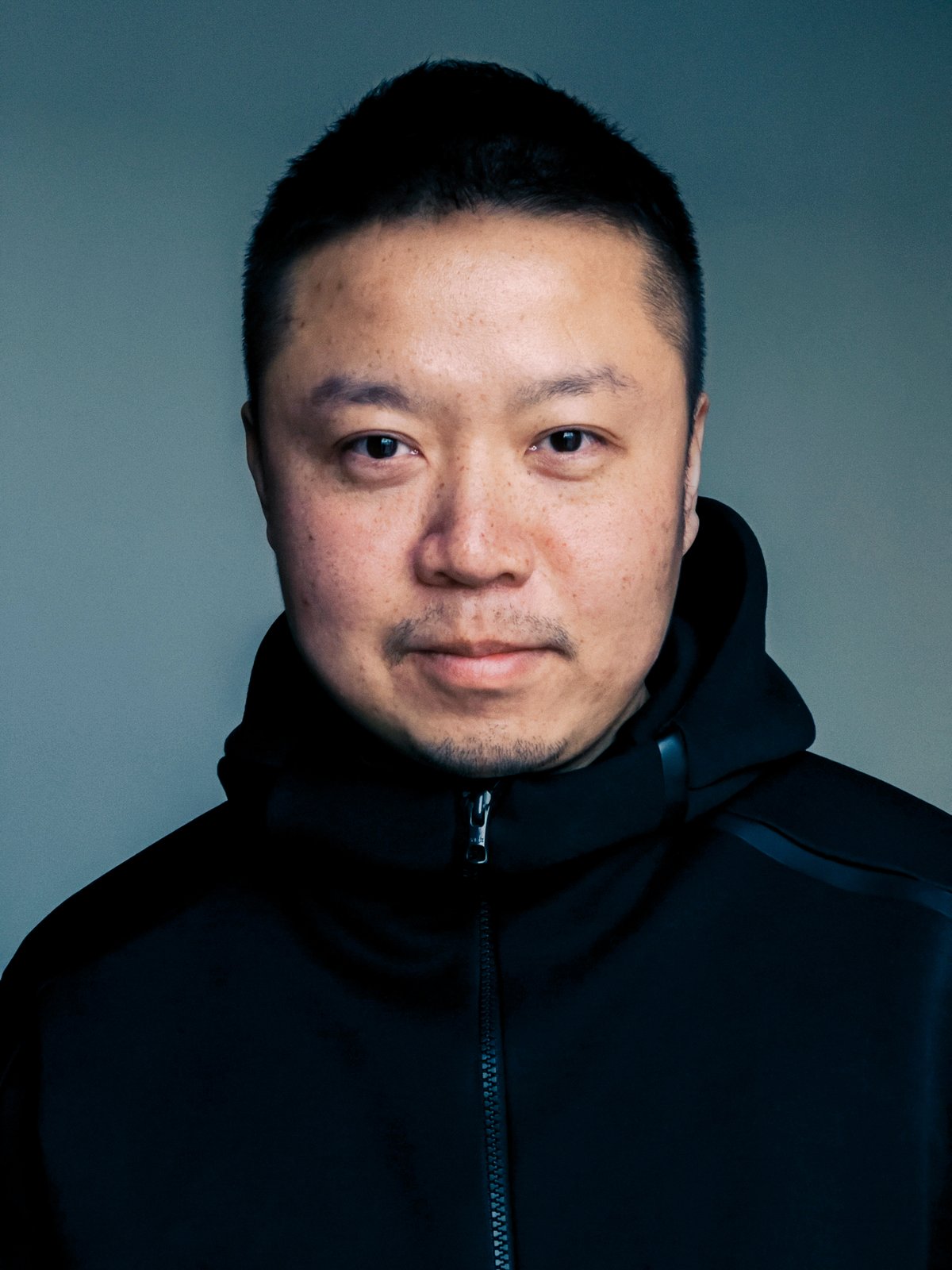

Artist Wang Tuo offers macabre meditations on China's past and present

Out of the darkness, the three giant screens illuminate the ghosts of past and present in a rolling triptych. Two show a bespectacled scholar of the “May Fourth” era hanging himself to the sound of an ominous backing choir, while the third has bass guitarists thrashing onstage to their own raging reveries.

The second screen now switches to a pond of lotus leaves. It is usually a symbol of virtue and restraint, but here represents pressure—a tangled thicket overwhelming the viewer and stretching as far as the eye can see, a skewed vision of infinite chaos.

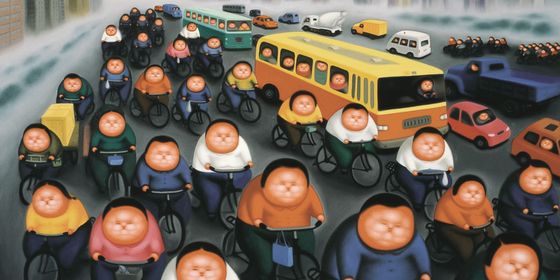

Welcome to the sinister and confusing version of China seen through the lens of video artist Wang Tuo, which harnesses the cold, unearthly power of “pan-shamanism” to transcend our hard dichotomies of past and present, fact and fiction, natural and supernatural. This self-invented philosophy allows Wang’s characters to engage in a dialogue with history, bringing disparate actions to bleed together in a collection of films collectively titled The Northeast Tetralogy, a project that began in 2018.

The work is being shown as a whole for the first time in Beijing by the UCCA from June 6 to September 5, alongside Wang’s other works. It is a serious business. Academic papers hang down from clipboards for the viewer to consult as they navigate through darkened rooms and Wang’s labyrinth of historical references. We’re a long way from the pink neon and inflatable octopuses of Cao Fei (the video artist most recently shown in UCCA’s main exhibition hall).

No mere passive entertainment, these are cerebral puzzle boxes to be untangled and solved. Take Tungus, a story from the Tetralogy. An ancient fable plays out from the Six Dynasties period (222 – 589), of a fisherman voyaging to the world of the dead. But this is in turn a story told to pass time as two Korean deserters wander through the snowbound wilderness in China’s northeast in the 1940s, encountering the mass murder of the 1948 Jeju Uprising, and eventually revealed to be ghosts. Elsewhere in this snowscape, a starved hermit scholar tries to communicate with a figure who keeps appearing in his dreams—martyred student Guo Qinguang, who hangs himself in protest at China’s fate at the Paris Conference in 1919. Whose story is it anyway?

The length of each piece requires considerable time investment—the Tetralogy alone takes two-and-a-half hours for a viewer to run through. Wang advises gallery-goers to immerse themselves in a few installations they find interesting, rather than try to see everything. “I think an exhibition is not the best solution for showing my works,” he tells TWOC. Whereas some artists create pieces based on how best to influence the audience, “I think 99 percent of my energy is devoted into the process of creation itself.”

But UCCA’s curatorial choices add further layers to Wang’s work, giving the viewer a strange sense of transcendence and detachment as they flit, ghost-like, from room to room, each with a unique decor that slots the viewer into a role within the piece. Sitting on a contemporary sofa and watching the video Roleplay, we are the confidantes of an American couple answering questions on camera about their marriage. We could be facing them across their coffee table; but we are also detached spectators, apathetically watching their life on a TV screen like any other domestic soap.

One room along, in Meditation on Disappointing Reading, we sit on traditional wooden stools as if at the dinner table of the daughter of Madam Liang, who is preparing a meal for the spirit of her departed mother. The action takes place in the present, but the furniture leaves the viewer feeling closer to the Republican era of the departed mother, conjuring up the out-of-body experience of “pan-shamans.”

The layout of the exhibition complements its contents. A long dark corridor stretches around the back of the exhibition space, leading the viewer to Obsessions. In the privacy and intimacy of this secret space, we can sit in a single armchair or lounge on a mattress laid on the floor. On screen, an architect imagines his own subconscious as a building to be explored—here represented as the hulking, ruined Fusuijing socialist building in central Beijing.

Wang’s characters are often swallowed by the dark, savage landscapes of their motherland. The Tetralogy slowly blows through frigid wildernesses far from the city, and down underground in sweaty subterranean raves. A ruined building becomes a den for a scholar’s suicidal thoughts; the 2018 murders-for-revenge committed by migrant worker Zhang Koukou are lost in a vast maize field; and Guo Qinguang is swamped by the endless umbrellas of lotus leaves in a traditional Chinese garden.

The result is an extra character present in every scene: one that’s vast, ominous, and all-powerful, beyond ordinary comprehension and control.

During the Spring Festival holiday of 2018, a migrant worker named Zhang Koukou murdered a neighbor and his two sons, vengeance for the neighbor having beaten Zhang’s mother to death 20 years before.

The case fascinated artist Wang Tuo. “What era is society staying in?” he asked at an interview held by UCCA Beijing. “We have an entire judicial system grafted from the West on the one hand...But at the same time, the hearts of ordinary people are still practicing a traditional Chinese system of benevolence, justice, and morality—that is, a traditional Confucian system.”

This question led him down a rabbit hole that led to The Northeast Tetralogy, following the threads of cause and consequence connecting small historical events to wider Chinese society. It continues his exploration of the parallels of traditional and modern Chinese culture, which has informed his work since he returned to China in 2017 after an extended stay in the US. His country suddenly felt like a vast unknowable mass, impossible to comprehend and powerless to resist.

Originally, you studied biology at university. Why not painting?

Wang Tuo: My father was a university art professor but he didn’t want me to be an artist. He taught me when I was a kid that if you’re a man, and smart, you don’t need to be an artist. I didn’t even think I could be one.

What made you change your mind?

After I got my Bachelor’s degree, I got a job in environmental science, which was quite boring. I just wanted to do something creative. Of course, I faced a lot of pressure and a lot of negativity. The only way out for me was to have a Master’s in art. Tsinghua University was the most difficult art course in China to get into, so these were my two darkest years, as changing my career was a big decision. Friends and family thought I was crazy to go for something with such great uncertainty, but I passed the exam successfully.

At Tsinghua, my education was purely done in the Socialist Realist style. My professor was even educated in St Petersburg! For a lot of my classmates, Tsinghua University is the pinnacle of their career because after they get their degree, they can go to any university outside of Beijing and get a good teaching job. But I was just a baby. I wanted to digest more, to go abroad and see something different. Out of my whole class, I was the only one who went abroad.

But when I was living in New York [after graduating from Boston University in 2014], I also felt slightly limited. The idea that when you’re in the West you can express yourself however you want isn’t actually true all the time. In New York, if you’re an artist from China you’re expected to talk about censorship or politics. I had a group show, and I made several pieces, and the protagonists were all white, but my friends and visiting curators said, “Why don’t you make the same story but just with Chinese people. If they’re Chinese, that’s right.” They wanted me to be a Chinese artist, and I tried to fight against that. I want to talk about something as an international artist.

Can you explain what pan-shamanism is?

I sort of invented that word. I moved back to China in 2017. My hometown is in Changchun, where we have a lot of religious happenings. The essence of it is derived from shamanism, which we call tiao dashen (跳大神).

I didn’t even know my great-grandmother was a shaman. This was around the 1940s, the 1950s. I never had a chance to talk to her and my family never mentioned it to me, as that’s not something that gives people pride. You don’t have a choice in becoming a shaman; it’s like fate. In a lot of cases, there is a crisis or tragedy that led to the change. Shamans make predictions, and sometimes they can connect up to the dead and the ancestors, like psychics in the West.

When I was a kid I saw a shaman ritual and I was frightened. The way they dance is quite savage, like they’re crazy or insane. They made loud noises, and a lot of the time you don’t know what they’re saying. This is because they’re trying to talk to other spirits, like animals, so at certain points they even become animals and make their noises. Also, they have to wear a lot of bells on a belt, and they shake these a lot. They wear a headdress that covers their face.

The government didn’t want to display the supernatural narrative, and just want the performance to be good and entertaining. State-funded “shamans” dress beautifully, and the sound they make is more like music, and [their movements] are like a dance. It’s gone from something formless, to something with form.

With pan-shamanism, everything could be shamanism. If you accidentally step into a nightclub, if you are watching a rock ’n’ roll concert, those could be all turned into something like a shaman ritual. The ritual itself doesn’t matter; it’s about what you believe in. Shamanism is like the medium, but history is the thing that I want to connect up to. Pan-shamanism is a particular experience for people to look at history, not just the time and space they are living in right now.

How do you connect China’s swift development with the idea of looking back into history?

When we look at a train, it’s moving forward. That’s because we’re standing at this point of time and space, but my point is if we could jump out of the point where we are right now, anything could be the past and anything could be a future. My piece is trying to connect speed to the switching of people’s identity. In the first work, Smoke and Fire, and the second work, Distorting Worlds, [Zhang Koukou] is a migrant worker in the city, but when he took his train, he moved really fast back to his home. When he was at his home he became something else, an assassin. Speed links his two different identities from the village and the city. It links up different places in China and also allows you to change your identity.

Where do you find inspiration?

I think the most important thing is to have a real life. Every time I get back to Beijing, that’s the time when I have this idea, “I’m an artist.” But when I’m in my hometown, when I’m with my parents, my family, and my childhood friends, my identity shifts. We don’t even have a concept of “art” in that part of China. If I said to a friend in Changchun “I’m an artist,” they wouldn’t think you’re an artist because you’re not making big paintings about the beautiful future we have. But I think this is a good thing: as nobody treats me as an artist, I never think about art in my hometown. There, you can touch the real texture of normal people’s lives. Just don’t confine yourself to the track of being “an artist.” That’s really fake. – A.C.

Wang Tuo (born in 1984 in Changchun, Jilin province) earned a Bachelor’s degree in biology from Northeast Normal University in 2007. He then attended Tsinghua University’s MA course in painting, graduating in 2012, and gained his MFA in Painting from Boston University in 2014. Previous exhibitors of his work include Queens Museum (New York, 2017); National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art (Seoul, 2020); the 13th Shanghai Biennale (2021); and WHITE SPACE (Beijing, 2020).

Wang Tuo’s Savage Country is a story from our issue, “Call of the Wild.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.