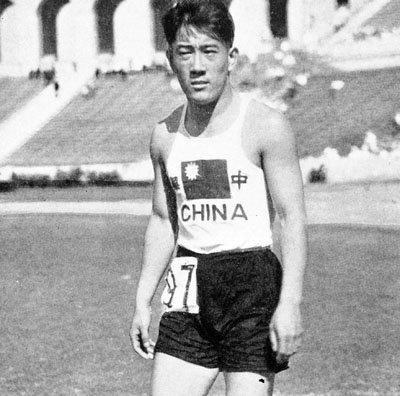

In 1932, Liu Changchun won no medals, but he did gain China recognition on the world stage

A year later than expected, the cauldron of the Tokyo Olympic Games was finally lit on Friday and the world's greatest athletes are already inspiring with their extraordinary feats. China's own competitors are off to a typically fast start, with the first gold of the Games going to Yang Qian in the women's 10-metre rifle event.

The country expects huge hauls of medals at every Games these days, but in the past even getting athletes into competition was a monumental achievement. In particular, the memory of Liu Changchun (刘长春) at the Los Angeles Summer Games 89 years ago, is an enduring reminder of how significant Olympic participation has been for China.

The runner did not win any medals (he didn’t even make the finals of his 100- and 200-meter events) but is celebrated as China’s first competitor at the Olympics. As the sole athlete from China to make it to the 1932 Games, Liu became a national hero not only for his historic achievement, but for the patriotism he displayed in the process.

Liu’s appearance at the Olympics was heavily influenced by the geopolitical situation at the time. Increasing aggression from Japan, including the invasion of China’s northeast and establishment of the puppet state of Manchukuo in early 1932, left the still fledgling Republic of China constantly fighting for international recognition.

It became increasingly clear to a growing number of Chinese officials that participation at the Olympics could be a vital source of recognition on the world stage and cement the Republic’s place in the community of nations.

“If a nation wants to pursue freedom and equality in today’s world where the weak serve as meat on which the strong can dine, they first must train strong and fit,” Wang Zhengting, Chinese Foreign Minister and President of the China National Amateur Athletic Federation (CNAAF), claimed in 1930.

Nevertheless, in May of 1932, with the LA Games due to start in just two months, the CNAAF announced they had no plans to send a team. But when Japanese authorities claimed they would send a team representing the new Manchukuo state, the Chinese were outraged, and officials forced to respond.

Japan announced it would send Liu Changchun, a talented runner from Liaoning province, as one of the Manchukuo athletes. Liu had been born to a poor family of fruit-pickers in Dalian. As a child, he allegedly ran five kilometers barefoot to school every day in order to preserve his shoes.

Later, Liu became a keen soccer player, and his athletic talent won him admission to Northeastern University in Shenyang, and become close to the university’s president, Zhang Xueliang (张学良). The son of warlord Zhang Zuolin (张作霖), who had been assassinated by the Japanese in 1928, Zhang was also effectively commander of China’s northeastern armies at a time.

On hearing the Japanese announcement that he and his university teammate Yu Xiwei would represent Manchukuo, Liu responded by telling the Tianjin newspaper L’impartial, “I am of the Chinese race, a descendant of the Yellow Emperor. I am Chinese, and will not represent the false Manchukuo at the Games of the Tenth Olympiad.” He denied the Japanese reports that he had agreed to their arrangement, stating, “My conscience is clear, my hot blood still flows; how could I forget China and become the puppet Manchukuo’s horse or cow?”

With China’s credibility on the line, Zhang Xueliang announced he would pay for Liu and Yu to go to the Olympics to represent the Republic. On July 8, Liu boarded a steamboat from Shanghai bound for America, but Yu appears to have been convinced or coerced by Japanese authorities in Manchuria not to attend—Liu would be the sole competitor for China.

Excitement at the prospect of a Chinese athlete competing on the world stage was mixed with dismay at the lowly status of Chinese sport in the press. An article in the Chinese periodical Sporting Weekly asked why Japan could send over 200 competitors, but China could barely manage one: “The education department says it is because of shortages of time and money. The CNAAF says there isn’t sufficient talent. These are not real reasons…The people devote everything we have to the nation, but the nation sure does not do anything to give we the people any hope at all.”

Liu’s three-week voyage across the ocean was not short on drama. On their first stop at Kobe, Japan, Liu and his coach were met with enthusiastic Japanese reporters who asked them how it felt to represent Manchukuo. “I declared strictly and firmly that the two of us represent the great Republic of China,” Liu’s coach recalled. A telegram from the Japanese Athletic Association also wished the “Manchukuo representatives” good luck.

At the Games, Liu was knocked out in the first qualifying round of both the 100- and 200-meter race, placing fifth and sixth—the weeks-long boat trip had no doubt impaired his performance. But his participation was significant nonetheless.

Officials noted that China’s participation at the games was a political success, if not a sporting one, in that it countered Japanese claims to the legitimacy of the state of Manchukuo. For a new nation struggling to impose itself on the world stage, the international sporting arena was an important platform, and Liu’s exploits fueled national pride at home.

“The [ROC national] flag of the white sun on the blue sky fluttered over the Coliseum, alongside the flags of the world’s nations for the first time. This has profound significance for our nation…On July 31, when Liu Changchun ran his 100-meter heat, the audience responded with a shockingly intense welcome, with applause that roared like thunder. The fact that our nation’s participation could leave the spectators with this kind of impression is very satisfying,” Sporting Weekly gushed.

After his athletic career, Liu became an important figure in sports governance while also working as a professor of physical education. He was a delegate of the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference in 1978, and served as vice chairman of the Chinese Olympic Committee after it was established in 1979. He died in 1983.

In 2008, as China prepared to host its first Olympics, a film of Liu’s appearance at the 1932 games was made. Liu’s humble background, patriotism, and defiance against the Japanese made for a compelling narrative of resistance and nationalism in the face of foreign threat.

In a 2003 speech in the US, Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao touched on Liu Changchun’s enduring significance, “Although he didn’t achieve anything exceptional [there], this single person who attended the Olympics affected the whole nation’s hearts.”