An artist’s pilgrimage to find relics of the Northern Song in rural China

“Where is the head?”

“Kid, if we knew that, don’t you think we’d have put it back on?”

Mr. Li coughs up a ball of phlegm and fumbles with a pack of cigarettes. We sit under the shadow of a looming, gray monolith. It surges upward through the soil, a set of immaculate robes enveloping a towering, slender figure. In its hands rested a tablet. For nine-hundred years, this headless official had diligently stood in line, waiting patiently to deliver his report to the Son of Heaven. Li, the security guard at the site, eventually tells me that the head had fallen victim to the Red Guards during the 1970s; it was turned into gravel.

The headless minister was one of roughly two dozen statues set in this unassuming wheat field. Together, they form a spirit way—an elaborate stony procession common at the entrance of high-end ancient Chinese tombs. These embittered sculptures come together to guard the tomb of Emperor Shenzong of the Song dynasty (960 – 1279), an immense, sprawling mound of earth just to the south of us. Seven Song emperors lie buried here outside Gongyi, a city of 800,000 people in central Henan province, largely undisturbed for 1,000 years.

Li eventually wanders off and leaves me alone. I then snap into gear, remembering why I had come. I pull out my brush and start to paint, eager to catch the last rays of the sun undisturbed. I only had two more days in Gongyi and wanted to make the best of my trip.

The tombs of the Northern Song dynasty (960 – 1127) had been a personal “bucket list” item for years; for a devoted lover of Song history and culture, few other places can be such a worthy location of pilgrimage.

Furthermore, the tombs at Gongyi remain largely unchanged since the time they were built. Most of them exist today in the middle of farmer’s fields or amid jungles of weeds and bushes—their spirit way statues half-concealed underground after a millennium of neglect. Each of these statues was unique—no one the same as another—hence why I wanted to see as many as possible.

In a country which prides itself on meticulously curating and restoring the past, it is rare to find so much as a rooftile out of place in most national heritage sites—yet here in Gongyi thousands litter the ground, being turned up by the farmer’s hoes every year. Of the seven emperors buried here, only two have had the privilege (or perhaps the affront) of having their tombs heavily restored. A local driver from Gongyi, with the surname Zhang, drove me to each of the tombs over three days, which were situated around the outskirts of one small village outside the city. The second tomb I visited was that of the “Martial Emperor,” Taizu, who established the Song state and chose Gongyi for his mausoleum.

During Taizu’s reign, China was unified for the first time in almost a century—a new golden age had begun. Legend has it that Taizu is the only emperor in China’s history to have chosen his burial spot by use of an arrow; fired, by most accounts, from his palace in Kaifeng, and landing here in Gongyi, some 80 miles away.

Apart from picking out his own tomb, Taizu dragged his father’s remains here from Kaifeng posthumously, honoring him with an imperial burial. The tomb of every subsequent emperor in Taizu’s line, up until the empire lost northern China to the Jurchens in 1127, are scattered around the appropriately-named Balingcun (“Eight-Tombs Village”), along with a good number of smaller ones for empresses, princes, and other members of the imperial family, as well as ministers of repute.

It is due to Taizu alone that Gongyi’s sprawling tomb complexes exist today—and perhaps no surprise that his is one of the largest. As I make my way around Balingcun, discovering tombs in various states of repair, I find myself the only tourist around. Aside from the city’s Cultural Relics Protection Unit having recently banned farming around the tomb, not a great deal has happened on the site. Eventually, I made my way to the tomb of Emperor Zhezong, which—Li had told me—was the best preserved. It did not disappoint.

Around 60 immense statues, ministers, soldiers, and beasts form the spirit way, facing each other in two firm rows, separated by a grand entryway. Most of these statues, which had originally been half-buried, had been dug up and re-set at ground level on subtle concrete plinths which hid behind the wheat harvest. Aside from this simple fix, it was largely untouched and intact. I wondered whether it had averted the attention of vandals simply due to the fact its occupant was a relative footnote in Chinese history.

Emperor Zhezong had shown early signs of promise as a young ruler. Life then got in the way; he died of a sickness, aged 23. His younger brother appears much more frequently in textbooks—his reign would mark a turning point in China’s history.

Emperor Huizong enjoyed 26 years of rule over the Song Empire. The emperor—known today as a remarkably talented artist and calligrapher—favored hedonistic pursuits over matters of state. In 1127, the invading Jurchens stormed the Song capital, Bianjing (modern day Kaifeng), and razed the city. They destroyed innumerable works of art and treasures, and Gongyi, along with Kaifeng, fell to the Jin dynasty (1115 – 1234). One of the most devastating impacts of the Song’s defeat was on ceramics: Many of the highest-quality porcelain kilns were destroyed en masse, including the prized glaze of all (and supposedly Huizong’s favorite), ru ware, of which less than 100 pieces are estimated to have survived intact.

Huizong died—along with most of his family—far from home in enemy captivity in what is today’s Heilongjiang in the far northeast—dethroned and disgraced. A surviving scion of the court managed to flee and established the Southern Song, but none of Huizong’s successors ever managed to retake Gongyi. The vestiges of the old empire were pushed further and further south until the Mongol-led Yuan dynasty wiped them off the map in 1279, and Gongyi was left to rot—the Song tombs gradually forgotten.

Though the exact contents of the imperial tombs will now never be known, it was recorded that the Song emperors were buried with immense amounts of gold, silver, jade, works of art, weapons, and other treasures. After sacking Kaifeng the Jin made their way to Gongyi and laid waste to the tombs. Though Emperor Zhezong’s spirit way survives in good shape, his corpse was dragged out and strewn across the ground, along with those of his relatives. As I wander around the fields, a miniscule glimmer of white peaks up from the ground. It is a tiny shard of Cizhou ware, a ceramic from Hebei popular during the Song. Multitudes of other ceramic shards dot the fields, being churned up every season by the farmer’s; along with rooftiles, bricks, and other pieces of debris. One need only take a glance at the ground to get a sense of scale of the destruction that took place.

The locals of Gongyi were purportedly not spared, either. When the Southern Song learned of the Jin’s actions and tried to retaliate to retake the tombs, the Jin doubled down—burning villages, smashing monasteries, and further desecrating burial sites. One account states that within a few years most of the imperial tombs at Balingcun were full of holes.

Today Gongyi is memorable for its unique connection to the Song Imperial family, but its history actually stretches further back than that. Du Fu—one of China’s most renowned poets—was born here during the Tang dynasty (618 – 907), and a small man-made cave marks his birthplace. Going even further back to the Northern Wei dynasty (386 – 534), Gongyi boasts an impressive Buddhist cave complex.

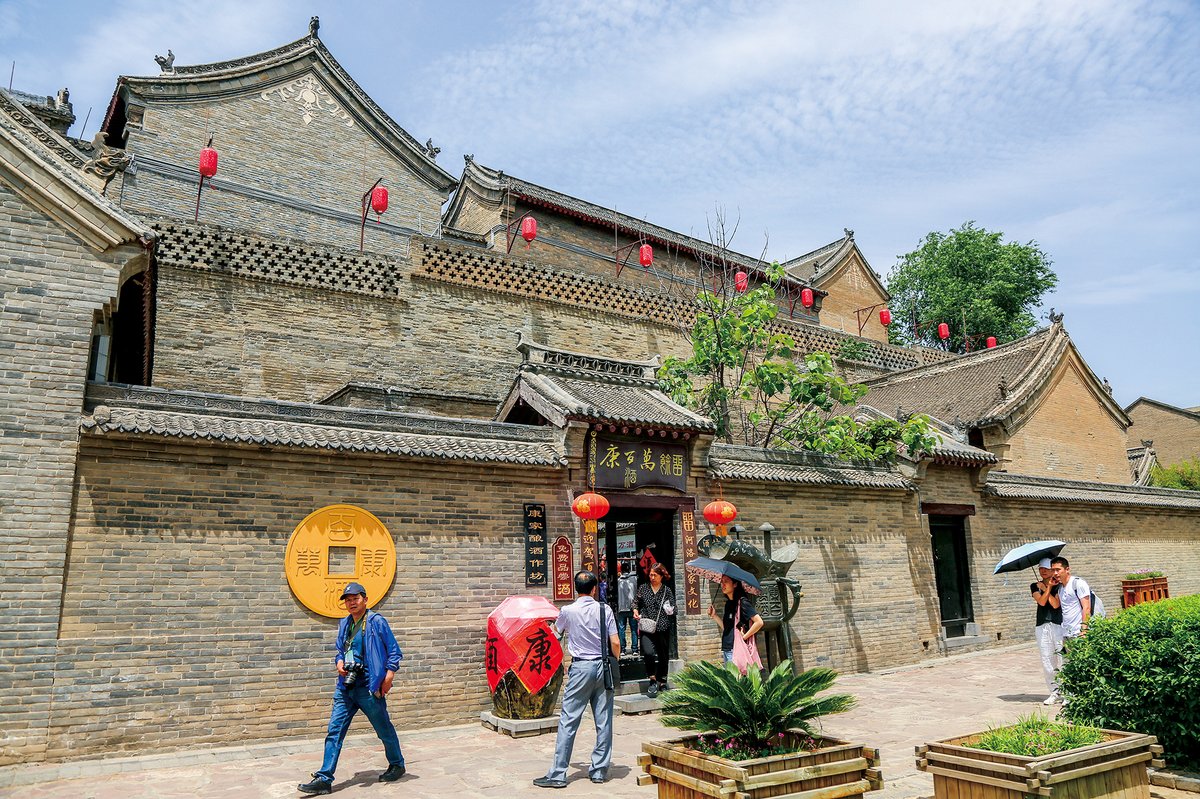

Stuck in the middle between two great ancient capitals—Luoyang and Kaifeng—Gongyi has never really stood out as a place of interest. Few tourists seem to come here, and most of Gongyi’s denizens seem to rely on agricultural or industrial work, as stretches of factories dot across the landscape Du Fu once grew up in. During the 2010s, however, Cultural Relics Protection Units renovated two of the tombs. Freshly-trimmed grass, immaculate pavements, and protective hedgerows are omnipresent. Visitors can access them during the daytime through shiny silver turnstiles, much the same as those in a zoo or theme park. The Cultural Relics Protection Bureau, I was told, plans to stop farming in further tombs this year—presumably heralding the same fate.

This paroxysm of modernity is, of course, a sad reality in most heritage sites. The Ming emperors’ tombs on Beijing’s outskirts, for instance, are probably glitzier today than they ever were in history; meticulously maintained and cleansed to the point of gaudiness. In 2013, there was widespread outrage when private contractors hired by a local Cultural Relics Protection Unit in Liaoning province overpainted frescoes at the Yunjie temple in Chaoyang that they were hired to “restore.”

There are also success stories. For example, the state-led restoration of the Qianlong Emperor’s retirement palace in the Forbidden City from 2002 to 2016, working with the World Monuments Fund. The project blended traditional craftsmanship and materials—using plaster with a traditional recipe of clay and pig’s blood, and reviving production in Anhui of a special mulberry fiber wallpaper—with modern science and conservation attitudes.

Few local people in Gongyi are really aware of the strange rows of statues dotted around these fields, let alone their significance. I had already walked for around 30 minutes and lost sight of where I had started until I came to a small field around half the size of a tennis court. A diminutive figure hunched forward with a hoe, beating away at the earth. I gave him a smile which was met with cautious reticence. He relaxed a little after I offered him a cigarette, and said he had been farming here for 60 years. All he told me—in a markedly thick Henan accent—was that the tombs were from the Song dynasty, and that he would retire next year. I asked him if there were any more statues around; a number, I had discovered, were hidden around the perimeters in obscurity. He shook his head and I stubbed out my cigarette.

“Wait! There is one. But it’s a little far away and difficult to access. There are lots of trees...”

“Tell me,” I urged.

He pointed toward a thick coppice on the horizon and gave me a few instructions. I thanked him and set off. Initially, I thought his warning had been an exaggeration—but this statue was out-of-the-way indeed. Fighting my way through a wall of thorn-laden branches, I finally pushed through into a clearing. Before me stood a lion.

The stone was a deep shist flecked with seams of white and black. Strands of hair from a delicately-carved mane curled and twisted around the neck, surmounting a terrifying, contorted face, staring at me head on. A millennium of rainfall had left its mark; lines of discoloration invariably streamed down the smooth, gray stone’s surface to create a most peculiar effect. In that singular moment I looked up and thought briefly that this lion was weeping in agony, tears rolling down its face: a lion mourning the death of an empire.

I pulled out my sketchbook for a final time, sitting in front of this monolith. In Xi’an and Beijing, imperial mausolea have become sprawling UNESCO sites; the legacies of past rulers safeguarded behind ticket booths, audio guides, and throngs of tourists. I was grateful that, in the 21st century, it was still possible to visit such a marvelous location quietly, and completely alone.

I got back to the car and took one last look at the rows of towering gray statues, mostly undamaged in this setting for almost a thousand years. I asked myself: Are these wheat fields really so objectionable? Huizong—the artist-emperor who shirked off state duties to appreciate beautiful landscapes—would probably contend that they are not.

Rediscovering Henan’s Forgotten Imperial Tombs is a story from our issue, “Call of the Wild.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.