Contemporary art battles to find a place to grow in the face of regulations and rising property prices

About an hour’s drive to the east of Beijing, the village of Beisizhuang bears little resemblance to the bustling skyscrapers of the city. Tangles of cables hang low across narrow alleyways of gray brick walls, and there is little sound aside from swallows chirping and bees browsing plots of vegetables.

But this, and several other villages in the township of Songzhuang, are the site of a last stand. Located on Beijing’s far eastern outskirts, adjacent to the province of Hebei, the township was at one time part of a proud tradition of avant-garde artist communes—places where contemporary artists could find cheap accommodation and develop their creative niches in social freedom and rebellion. But as regulation and gentrification have tamed China’s wider contemporary art world, so are these communities becoming tamed too.

That the village will be redeveloped is “everyone’s biggest worry right now,” artist Song Yonghong, a veteran painter and a former art teacher, tells TWOC in his high-ceilinged studio within Beisizhuang. In 2015, Beijing’s municipal government announced it would relocate to Tongzhou district, about five kilometers away from Beisizhuang. The move officially began in January 2019.

Song had arrived in Beisizhuang as a refugee of urban development, with “nowhere else to go,” in June 2017. The municipal government had demolished another village he was living in to the northwest of Beijing, part of a city-wide clean-up of shabby migrant settlements.

The bulldozers also came in the same month for Heiqiao, the legendary artist commune in Chaoyang district, forcing residents like Yang Song to flee. “Songzhuang is the last place [in Beijing] where there are many artists gathering,” he tells TWOC.

They aren’t the only ones who were given no choice. In 2010, there were over 20 artist communes in the city, with populations ranging from a handful to tens of thousands. Dozens dotted around the 798 Art District (an industrial compound revamped into a high-end collection of galleries and boutiques) were cleared in 2010, as well as the so-called “iron ring” (Huantie) to the city’s northeast.

But if these are refugees, they’re certainly well-treated ones. Both Song and Yang rent big, well-heated new lofts that stand out from the smaller bungalows of their local neighbors. For one veteran Beijing gallerist, who wished to remain anonymous, the community has grown indulgent. Though he believes Songzhuang still harbors some talent, it is also “a piece of incest, as the artists rather tell each other how good they are and drink together, instead of criticizing each other and pushing each other to grow…So whatever opinion comes out of Songzhuang, I do not take it seriously.”

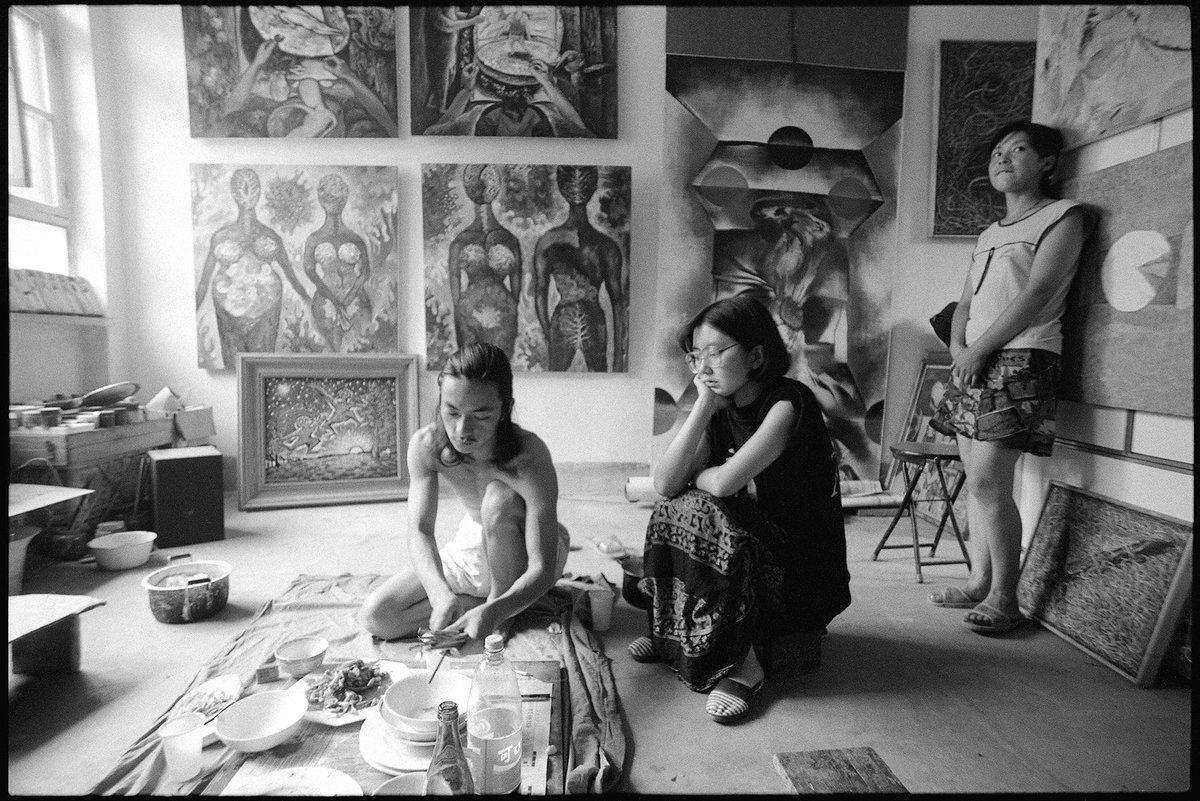

There is a certain prestige to Songzhuang, given its heritage in contemporary art history. Communities like the Xiamen Dada and the “Southern Artists Salon” in Guangzhou through the 1980s, or Beijing’s Yuanmingyuan commune of the 1990s, were the origins of Chinese contemporary art, representing “the inner desire of people for freedom in artistic creation,” according to Song.

They railed against the methodical state-sponsored system from the days before the 1978 reforms. “If you had a talent, you were recruited into your danwei propaganda department,” says Li Mingzhi, a photographer and painter who worked during the early 1970s. Li was commissioned to create photography that celebrated industry and the labor force. “I don’t think it’s creative work,” remembers Li. “It was just my job.”

The 1978 reforms loosened the policies that had tied individuals to their local danwei, or work-unit, for work and residence. Workers—including artists—began flooding into cities. Physical communities on the outskirts of the city helped contemporary artists break from the system. The village of Yuanmingyuan, about an hour’s bus ride from Beijing’s center near the Old Summer Palace, attracted artists from all over China who had quit or suffered job losses in the shrinking state sector. They needed the cheap rents of the village’s spacious, unheated red-brick huts, and were looked down on by urban residents as unemployed mangliu (“drifters”), but the lifestyle still proved appealing: “I actually envied them,” Song, at the time a university art instructor, remembers feeling of his friends in Yuanmingyuan. “They could draw every day, whereas for me there were times when I wanted to draw but had to teach students.”

Their poverty was exceptional: Ying Li, the artist dubbed Yuanmingyuan’s unofficial “village head,” told the Chinese journal Master Oriental Art that one group of artists banded together and used a female dog to lure a male dog, which they then caught and cooked into a stew.

But the commune was the victim of its own success. As foreign art dealers began visiting, rent prices soared and, some original residents say, talent levels began to decrease as more were attracted to the commune. The Beijing municipal government ordered the residents to disperse in 1995, even placing some in detention centers. Some artists believed the compound had been cleared due to the potential for unrest, located too near to the university compounds of Tsinghua and Peking. But author Xiong Yan also notes in his book Yuanmingyuan Artists’ Village that there was a city-wide clean-up of migrant villages at the time.

Yuanmingyuan’s informal successor was the village of Xiaopu within Songzhuang township. In 1994, influential art critic Li Xianting (known to the press as the “Godfather of Chinese contemporary art”) and a selection of Yuanmingyuan’s more successful artists, were attracted by remoteness and low rent rates. The commune adopted a low profile to avoid attention from officials and opportunists.

The work created in Yuanmingyuan and Songzhuang was fresh, a revolt against the trends of the 1990s. “Cynical Realism” was a brightly-colored take on the powerlessness of the individual in a collective society, pioneered by the “laughing faces” of painters Fang Lijun and Yue Minjun. The “Gaudy Art Movement” was a tide of overly-garish art that provided ironic commentary on “the powerlessness of art to impact on the pervasiveness of consumerism in today’s reality,” according to Li Xianting.

The work of Yuanmingyuan-Songzhuang residents Fang and Yue became the cornerstones of the “Cynical Realist” art movement. By 2007 the latter’s work was selling for 4 million USD, TIME magazine reckoning that “if the big picture question of our time is what to make of China, this is the man to paint it.” Indeed, there was little room for anything else, as the pair and a few others of Li’s circle “came to be recognized as the representatives of contemporary Chinese art,” writes Dr. Meiqin Wang, a researcher on Chinese contemporary art at California State University, Northridge.

Songzhuang’s early days were similarly bohemian. Performance artist Cheng Li drew quite a crowd for his “Second Nude Day,” floating in nearby Chaobai River whilst completely naked. Song says this would be unthinkable today—“the Beijing municipal government is right there,” he says, pointing out of his window.

Beijing police began to regulate the commune before the 2008 Olympics. In 2011, Cheng was arrested and detained for a year for inviting 200 professionals to view behavioral art on the roof and in the basement of Songzhuang’s Beijing Museum of Contemporary Art—which consisted of him having sex with a female partner.

Ten years earlier, in April 2001, the Ministry of Culture had banned all “performance or display of bloody, violent, and obscene subjects, as well as presentation of human reproductive organs or other pornographic acts that are harmful to society.” But away from performance and presentation in public institutions, artists could still create and sell works that would be frowned upon. For example, galleries in Beijing’s 798 are required to submit lists of all works in an exhibition to the Chaoyang District Cultural Office. But “this is more a routine formality,” says Brian Wallace, director of the Red Gate Gallery in Beijing. “All the gallerists know full well what you can put up on the wall in the public spaces of each gallery. Out the back it is a different matter.”

The village of Heiqiao was the natural successor to Songzhuang and Yuanmingyuan. From 2006 to 2017 it was the largest commune for grassroots artists in Beijing. Poverty and stigmatization were the norm; the village’s party secretary referred to the artists as diaosi (“losers”) in a 2016 interview with a researcher from the University of Amsterdam.

But that didn’t matter. “It was like a utopia,” says Yang. “A lot of people are nostalgic for Heiqiao: because it was very wild, you could do anything.”

Take Heiqiao Night Away, a tiny shack where any artist could spontaneously set up an exhibition without submitting any paperwork. The rules were simple: Don’t destroy the building and don’t break any laws. “One week [in 2013] for his exhibition, an artist just hired all these villagers to stand around the building to prevent people from going in,” remembers Yang. The project snowballed as each artist tried to “disrupt” the piece. “Finally somebody got a bulldozer and tore down the building, and then we all sat on top of the rubble and drank.”

“Just living there every day, I’m in a creative mood,” says Yang. His creations are inspired by the vibrancy of speed, based on the experiences of his own bike journeys with Heiqiao friends.

Squeezed by the state on one side, today’s commune artists face the forces of the market on the other.

Originally providing an alternative career path to working as an artist within the state system, contemporary art has created an establishment of its own in the form of auctions, art fairs, and galleries in China’s biggest cities, particularly Beijing and Shanghai.

Despite a downturn since the 2008 recession, China’s contemporary and post-war art market has tripled since 2009, according to a report compiled by Art Basel (a major international art fair) and global financiers UBS. Indeed, 35 percent of the global contemporary art market’s value in 2020 came from the Chinese market, on par with the US (36 percent)—and that’s excluding any works that are sold untaxed and unreported.

It’s now possible for artists to make a lot of money very quickly—Beijing-born ink and calligraphy painter Cui Ruzhuo has topped the Hurun China Art List for six years in a row, making 657 million USD over that time. Collectors are prepared to spend big if “the success of an artist is ‘certified’ by famous collectors buying this artist,” explains the veteran gallerist, “once the price is already rather high.”

This new establishment has even begun to absorb the state system. In 2014, an “Experimental Section” was added to the National Art Exhibition (a stepping stone for artists becoming members of the Chinese Artists Association), featuring contemporary artists like Wang Yuyang. “Young artists nowadays, if they are not from wealthy families, will try to get a teaching position in the universities…in order to still work in the field they like” and not being solely dependent on art sales, explains the gallerist. To get these positions “they have to work closely with the Party Committee of this university. If you now check who are the high-ranking professors in the most famous universities, you will see that there are quite a big number of the most respected [market] artists of China.”

Money also breeds imitation. In October 2020, artist Ye Yongqing, a professor at the Sichuan Fine Arts Institute whose works have been sold at international auction for up to 1 million USD and collected by the likes of Bill Gates, was summoned before the Beijing Intellectual Property Court after being accused by Belgian artist Christian Silvain of repeatedly plagiarizing works by him which sell for a maximum of 17,000 USD, as early as the 1990s. Living in Beijing in 2004, artist Xue Tao remembers many imitating the styles of those fetching high prices on the global market and being exhibited abroad. “Chinese artists were all chasing after the ‘big face paintings,’ paintings in the style of Yue Minjun and Fang Lijun, with kitschy colors,” he said in an interview for TCGNordica Arts Center, a Scandinavian gallery based in Kunming. “Art made in this way saw certain market returns, and I was sometimes swept up in it too.”

The gallerist believes this is partly due to the university system: Entry to Chinese art universities requires imitation over creativity, “so you see a lot of students will paint in the style of their teacher.” By contrast, many of the pioneers of Yuanmingyuan had not gone to art school: Yue Minjun had worked on an oil rig and as an electrician, practicing painting on the side. Yet even Yue himself is now limited to painting faces, telling Phoenix TV in an interview he feels “shackled” to them. “To make money, the market forces you to paint faces.”

Rising rents for studios has been a problem in factory districts converted into artist spaces, attracting big money and property developers. An increase in the industry’s value means rising costs, pressuring those at grassroots level. This is what happened to Xue Tao, who moved from Beijing back to his home province of Yunnan in 2012. “The reason was simple: I couldn’t afford to keep paying the rent.”

But the state likes the profitable side-effects of art. Known in art circles as the “Bilbao effect” (after the Guggenheim Bilbao’s raising the GDP of the run-down Spanish industrial town), pre-planned artistic communities and galleries can be used as a tool of urban regeneration. In 2011, the Xuhui district of Shanghai began to re-develop a run-down industrial area near the 2010 World Expo site into a “cultural corridor,” now boasting galleries dotted amidst green spaces and a rent rate of 19,000-21,000 RMB per month for a two-bedroom flat in the near vicinity.

In 2006, the Beijing government declared both 798 and Songzhuang a “cultural industry base.” It attracted businesses, and allowed farmers to raise rents. Songzhuang’s streets now boast wine shops and clean sidewalks, and artists, far from being treated as diaosi or mangliu, are profit: “After all these years [the locals] do understand it and rent houses to us,” says Yang. “It’s relatively harmonious.”

Likewise, China’s wealthiest have discovered art as a way (as the gallerist puts it) to “launder money, curry favor with the authorities, and show off,” leading to a boom of private museum spaces. The He Art Museum in Foshan, opened in October 2020, is the brainchild of He Jianfeng, son of Midea Group founder He Xiangjian, the sixth richest Chinese person on the Forbes billionaire list (at the time of writing). 2020 also saw the opening of X Museum in Beijing, advertising itself as a space to harbor young and striking contemporary artists. One of the joint founders of the project is Theresa Tse, who inherited her father’s 18 billion USD pharmaceutical company, Chinese Biological Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd.

Today, Yang limits his rebellion to sneaking out of town during lockdown on his motorbike, and building a small swimming pool in his front yard. “Other than that, I like to rearrange my living space,” he says, pointing to a hole he made in his living room wall.

What’s Next for China’s Once-Thriving Artist Communes? is a story from our issue, “Call of the Wild.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.