Some anti-marriage activists are trying to lay claim to the self-comb legacy. They’re missing these women’s real significance.

This story was originally published on Sixth Tone and has been republished with permission as part of our collaboration with Sixth Tone X, a platform featuring stories from respected Chinese media outlets.

In my mother’s memories, my great-great-aunt was a stoic, formidable woman of 5-foot-2. The eldest child of an impoverished south China family in the 1890s, all five of her siblings died in childhood. She and her cousin—my great-grandfather—supported each other after their parents died, taking turns working and putting each other through school. Although she never married or had children of her own, after moving in with my great-grandfather and his family, she became the family matriarch, ruling over the household and all her nieces and nephews.

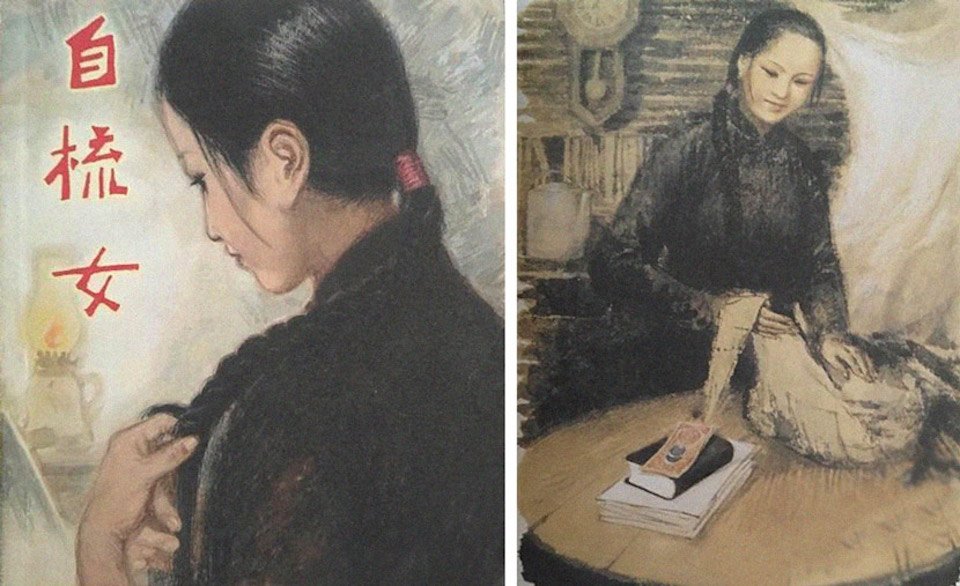

In my hometown of Panyu—once a fishing town, now an affluent district of the southern city of Guangzhou—people like my great-great-aunt used to be known as “self-comb women.” Traditionally, when women got married, they would ceremonially comb their hair into a bun, signifying they were no longer a maiden. Eventually, a mirror ritual evolved for women who opted out of marriage: A self-comb woman would shuqi, or brush her hair up, and perform other rituals associated with matrimony, such as worshipping at an ancestral shrine, gifting sweets to a younger brother, and hosting a celebratory feast. Only, instead of swearing her life to a man, she swore it to herself.

Young women in south China chose to self-comb for a variety of reasons. Some did so out of personal preference, unwilling to submit to the restrictions of married life. Others were pressured by their families, often because older sisters were traditionally expected to marry or self-comb before a younger brother could be wedded.

But for many more, it was primarily an economic decision. The 19th century saw the emergence of a booming silk industry around the Pearl River Delta, and nimble hands were required to harvest silkworm cocoons—or later, to operate new spinning machines. This created financial incentives for families to retain their daughters rather than marry them off.

Even after the decline of the silk industry, many self-comb women were able to find jobs as domestic helpers in colonial entrepôts like Hong Kong and Singapore, where their wages soon outstripped what their relations made farming.

Self-comb women enjoyed a unique status in an otherwise deeply patriarchal society. Breadwinners who remained attached to their natal families, self-comb women were accorded a degree of respect many married women were not. In an interview with Ye Ziling, a scholar who has studied the self-comb phenomenon, a self-comb woman from the southern city of Nanhai compared her self-combed aunts favorably to her mother: “They were respected…Unlike my mother, who never received any recognition in my family.”

Yet despite their anomalous position, self-comb women remained deeply enmeshed in China’s prevailing patriarchal social and family structures. Ye describes them as “dutiful daughters” who performed the key Confucian value of filial piety by working hard to provide for their families.

Many self-comb women financially took care of their siblings’ children, funding their educations or helping them build houses and start families of their own. In return, their nephews and nieces were expected to care for them in their old age. Even their decision to self-comb was conditioned by the need to be seen as “chaste” and thereby preserve their good name for their family and clan.

So it might seem odd that the self-comb women archetype would be unearthed and reframed as a proto-feminist act of protest. This May, domestic media outlet Pear Video interviewed 90-year-old Huang Ruiyun, the last living self-comb woman in the southern city of Shunde. When the resulting clip was posted to the outlet’s social media account under the headline “Life without Marriage, in Pursuit of Freedom,” the comments were flooded by users expressing their admiration for Huang and her self-comb peers—while some took the chance to make pointed remarks about continued societal pressure for women to marry.

“Even women 100 years ago were more clear-headed than today’s princess brides,” read one comment. Others went further, favorably comparing self-comb women to what they call “married donkeys”—a demeaning term for married women. “Donkeys sell (themselves) cheaply,” one wrote. “Marriage and relationships have completely brainwashed women,” added another.

A vocal anti-marriage faction emerged on the Chinese internet around 2015. Viewing marriage as an inherently exploitative institution and the primary instrument of oppression wielded by a patriarchal state only interested in women for their reproductive abilities, they called for a boycott. More recently, “married donkey” has become a favorite insult among this group, who use it to highlight married women’s supposed state of perpetual servitude while branding them as complicit in their own oppression. In 2017, over 73% of all divorce suits were filed by women. The next year, the marriage rate fell to a five-year low, according to official statistics.

Part of the problem is that women in contemporary China are still expected to bear the lion’s share of housework and take responsibility for child care. The nonparticipation of men in household chores is summed up by the buzzword “widow-style marriage,” even as a string of high-profile domestic abuse and intimate partner violence cases have sparked much deeper fears.

In rejecting marriage, it’s no surprise that Chinese women would look to earlier examples of “resistance” for inspiration. “Chinese women today need to learn from the self-comb women of Guangdong,” wrote one netizen in response to a report about a woman who was murdered by her husband this July. “It’s the only way.”

Thirty years ago, scholars like Hu Jie were arguing that self-comb women were victims of patriarchy who had either developed an irrational fear of marriage or who were forced to sacrifice individual happiness to support their families. Now their stories are undergoing a feminist reimagining, and a practice once denounced as patriarchal has become evidence of a long tradition of women writing their own destinies.

Reality, of course, is more nuanced. The decision to self-comb was often motivated by economic hardship and family responsibilities, and it always involved a negotiation with the same patriarchal social norms surrounding marriage, childbearing, labor, and filial duty—issues many Chinese women still struggle with today.

This does not mean that self-comb women have nothing to teach us. Far from it. There’s plenty of inspiration to be found in self-comb women without turning their lives into neat tales of personal liberation. Reducing self-comb women’s complex experiences into a simplistic anti-marriage framework, or using them to criticize or even insult married women, misinterprets their significance and does a disservice to their lives and the history of women more generally. Just to name one example, self-comb women belong to an oft-overlooked but ongoing tradition of immigrant women working as domestic help outside the Chinese mainland in places like Singapore and Hong Kong, where they provided the vital care work that kept the gears of these two metropolises grinding.

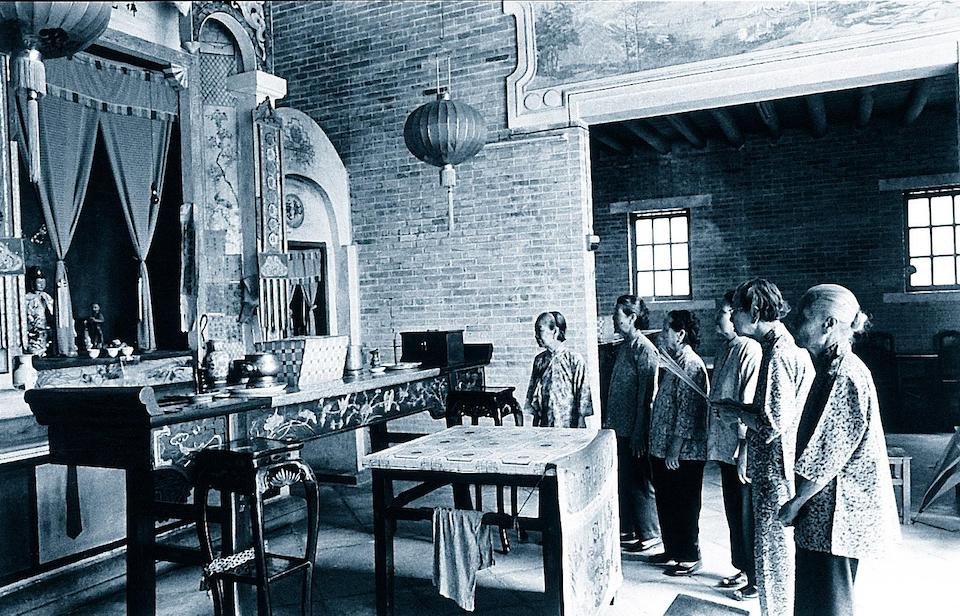

This October, my mother and I visited Shunde. Near evening, she proposed that we stop by the House of Ice and Jade, a distinctly Cantonese complex built in 1951 with funds pooled by the city’s self-comb women so they would always have a place to live. Standing in its dove-gray halls, I reflected on the women who came before me: my great-great aunt, her life marked by poverty and war; my grandmother, whose own life was upended by the Cultural Revolution; and my mother, who emigrated from China to Canada at the age of 35 and raised a child alone.

It’s easy to lionize those who fought against oppressive systems, treating their every victory as containing lessons we can use in our own battles today. But sometimes we can learn more from their everyday struggles, their compromises, and their persistence.

Editors: Cai Yiwen and Kilian O’Donnell; portrait artist: Zhang Zeqin.

Cover image by An Ge/FOTOE, Images from VCG, FOTOE, KongFZ