Could China take the gold in pot-tossing and horn-clashing?

China has had an impressive showing at the 2021 Olympic Games in Tokyo, getting off to an early lead in the medals table and staying at (or near) the top ever since. Today's Chinese athletes may be celebrated for their prowess in diving, table tennis, and weightlifting, but had they competed a few millennia ago, they might have excelled at completely different sports.

With thousands of years of history and many inventions to its name, China has been celebrated (sometimes dubiously) as the birthplace of various modern sports like football (cuju, 蹴鞠) and golf (chuiwan, 锤丸). Here are a few more sports from ancient China that might be due for a renaissance in the modern day:

Pitch Pot 投壶

Pitch-pot originated in the Spring and Autumn period (770 – 476 BCE), created as an alternative to archery, one of the “six essential arts” for a Confucian junzi (君子, gentleman) to master. During diplomatic banquets, hosts would invite guests to a polite arrow-shooting match. The guests could not decline the offer, as this would signal incompetence at a skill any respectable adult male was expected to have.

But what about people who couldn't shoot arrows for health reasons? There was "pitch pot (touhu, 投壶)," which required players to throw arrows or sticks into a canister from a distance. Those who got the most arrows into the canister won the game. Pitch pot became so popular that it was added into the rituals of diplomacy, as indicated in the history book The Commentary of Zuo (《左传》): “Duke Zhao of Jin invited Duke Jing of Qi to a banquet...and they played a game of pitch-pot." By the Qin dynasty (221 – 206 BCE), the game had become popular among scholar-officials at drinking parties, later a recreational pastime for literati and ordinary people, losing its ceremonial role.

Horn-Clashing 角抵

In Chinese legend, over 4,600 years ago, soldiers led by the god-king Chiyou (蚩尤) fought with the Yellow Emperor’s army. Chiyou's troops wore helmets with horns during the fighting, allegedly inspired by an ancient military art called juedi (角抵), which literally means "horn-clashing," similar to modern wrestling. It was first recorded under the name jueli (角力, horn power) in the Book of Rites (《礼记》) from the Western Zhou dynasty (1046 – 771 BCE), and was described as a military drill for soldiers, though they no longer wore the headgear by that time. It became known as juedi in the Qin dynasty, and transformed into a performance rather than an army exercise, as the Qin emperor feared rebellion from ordinary people and tried to restrict the learning of martial arts.

The rules of juedi were rather simple: Two wrestlers fight bare-handed, and whoever gets their rival to fall first wins the match. Archeologists excavated a painting on a wooden comb from the Qin dynasty in Hubei province in 1975 that showed two topless players wearing black belts, shorts, and curved slippers, lunging at each other with their arms outstretched. Another person, believed to be the judge, stands on their left side. Wrestling was in vogue during the Song dynasty (960 – 1279), with ordinary people traveling hundreds of li to watch juedi shows around the country. The court also hosted juedi matches to improve soldiers' skills. Yang Wanli (杨万里), a poet of the period, exclaimed in his "Juedi Poem (《角抵诗》)" after watching a court wrestling match: “There was an exciting wrestling match in the square, the emperor was watching the match in a high mood (广场妙戏斗程材,才得天颜一笑开).”

Wood Bowling 木射

Mushe (木射), also known as 15-pin bowling (十五柱球戏), was popular in the Tang dynasty (618 – 907). It resembles modern-day bowling. Players were expected to knock down pins from a distance by rolling a wooden ball. Lu Bing (陆秉) of the Tang dynasty once wrote a book called Mushe Painting (《木射图》) to explain the rules of the sport, but this volume was lost to history. In the Song dynasty, Chao Gongwu, a courtier who read the original book, summarized the rules in his own book Records of Books Read in My Studio in the Province (《郡斋读书志》): Fifteen bamboo shoot-shaped pins were set in a parallel row on the ground, each inscribed with characters related to a set of morals in an attempt to teach people ethics. There were ten pins inscribed in red with the characters 仁 (rén, kindness), 义 (yì, justice), 礼 (lǐ, etiquette), 智 ( zhì, wisdom), 信 (xìn, honesty), 温 (wēn, gentleness), 良 (liáng, goodness), 恭 (gōng, respect), 俭 (jiǎn, thrift), and 让 (ràng, modesty). The other five pins had black characters: 慢 (màn, pride), 傲 (ào, arrogance), 佞 (nìng, sycophancy), 贪 (tān, avarice), and 滥 (làn, abuse). Those who knocked down red-character pins would win, and those who knocked down black-character pins would lose.

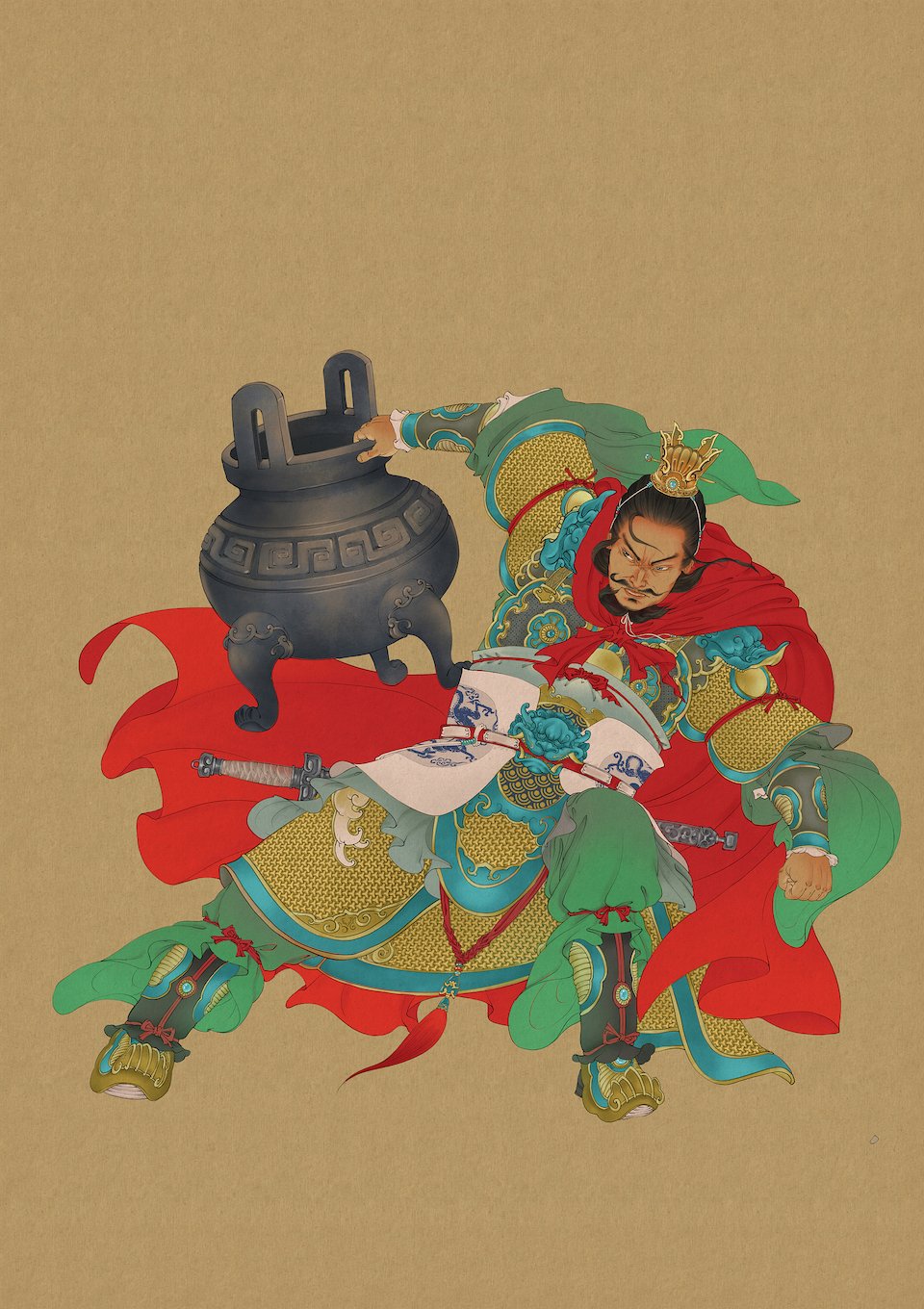

Vessel-Lifting 扛鼎

Chinese weightlifters were the heavily-favored at this Olympics, having won every competition they entered in the men's category and all but one (where they won silver) in the women's category. In ancient times, if you are able to stand steadily on your feet while holding up huge bronze ding (鼎) over your head, you will also be praised as a powerful man. The ding is an ancient cooking vessel usually made of bronze or clay, weighing hundreds of kilograms. It often doubled as exercise equipment for building up muscle strength in ancient China. In the Tang dynasty, army recruits were required to be able to lift a ding to enter military service.

The immense weight of the ding, however, made it dangerous to lift. During the fourth century BCE, the 23-year-old King Wu of the Qin state died after a ding-lifting competition. Based on historical records, he broke his shin and "blood poured from his eyes" (perhaps from a burst blood vessel). After the Tang dynasty, stone discs and stone padlocks emerged as alternative weightlifting equipment for ordinary people. The sport also gave rise to a four-character idiom (chengyu), “力能扛鼎” (lìnénggāngdǐng, so powerful as to be able to lift up a ding), which refers to people of great strength.