As China’s space program sets its sights on the Red Planet, a barren desert in Qinghai is becoming an oasis for simulated space travel

The scorching sands of the Mangnai Desert stretch as far as my eyes can see. An asphalt road runs like a lonely black strip through the sands, which is coarse with stones and salt strewn over the top like a thin layer of snow. A small road veers off into the desert—that is where I need to go.

If not for Baidu Maps, I would never have noticed this nondescript path. It is only made up of tire tracks from previous adventurers, lined with brown crystal formations that peek out of the bleached sand. I can smell the unique chemistry of this place and sense the alkaline air slowly spreading tiny crystals all over the road, tinting my dark backpack and sneakers whitish-yellow as I traverse. From this primitive intersection, I can see no buildings or other signs of life.

The day before I’d ridden my motorbike across the 4,500-meter high Dangjin Mountain Pass from Gansu province to the Tibetan plateau. The gas station employees at a crossroads just outside Lenghu (“Cold Lake”), an abandoned oil colony in the Qaidam Basin of western Qinghai province, told me that further down the road there’s a “Mars Camp” in the middle of the desert. It is said to be one of the few places on Earth that most closely resemble conditions on Mars—I had to check it out.

This is one of the remotest places in China, an area usually avoided by casual travelers and tourists. It is virtually uninhabited, and 250 kilometers from the nearest city of Dunhuang in Gansu province. But for China’s up-and-coming space tourism industry, these forbidding conditions are ideal. “We can get a whole group of up to 50 tourists who will stay here for several days,” says Yang Ruo, a caretaker at Lenghu Mars Camp, the space simulation base 50 meters south of the oil enclave, which offers a chance for civilians to experience life on a potential future space colony on the Red Planet.

Covering over 5 hectares of desert, Mars Camp comprises living quarters mostly constructed from discarded shipping containers made of steel. From above, the individual capsules where guests sleep look like a network of interlocking portable segments running along the sand to the education center at the entrance. On the hills above the camp, I can see a forest of rocks nicknamed the “City of Ghosts”—not only because of the howls the wind makes as it forces its way through the gaps between boulders, but also in memory of the travelers who never made it through this harsh terrain.

China’s western deserts are seeing a boom in space tourism, with space-experience and educational centers springing up in Qinghai, Gansu, and nearby Xinjiang. This coincides with an increase in the nation’s space activity—most recently with China’s Tianwen-1 mission, which landed a rover on Mars on May 14, 2021—in tandem with a surge of interest in Chinese science fiction.

With a price-tag of 150 million RMB (22.3 million USD), Lenghu’s Mars Camp was China’s first commercial space simulation base for the public, opening its doors in 2019 after one year of construction. Billed not only as a tourist site, but also as a place for scientific learning and “patriotic education,” the camp attracts a diverse group of public and private visitors—from “Young Pioneers” in primary school to government delegations—all making the pilgrimage to get as close to Mars as is currently possible.

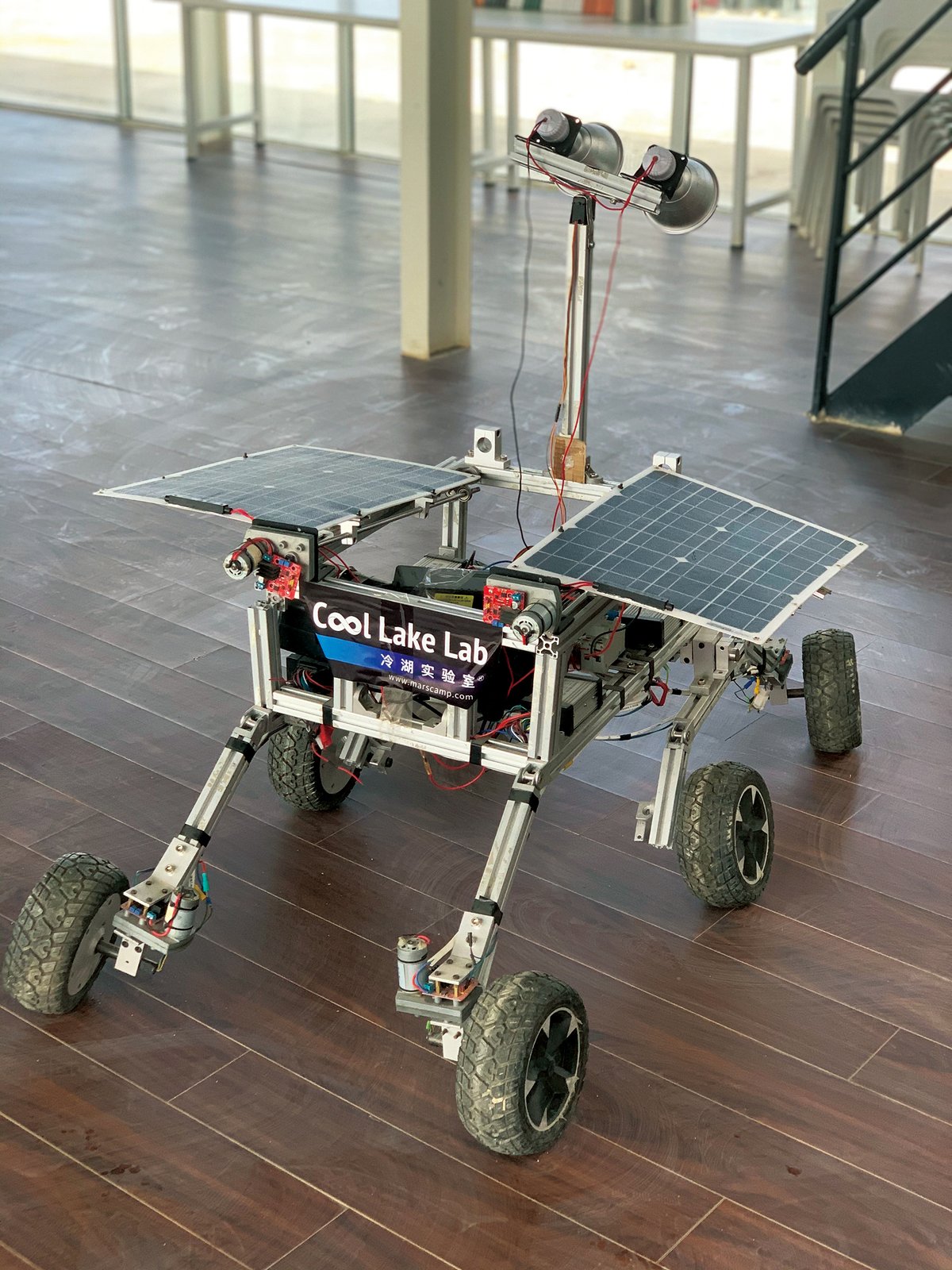

The base has living quarters for up to 60 people, equipped with various scientific instruments (which visitors can operate) that measure the desert’s weather conditions. It also has a gyroscope, a machine used in some space-training centers to simulate flying in zero-gravity. There is a dining hall for “students,” as Yang refers to the visitors. “This is also where we have group activities, like driving the robot Mars rover,” she says, pointing to a small six-wheeled vehicle on the floor. It is only about a meter tall, with two wings of solar panels protruding from each side.

Online figures for the cost of a stay at Mars Camp vary: 1,980 RMB for a two-day sampler, 3,600 RMB for a three-day “Mars Survival” simulation, and 19,800 RMB for a ten-day youth camp, which includes classes on astrobiology and engineering. Individual tent-camping fees run from 100 to 1,200 RMB per night. The camp is connected to a paved “Mars No. 1 Road” which branches off the equally lonely G315 Highway from the provincial capital at Xining, nearly 1,000 kilometers away. With little to no phone signal until one reaches the camp, and plenty of selfie opportunities in the middle of the empty road, any passing traveler can drive by for a taste of traversing an alien world.

The living conditions at Mars Camp are designed to mimic space travel. Campers dine on boiled vegetables and Spam, participate in a mock rescue mission on Mars, and wake up to an “alien invasion” siren to catch a gorgeous sunrise over the desert. They also take field trips to the oil colony, formerly one of China’s four major oil fields. From 1955 to 1977, until oil began to run out, some 25,000 workers lived at Lenghu and produced 300,000 barrels of crude annually. A small settlement of 200 people, run by PetroChina, is now all that’s left along with picturesque ruins: hollowed-out workers’ barracks, gates with bombastic slogans, even the shell of a bus.

Despite the Covid-19 pandemic’s chokehold on domestic tourism, the Chinese public has continued its interest in space, thanks to prominent state media coverage of space missions like the Mars landing. The precursor to the Chinese space program were rocket programs developed in the 1950s by the military at the missile test facility in Inner Mongolia, named after the city of Jiuquan in nearby Gansu province, now one of China’s most advanced rocket-launch platforms.

It was here that one of China’s most notable launches occurred in 1970, when The East is Red 1 satellite successfully went into orbit, quickly considered one of the nation’s greatest scientific achievements. During the Mao years, China’s most impressive scientific milestones were often summed up as “Two Bombs, One Satellite,” with the bombs referring to the country’s nuclear and ballistic missile programs. China launched its first manned space mission in 2003, when Yang Liwei became the first Chinese astronaut, or taikonaut (the English name for Chinese space voyagers, like Russian “cosmonauts”), to orbit the Earth in the Shenzhou-5.

Since then, China has upped its space game considerably, with a mission to the far side of the moon in 2019 by the Chang’e-4 probe, and the launch of a core module for a Chinese space station in May of 2021. A manned mission to Mars has been planned, but no launch date has been set so far.

Fascination with space is forging a whole new method for imagining the future of Chinese society—via science fiction. China’s modern science fiction following has increased substantially in the last 20 years. It was initially centered around the magazine Science Fiction World, which was estimated to have about 2 million readers in 1999. By 2016, the Global Times estimated a sci-fi readership of around 80 million among the general public. “Because sci-fi is aimed at the future, it eases people’s frustrations about the future,” science fiction writer Regina Wang Kanyu tells me after my visit to Mars Camp. “You can ask questions like what kind of future should we avert or pursue.”

In 2019, Wang attended an annual retreat the camp hosted for budding sci-fi writers, spending days living in the desert sands. Born in 1990, Wang is a member of a new generation of Chinese sci-fi writers who are publishing stories after older writers, like Liu Cixin, put the Chinese genre on the international map with Hugo Prize-winning works like the Three Body trilogy.

According to Wang, the popularity of sci-fi and Liu has led some local governments to invest in space-related tourist projects, believing it a good way to boost cultural development. There are now two other Mars camps in Jinchang, Gansu, and in the Hami Basin in Xinjiang. “[Local governments] look at works like Three-Body Problem and then they want to capitalize on it,” says Wang. There are some “ridiculous” places, she adds with a laugh, “like the crayfish sci-fi village in Hubei. They invite sci-fi writers to write a story about the village for PR, so there’s clearly a money side to it.”

Writers who come on the Mars Camp’s retreat may use the surroundings as inspiration in their stories. “We did star-gazing in a dark place and saw the gorgeous Milky Way. We also played space-survival games—everyone gets an occupation through a lottery and has to persuade the others that they deserve to live and go to space,” Wang recalls. There were science lectures, a visit to the Lenghu ruins, and a 10-kilometer hike and treasure hunt in the desert. “There was also a student summer camp when I was there, so we played with the kids, listened to their presentations, and watched their Mars vehicle competition.”

Wang says her time in the desert made a lasting impression on her. “Those scenes are buried in my mind and hopefully they will turn into stories in the future.” Mars Camp also holds a sci-fi contest where authors have to write stories about the oil colony ruins, with a chance to win several thousand RMB as a prize and have their work judged by luminaries like Liu Cixin and Wang Jinkang. Author Wang Nuonuo’s winning entry of 2018, the contest’s first year, described a former oil colony resident’s encounter with time-traveling Martians coming to revitalize the ruins in 2022.

Regina Wang’s own work often wrestles with society’s understandings of the technological developments it is living through: the integration of human and machine, and the unintended consequences of technology designed to make human lives better. In a recent story, “The Language Sheath,” she explores the pros and cons of language translation devices—which help humans demolish language barriers, but would also destroy other meanings in the flow of communication.

China has not begun any new space tourism projects this year, as the tourism industry continues to recover from the pandemic. But with an ever-increasing interest in both sci-fi and Chinese space exploration, the prospects for Mars Camp are promising.

With more intensive space exploration on the scientific agenda, there will also be plenty of future conundrums for China’s sci-fi writers to unravel. “There is such rapid technological change here in China and so much we don’t know [about new technology],” says Wang. “The rapid change has created a lot of anxieties. People are interested in looking for something that captures and reflects that change.”

Against the odds, Mars Camp still survives in the hostile sands of Qinghai, ready to take in yet another batch of wannabe-taikonauts.

Cover image by VCG

This is a story from our issue, “Something Old, Something New.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine. Alternatively, you can purchase the digital version from the iTunes Store.