A WeChat crackdown on student LGBT organizations raises the alarm about the future of sexual minority voices in China

The public WeChat accounts of over 20 LGBT+ organizations from universities and colleges across China were suspended without warning on the night of June 6. The closures affected a wide swath of institutions, from Nanjing University and the Huazhong University of Science and Technology in Wuhan, to Beijing’s prestigious Renmin, Tsinghua, and Peking Universities.

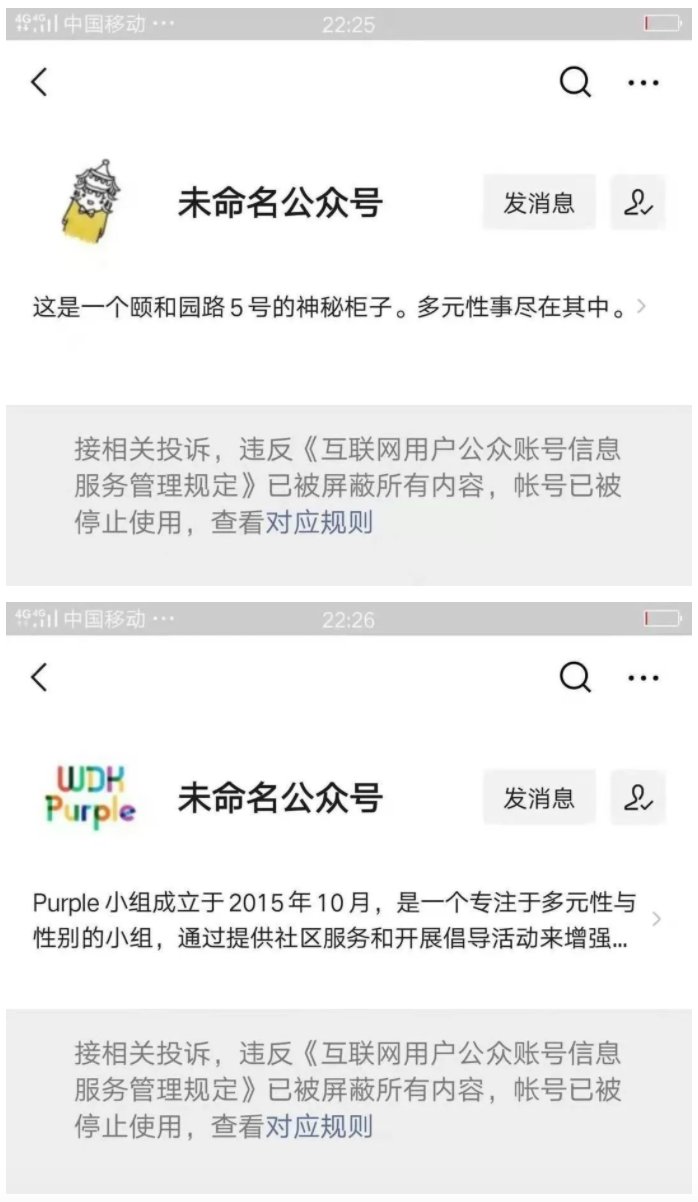

News of the shutdown appeared on microblogging platform Weibo shortly before 10 p.m. on Tuesday, with multiple student groups reporting that they were unable to access their accounts and finding past content on their accounts deleted. Groups’ account names were changed to “Unnamed Account.”

WeChat gave no advance warning and offered no clear reasons for the closure. On the home page of many of the now-deactivated accounts, a notice states that the account had received complaints and “all content has been blocked for violating the ‘Regulations on the Management of Internet User Public Account Information Services.’”

In January, LGBT groups had raised concerns around new rules from the Cyberspace Administration of China requiring self-publishers to obtain a license to publish about current affairs on social media. WeChat, China’s biggest social media platform, followed with the statement, “We suggest you stop publishing content relating to politics, economics, military, foreign relations, major breaking news events and others, if you don’t have related licenses.”

“Most of us feel very angry and depressed, but there isn’t much we can do so now we are just trying to communicate and connect with each other,” an organizer of a Chinese LGBT student group affected by the closure, who wished to remain anonymous, told TWOC.

Homosexuality was only de-criminalized in China in 1997, and the Chinese Psychiatric Association removed it from their list of mental disorders in 2001. In 2015, however, experts from academia and the media concluded at a United Nations Development Program roundtable discussion in Beijing that LGBT identities “are still vastly underrepresented or represented inaccurately or negatively in mainstream media,” which “perpetuate and legitimize widespread stigma against sexual and gender minorities.”

“Given that sexuality education is absent in most Chinese schools, queer student groups at schools serve as an important platform for them to share information and reach other queer peers,” says Cui Le, a PhD candidate at the University of Auckland’s Faculty of Education and Work, who researches the experience of gay academics at Chinese universities. These advocacy groups had built bridges, raised awareness of LGBT ideas and issues, as well as helping LGBT students to realize their identity and assisting members suffering from depression. For example, the WeChat account of the Colorsworld group from Peking University had posted articles detailing memes, events, and LGBT-related news from around the world, and offered anonymous counseling sessions through WeChat’s messaging function.

Apart from supporting LGBT students, campus organizations rallied against wider heteronormatic beliefs in Chinese universities and schools. In Huazhong University in April 2017, a banner labeled LGBT “a decadent Western idea” and urged such individuals “to stay far away from our campus.” “It gave rise to grassroots opposition to combat LGBT hate within the campus,” says a worker at a Chinese LGBT-community NGO, who wished to remain anonymous. “The campus environment is actually improving because there are so many LGBT groups working in these campuses.”

But the environment has been taking a slow downturn. On May 15, 2017, “we held a large and public event which might catch the attention of our university students,” says the anonymous organizer of the closed-down LGBT group account. “We tried to bring rainbow flags into campus but we encountered suppression, and some security people stopped us from giving them out. Whenever they saw the rainbow flags they would take them.”

A court in Jiangsu province ruled earlier this year that a university textbook’s description of homosexuality as “a psychological disorder” was just an “academic view,” and therefore not factually incorrect as the anonymous student plaintiff had claimed. The book was free to remain on shelves. June saw Shanghai Pride cancelled yet again after issuing a sudden statement last year that they would be postponing for a unknown period of time due to “safety concerns.” Weibo has also removed video content and hashtags related to LGBT issues in recent years (though walked back on some of those decisions after public outcry).

Compared to decisions at the local level, Tuesday’s closure of dozens of information hubs nationwide is much more serious. For Cui, that this closure included prestigious universities like Tsinghua and Peking University “may signal a more rigid official attitude towards queer issues in Chinese education.” At the time of writing, the only deactivated account not affiliated with a university belonged to an NGO that raised sexual education awareness on university campuses, “so this is mainly focusing on campus issues,” says the NGO worker.

There had even been direct warning signs to Tuesday night’s closures. “For the past three months, these LGBT student groups have been continuously censored offline,” says the NGO worker, who states that teachers in some universities had contacted organizers of LGBT student groups, telling them not to include the name of the university in their WeChat posts or account names.

“For student activists, losing their public accounts mean they can no longer reach out to their audiences,” continues the NGO worker. Although many of these organizations have Weibo accounts, they found a much larger following on WeChat: Tsinghua’s “WDK Purple” organization had 400 followers on Weibo before the closure, but had 20,000 followers on WeChat, allowing them to advertise events and communicate with a much wider community. “This will really affect their daily operations,” the NGO worker suggests.

Some of these accounts had accumulated large followings beyond their campuses. “These official accounts are at the forefront of advocacy in China, spreading discourses of anti-discrimination and anti-homophobia,” the NGO worker argues. At the time of closure, some had 20,000 members from across the country. “But last night they lost them.”

The closure “will reinforce the heteronormatic culture in Chinese universities and schools,” warns Cui. “Queer students can see that their identity and organization are not tolerated and supported by the authorities.” He warns that LGBT individuals may have to “conceal their sexual identity” and “self-censor their queer group activities.”

For now, the organizations are focused on damage control: In a statement, the Zhihe Society of Fudan University has called for anyone who has kept copies of their articles to come forward, and that their campus activities will continue despite the closure. The US-based NGO Chinese Rainbow Network (CRN), a community organization for sexual and gender minorities in the Chinese diaspora, reminded netizens in this “emergency situation” that it has a crisis intervention and a listening space on its support hotline. Colorsworld has resorted to provocative pictures on Weibo of their icon, gray and colorless. Many LGBT groups around the country changed their account names to “Unnamed Account” in solidarity.

“We will try to set up a new WeChat account in the future,” says the student organizer. “But for now we will rely more on Weibo.” On that platform, they report that their number of followers has more than doubled in the space of one day.