facts. I translated and checked everything. The biggest problem was I just didn’t understand the papers at all, because there were all these proper nouns I had never encountered before. I had to look them up one by one.

Of course, I only had so much time. I’d read maybe 10 papers, so I already knew how copper histidine was synthesized. The papers had all the steps written out, so I thought, if we have the method, we might be able to find a drug manufacturer to help us produce the compound.

I also tried to bring together people from the support group to get a manufacturer to produce the medicine, but they had their doubts. They didn’t think the facility would do it. Maybe it’s because someone had tried it before, but at any rate they didn’t think a drug manufacturer would help individuals develop a medication. Pretty much everybody said it was impossible: “You’re so naive; to get a manufacturer to do it involves so much time and money; nobody would go through with it.”

But Xu Wei had no other alternative. The only way he could save his son was by trying what everyone else said was impossible. He found a drug-production company online and was able to get in touch, eventually flying to Shanghai to talk to them in person. It was only then that he learned exactly what the support group had meant when they said, “You’d have to put in so much time and money.”

When I arrived at the Shanghai facility, I talked to the staff and discovered that in their plans for us, they were going to follow a standardized process to the letter. With that kind of process, you have to run a lot of trials first, and the drug regulations are also quite complex, so it takes quite a long time. The facility told us that the stage-one trials alone would need six months; for a medication to go from a chemical compound to an approved pharmaceutical, even three to four years is considered fast. And it’s extremely expensive: It could cost tens of millions of yuan to do all of the experiments. So I had to give it up.

It’s not just Menkes—many other rare-disease patients are in a similar predicament. Medications for rare diseases are often nicknamed “orphan drugs.” For one, because the incidence rate is low, the profit potential is slim, so drug manufacturers are not very enthusiastic about developing these drugs. For another, even if a drug is produced, the prices are often sky-high in order to recoup the research and development costs. Last August, the market price of injections for another rare disease, spinal muscular atrophy, rose to 700,000 RMB a pop, and this sparked heated online discussion in China.

Just as Xu was at his wits’ end, he discovered the existence of so-called “shared laboratories,” where individuals could rent out space for their own experiments or commission lab researchers for specific projects. There, he was able to recover his hopes of producing copper histidine.

-3-

Taking a big risk

I wanted to find a lab as quickly as possible, to see if we could go through them to synthesize the medication. Later, we found a medical corporate park that had a central laboratory serving the drug companies based there; the lab was also open to outsiders. An employee told me the lab space could be rented out, or we could leave the experiments to them: they would supply the employees and equipment, and run the procedures on our behalf.

After finding the shared lab, Xu had to pay the lab personnel and source the raw materials for copper histidine himself. Compared to working with a manufacturer, the shared lab offered quicker results at substantially lower costs. The copper histidine could be synthesized in just a day or two, with total costs coming in under 20,000 RMB. Xu’s first bottle of copper histidine was made in that lab.

Xu finally had medicine for his son. At home, he would pull faces at Haoyang; when the boy smiled back, the simple expression brought Xu a deep sense of gratitude. Haoyang’s ability to smile meant that the medicine was working, and his son’s life could extend one more day.

But Xu’s joy was short-lived. Though the cost of producing the compound in a lab was only a fraction of the tens of millions required to work with a manufacturer, the daily injection was still a significant expenditure for one ordinary household.

Copper histidine has a shelf life of only 56 days, so if I go to Shanghai to make it, I’d have to go about once every month and a half. After calculating the production costs, I worked out that the cost of going to Shanghai once was enough to purchase all the equipment needed to produce the medication, so I decided to buy the lab equipment and make it myself.

In August, I went to the lab and observed the entire process for producing copper histidine, so I knew it actually wasn’t very difficult. I bought everything I needed, including the high-pressure autoclave, the clean bench (fume hood), the magnetic stirrer, the pH testers, water purifier, oven, and so on.

I learned the basic procedures through an online course, and also recorded the whole process on video when I visited the Shanghai lab. I kept re-watching the clip, following the procedure step by step: first the sterilizing and weighing, then the dissolving and mixing, then testing the pH, and finally bottling.

I tested the copper histidine on rabbits first to see if it caused them any harm. The rabbits were unaffected, so then I tested it on myself, and saw that there also weren’t any side effects. Only then did I do the injection for my child.

I have a fair amount of confidence in the copper histidine I made, unless everything in the research papers was false. I’d looked at so many papers, all from reliable sources, so I was fairly certain it would work.

Xu followed the research to the letter, and even though he’d done safety testing, his family and the other Menkes parents were highly skeptical. Lacking the layers of verification that drug manufacturers employ, lab-made compounds fall outside of government safety standards, so Xu may have put himself in legal jeopardy. What’s more, everyone doubted that a dad with only a high school diploma could produce an effective cure for his child.

They all thought it wasn’t possible. They were worried sick. “If you make it yourself, it’s never going to be proper medicine, and not just that, it’s going to be used on people, and not just anyone, but a child.” They didn’t get it—they thought it was crazy. Everyone I know said it couldn’t be done, that it wouldn’t be so easy. A few of them came right out and said, “I bet you won’t be able to do it.”

But I felt that if there was any hope of success, I had to try—I couldn’t quit before I started. If I do my best and fail, then I can stop. I’ll stop trying only when I can’t go any further.

A week after the first injection, we went back to the hospital to get Haoyang’s ceruloplasmin and serum copper levels checked, and found that these indicators were now in the normal range. I had confirmation that my method worked. I thought, “I’ve finally done it, I can finally treat his symptoms.”

Even with his indicators improving, Haoyang’s EEG still displayed some abnormalities. The copper ions carried by copper histidine can’t cross the blood-brain barrier, presenting an obstacle to brain development. Xu found additional research indicating that copper irismol was another compound used in treating Menkes disease: This compound can carry copper ions into the brain. Of course, its manufacturing costs and complexity are proportionally higher.

But Xu didn’t have the time to weigh the funding, safety, legal risks, and other factors. Instead, he was thinking that his home lab already had the equipment needed to make copper irismol, and that this might be the only way to support Haoyang’s cognitive development. He decided to take action.

-4-

Addressing the root cause

After we had used copper histidine and copper irismol together for three months, we went back for a follow-up EEG. The test found that Haoyang’s abnormal wave patterns had disappeared, and he was also more active. We were so relieved. We had halted the progression of our child’s illness, which I would say is no small accomplishment.

Ever since his son received his diagnosis, Xu has been following the latest research on Menkes. His own projects have also grown more complex: The leap from synthesizing copper histidine to copper irismol far surpasses the scope of his education. Xu believes he’d always had a thirst for learning, which was further stimulated by the life-and-death situation he faced.

Xu has been investing significant time and energy in exploring new treatment methods. Recently, he has been focusing his attention on gene editing. Copper deficiency will gradually lead to connective tissue abnormalities and organ failure; although organ failure can be treated in isolation, this doesn’t address the root cause of the disorder. The patient will have to go through treatment over and over, until their body can no longer withstand it. Only gene therapy can cure this disease, by replacing the mutated gene with a normal one.

Back when I first started looking at research papers, I learned that copper histidine wasn’t a cure for this disease—it can only alleviate some symptoms. Some of the Menkes papers mentioned gene therapy, so even then I knew that was our ultimate direction.

After I finished making the copper histidine, I got down to doing the groundwork for gene therapy. I made thorough readings of papers on genetic treatments for Menkes in order to understand the methods and principles involved. This was very challenging: First off, you have to understand cell biology. You have to understand what protein structures mean. You have to understand gene transcription, how ribosomes function, the composition of codons for amino acids, how synthesis works, the principles of gene expression…

As time went on, I slowly made sense of the mechanisms behind gene therapy. Then I started looking into the companies that do gene synthesis. I split the process into individual steps to see which parts of the process can be done by outsourcing to companies and which parts I need to do myself.

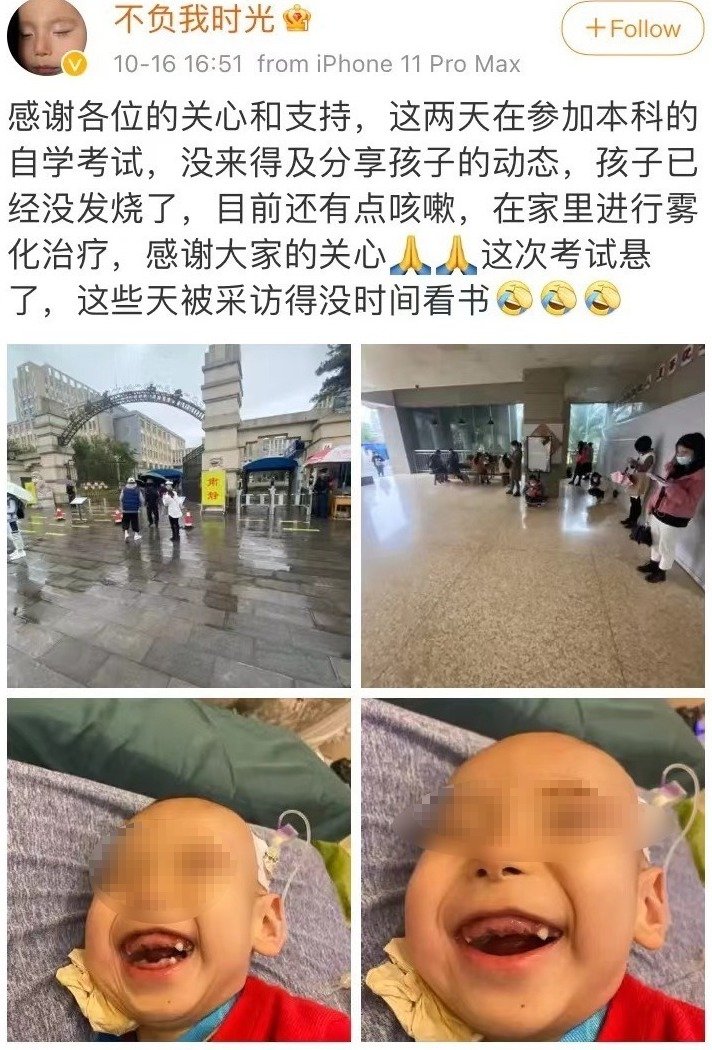

In October, Xu’s story received extensive coverage in the news, and “I’m no chemistry whiz, just a father” became the top trending hashtag on Weibo. Xu received a lot of attention as a result.

Now, aside from his busy research and production schedule, he also has to set aside time to give interviews and respond to inquiries from other parents of children with rare diseases. His foray into drug-making was a last recourse that shouldn’t be imitated, given the underlying risks. But Xu has shared his story over and over because, as he says, “There always has to be someone to bring an issue to light and make everyone see it—only then can that issue be resolved.” He hopes the public exposure can help him reach more experts, bring attention to the plight of rare-disease patients, and promote further research.

I never thought I’d get so much exposure. Now, every day there are reporters coming to interview me, along with enthusiastic online supporters and gene industry professionals who want to help. I’m pretty touched that people are finally learning about this disease and want to help us.

There are around 20 children remaining in the support group. On the whole, they aren’t doing very well. Just today, I found out that two of them are in the ICU.

I hope that with all this attention, we can get the funding we need for a cure, because whether you want to do gene therapy or more advanced gene editing, you need money for all those experimental procedures. I hope this money can be used toward a cure for Menkes, to give us all hope.

Translated by Nathaniel J. Gan