Stories and idioms about seven people who overcame challenging obstacles to read

Chinese people are reading less and less. According to a report released by the Chinese Academy of Press and Publication, Chinese adults read on average 4.7 printed books and 3.29 digital books in 2020—slightly up from the previous year, as the Covid-19 pandemic seems to have given a lot of people more time to read.

According to the report, only one-third of Chinese adults were satisfied with the amount of books they read in a year, and many said their long work hours and fast-paced lifestyle didn’t give them time to read. But let’s face it—that excuse wouldn’t have held water in ancient times. Looking back on history, there are many stories about book-lovers overcoming extraordinary obstacles to keep on reading and obtain an education, many of which were summarized into chengyu to inspire others to acquire more knowledge.

凿壁偷光 záobì tōuguāng

Bore a hole into the wall to steal light

In the Han dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE), there was a young man named Kuang Heng (匡衡). As a child, he loved reading very much, but his family was so poor that they couldn’t even afford to buy a candle. Kuang rued the fact that he couldn’t read at night, until one day, when he saw a candle shining in his neighbor’s house, he had an idea: making a small hole in the wall adjoining the two houses, and reading by the glimmer of light that shone through it. Though the light was weak, Kuang kept reading night after night, and finally grew up to become a famous scholar. His story was then recorded as this chengyu to describe the pursuit of knowledge under challenging conditions.

囊萤映雪 nángyíng yìngxuě

Reading by bagged fireflies and reflected light of snow

Kuang was not the only man to face difficulties reading due to poverty. Two men in the Jin dynasty (265 – 420), who also couldn’t afford to buy lamp oil or candles, managed to find other solutions to this problem.

The first man was named Che Yin (车胤). He came up with an idea on a summer’s night when he saw many fireflies hovering in the air. Che caught as many fireflies as he could, and put them all in a white silk bag. This he used as a lamp to read under. From then on, Che began to catch fireflies every night to use as lamps. After several years of reading and studying, he became a government official.

The other man was called Sun Kang (孙康). Unlike Che, he found his solution in winter. Though it got dark earlier in winter, Sun found that there was actually light reflected by the snow, so it was often brighter outside of the house than inside. Thereafter, he would often read in his yard at night regardless of the freezing weather, and he too became a successful government official.

The two stories were then put together, forming this chengyu, which is now used to refer to those who study hard in difficult conditions.

映月读书 yìngyuè dúshū

Reading by the moonlight

Maybe the stories of Kuang, Che, and Sun didn’t spread widely enough in ancient China, because Jiang Mi (江泌) of the Northern and Southern dynasties (420 – 589) clearly didn’t know their methods. When Jiang was young, he had to do odd jobs in the daytime in order to provide for his family, so he was only able to read at night. Unable to afford lamp oil as well, he read by the light of the moon. When the moon began to set, he would climb a ladder to the roof in an attempt to get more light. Sometimes, he was so sleepy that he toppled over, but he quickly regathered himself and continued reading, until he was finally able to become a scholar famous for being loyal and filial.

Like the previous two, Jiang’s story became a chengyu, usually describing people in poverty studying hard.

高凤流麦 Gāo Fèng liú mài

Gao Feng let the wheat be swept away

The Book of Later Han recorded a story about Gao Feng (高凤), a book-lover in the Han dynasty. When Gao was young, his family made a living by farming, but Gao spent most of his time reading. One day, his wife went to the fields, leaving Gao alone in their yard, where the wheat they had harvested was drying in the sun. Gao’s wife asked him to keep an eye on the chickens in case they ate the wheat.

A heavy storm came, but Gao was so concentrated on reading that he didn’t notice. When his wife came back, the wheat had already been swept away by the wind.

Gao later became a famous scholar. The history books recorded that even when he was very old, he was still always seen with a book in his hand. The chengyu inspired by his story is used to describe people fully absorbed by reading.

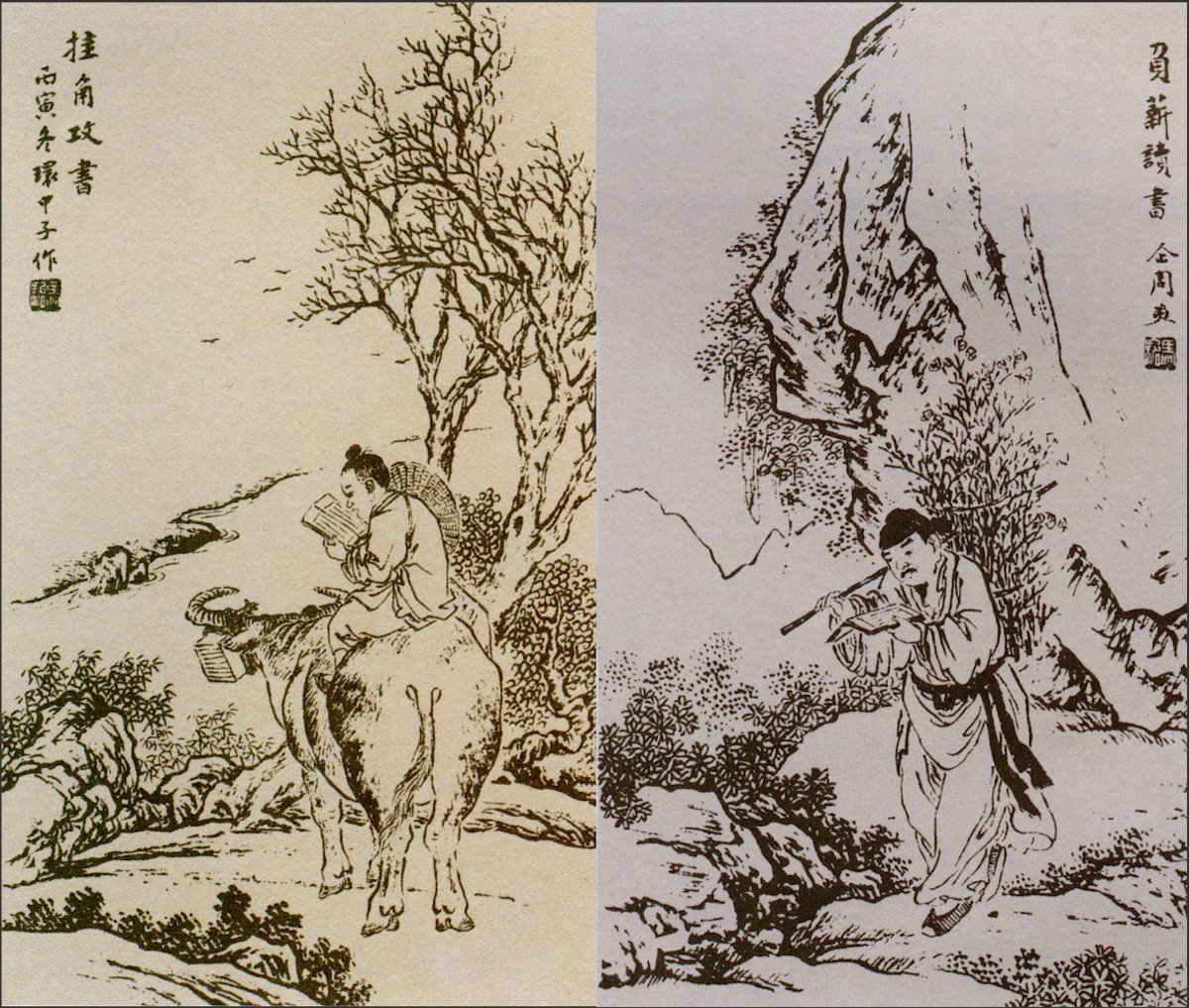

负薪挂角 fùxīn guàjiǎo

Reading while carrying firewood and hanging books on ox horns

This chengyu is also made up of two stories. One is about Zhu Maichen (朱买臣), a poor man from the Han dynasty. Already in his 40s, Zhu made a living by cutting and selling firewood with his wife.

However, he always read books while carrying firewood to the market, reciting the verses loudly along the way. People all laughed at Zhu, causing his wife great embarrassment. She tried to persuade him to stop reading, and when that didn’t work, she threatened to divorce him. Zhu, however, said that he would become successful in his 50s, and begged her to stay. His wife said she didn’t believe reading could lead Zhu to success, and eventually left him, but Zhu still read every day.

Years later, Zhu was recommended to become an official, and his ex-wife begged him to take her back. But Zhu turned her down. Zhu’s story is often titled as “Reading While Carrying Firewood (负薪读书).”

The second story is about Li Mi (李密) from the Sui dynasty (581 – 618). Li became a low-ranking official at the age of 15, but was soon dismissed, because the emperor felt Li was too young for such responsibility.

Li left the court and made a living herding cattle instead. Every day, he would hang a book on the horn of one of his oxen, and read sitting on the back of the beast. One day, Yang Su (杨素), a high-ranking official, observed Li reading while riding an ox, and predicted that Li would have a promising future.

Li later led a rebellion against the tyranny of the Sui government. Though he didn’t manage to overthrow the rule of Sui, his diligence was remembered. Li’s story was summarized as “Hanging Books on Ox Horns (牛角挂书),” which was combined with the title of Zhu’s story to form another chengyu (负薪挂角) about diligent study under difficult conditions.