Too many of the Chinese diaspora’s leading female artists and performers have been forgotten. Director Luka Yuanyuan Yang wants to reclaim their transnational legacies.

In 2018, I received a scholarship for a six-month residency in the United States. My research project focused on the history of Chinese performances in America, from Chinese opera and film to Chinatown nightclubs. Of all the books, papers, and documentaries I read or watched during those six months, one stood out above all the others: “Golden Gate Silver Light,” a 2013 documentary about the San Francisco-born Chinese director Esther Eng.

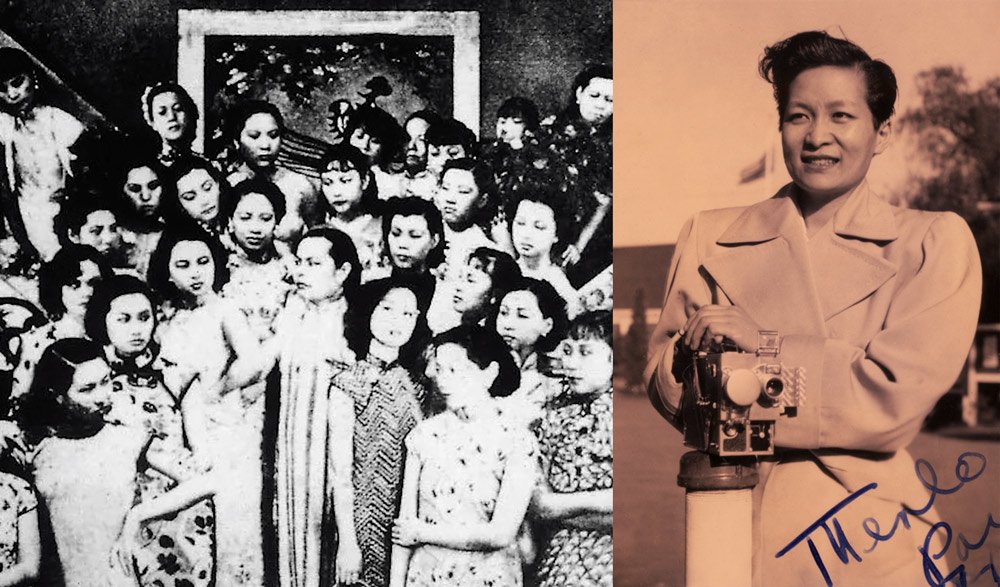

By the time “Golden Gate Silver Light” came out, Eng had been largely forgotten for decades. Her legacy might have vanished forever, if not for the 2009 discovery of more than 600 photos and film stills at a garbage collection site near the San Francisco Airport. Anti-Asian racism was everywhere in early 20th century Hollywood: Even outstanding performers like Anna May Wong were typecast as stereotypical “Orientals.” Eng, 10 years younger than Wong, was all too familiar with this state of affairs, but she refused to be silenced. In 1939, after a few years spent honing her craft in Hong Kong and just before returning to the United States, she directed the world’s first all-Chinese, all-female-cast film: “It’s a Women’s World.”

The film, which proclaimed that “modern independent women should not be attached to men,” has, like so many classic works produced by the Chinese diaspora, been lost. My heart ached as I flipped through the photos and film stills that did survive: How is it that such a talented, legendary figure could have been forgotten? And how many more Chinese diaspora women never got the mainstream recognition they deserved?

To try to answer these questions, I set out to gain a deeper understanding of Eng and other Chinese filmmakers, singers, and performing artists like her.

In San Francisco, my quest led me to 73-year-old Cynthia Yee. A jack-of-all-trades, she’s been a nightclub dancer, a jewelry shop owner, a magician, a beauty pageant winner, and a tour guide specializing in the haunted history of the city’s Chinatown. After her retirement in 2003, she founded the dance troupe Grant Avenue Follies. The majority of the troupe’s members are single women in their twilight years, brought together by their shared passion for dancing.

When I met her, one of Cynthia’s friends—and the group’s star performer—was Coby Yee (no relation). A former dancer and onetime owner of the iconic Forbidden City nightclub in the 1960s, Coby witnessed the golden age of San Francisco Chinatown’s nightclub scene. A second-generation immigrant, she never set out to become a burlesque dancer, yet it was only after she retired 20 years ago that she was finally able to follow her heart on the dance floor instead of performing solely to please a mostly white audience.

Coby’s story, like Cynthia’s, is inspiring and bitter all at once: Inspiring, in that after decades of frustration, they both held on to their optimism and insistence on living life to the fullest; bitter, because for all their talent, their accomplishments have rarely been recognized, much less remembered. Once hailed by newspapers as a “daring Chinese dancing doll,” Coby participated in multiple film shoots in Chinatown. Yet each time, her character wound up on the cutting room floor.

My new film, which I titled Women’s World in a tribute to Eng, was driven by the desire to document the lives of these Chinese female entertainers. Self- and crowd-funded, and conceived as a musical road trip, we invited members of Grant Avenue Follies—including Cynthia and Coby—on an international tour across locations of significance to both themselves and the history of Chinese American audiovisual culture more broadly: from San Francisco, Las Vegas, and Hawaii to Havana, Shanghai, and Beijing.

As the journey unfolded, I couldn’t help but reflect on the challenges these women had overcome. To be part of the Chinese diaspora in the 20th century was to confront not only racism and Sinophobia, but also the question of assimilation—all while being at the mercy of wild geopolitical swings. In Cuba, we visited Havana’s vanishing Chinatown and gave a performance at a Chinese theater-turned-martial arts school where Chinese filmmakers used to screen their films back in the 1950s. Back in China, Coby danced on the Bund in Shanghai and spoke through tears about her father’s never-realized dream of one day returning home with his family.

“The past is not dead, for it has never passed.” This phrase, a paraphrase of the famous William Faulkner line, was brought up by one of our interviewees in the United States, and it has echoed in my mind ever since. Even today, many Chinese in the US can still relate to Esther, Coby, and Cynthia’s stories. One of our producers, Louie Wang-Holborn, a Chinese woman who moved to the US 10 years ago, has talked about how much of herself she sees in these Asian American entertainers—and how imperative it is to reclaim and retell their stories at a time of rising prejudice against Asians and Chinese. And we’ve been astounded by the enthusiasm for the project among our backers so far. Especially in our current geopolitical moment, these woman’s lives stand testament to a century of shared dialogue, struggle, and perseverance that crosses national, generational, or cultural borders.

Sadly, our trip would be Coby’s last time in China. On Aug. 14, 2020, she passed away at the age of 93. She never stopped dancing, though: Her last performance came just one week before her death.

This story was originally published on Sixth Tone and has been republished with permission as part of our collaboration with Sixth Tone X, a platform featuring stories from respected Chinese media outlets.