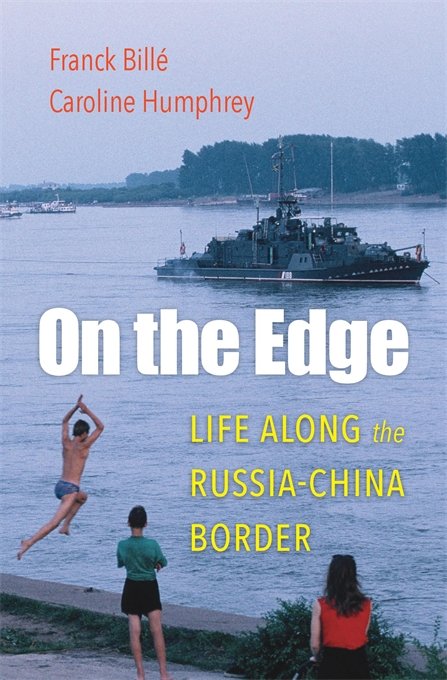

Franck Billé and Caroline Humphrey’s “On the Edge” portrays how China’s rise reshaped the reality of the people living just across the river

Far in the north of China, river waters wend through swamp and taiga, swerving and rearing like a black dragon to guard the 4,200-km border between Russia and China. The rivers Amur (Heilong), Argur, and Ussuri form the contentious edge of two ancient empires, each profoundly changed by the 20th century and quite different from one another today.

As we learn from On the Edge: Life Along the Russia-China Border, a new work of popular anthropology written by Franck Billé and Caroline Humphrey, this border marks not only the porous edge of two political and social realities, where people trade, smuggle, travel, and marry. It divides different imaginaries as well.

“Imaginary,” as a noun, is left undefined by the authors, but corresponds to a population’s beliefs, everything used to imagine and interpret reality. It’s a lens that allows the authors to sidestep whether their border-dwelling subjects’ ideas about identity, borders, and their divergent histories match reality. Often, they do not.

The use of the term hints at the seriousness of the research, conducted by two experts in the region. Caroline Humphrey, a grand dame of British anthropology (Queen Elizabeth II actually dubbed her a Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire in 2011) has studied Siberia and the surrounding regions since the 1960s, producing abundant volumes on Inner Asia from her posts at Cambridge University.

While Mongolia and China’s Inner Mongolia region have a special place among her bibliography—evident when On the Edge examines the shamans of the borderlands—her research has a far stronger footing in the post-Soviet states than in China. Neither her prior works, nor the explorations of this volume, take us very deep into Chinese imaginaries.

The same is true with Humphrey’s co-author, Franck Billé, program director at UC Berkeley’s Tang Center for Silk Road Studies. His work with Humphrey on a three-year border project, part of his doctoral studies at Cambridge, provides much of the direct research appearing here.

Whether by temperament, training, access, or something else, Billé too tips the balance of his attention onto the Russian side of the border. His earlier books, largely focused on Mongolia, regard China from the outside, from the perspective of neighbors and rivals. The same is largely true in On the Edge, and the perspective of the people of China remains mysterious.

The book is a collection of essays drawing upon multiple experts, concatenated as a hybrid work of descriptive non-fiction. The primary field research comes from the authors’ trips to the Russian-Chinese border between 2012 and 2015. This is supplemented with a dizzying hodgepodge of voices, from interviews conducted by other anthropologists, to the pronouncements of geographical and architectural theorists, down to the perspective of “Ivan, an economics professor at Amur State University,” quoted without a surname on page 254.

The research conducted by the authors is valuable and fascinating, especially when the book displays drawings of Blagoveshchensk and Heihe, two border towns divided by the Amur River, which gives its name to China’s Heilongjiang province. These illustrations, composed by Russian college students during interviews with the researchers, offer readers a vivid way to see how they imagine the contrasts between the two cities. Learning about their long-engrained biases toward their Chinese neighbors can help nudge us to reflect on our own. In that Russian imaginary, the people of China are rapacious for living space and natural resources, with paltry culture, little depth, and a transactional worldview.

As to the Chinese imaginary, the authors’ research is more limited. Interviews with entrepreneurs and a case study of a cross-border jade export business reveal an eagerness to develop the natural resources of the border region, build a thriving tourist base, and continue the trade that allowed the border region to grow so quickly. The Chinese residents seem to lack the biases of their Russian counterparts, but those might be revealed if more in-depth interviews were available.

The authors write early on that this border is a confrontation of “two entirely different worlds” and they demonstrate that, to a point. In their analysis of the political economies of both sides they argue convincingly that Russia’s top-down hierarchy is less dynamic than “the Chinese propensity for real (albeit authoritarian) participatory assimilation” which they cite in their coda. But as the authors consider individual behavior, what emerges are more similarities than differences: People on both sides are pragmatic, transactional, and a bit a-legal as they strive to get ahead.

The more fascinating take-away from On the Edge focuses on the change we’re all living through. In the residents of Russian Blagoveshchensk, who dismiss Chinese Heihe’s brightly-lit skyscrapers, they identify a “global imaginary unwilling to take China’s rapid pace of development as genuine.” The residents’ imaginations have not caught up with the reality of China’s quick ascent to the world’s second-largest economy. The result is that nearly every young person in Blagoveshchensk expects to somehow profit from China, while the population at large still considers China the little sibling to Russia, dependent on its guidance even as the former Soviet state has been outmoded in nearly every way.

It’s telling that residents of Blagoveshchensk, like the rest of Russia’s Far East, describe themselves as nearly abandoned at the end of the earth, even as the most dynamic economy in the world buzzes right across the river. It’s still not real to them.

As popular history, showing how history plays out in people’s minds, the book succeeds. As academic analysis, it’s wanting. There’s just too much equivocation (the frequent use of “perhaps”) and the disparate narratives the authors weave lack clear authority. Too often an expert is cited once, just to make a point, and is never heard from again.

The same breezy treatment is applied to intellectual concepts, as when the authors introduce the distinction between “law of nature” and “natural law” at the border. After a page or two, the concepts are discarded as the narrative moves on.

Perhaps the worst example comes in the final paragraph, when they introduce the concept of “friction” to describe “the generative energy produced through the physical and involuntary coming together of two different cultures.” This would have been a useful tool to structure earlier descriptions of border interactions, but it arrives too late to the party and the guests have already gone home.

But the high-minded conclusion from the coda of the book rings true: “The diversified picture that emerges in this book provides cultural context crucial to triangulate the significance, reverberations, and limitations of larger geopolitical shifts.” Their somewhat disconnected chapters present the broad view of some of the peoples living along one of the longest borders in the world. The book can help the reader who’s looking to understand Moscow as it turns to the east, or Beijing as it continues its Belt and Road Initiative.

On the Edge may not have all the answers, but it gives voice to people who’ve witnessed China’s incredible rise from just across the river, and portrays how China’s economic might has reshaped their world—in reality and imagination.