Cantonese swear by their wine-soaked meats with “clay pot rice”

“My parents sent me a whole lamb,” a Shanghai resident surnamed Peng boasted to news site K News in February, displaying the well-marbled gift her family mailed her from Shandong province ahead of Chinese New Year. With millions of Chinese choosing not to return home due to a sudden surge of new Covid-19 cases, packages of homemade food became an essential cure for homesickness during the family holiday.

For sending food to loved ones far away, preserved meat and sausages—腊肉 (làròu) and 腊肠 (làcháng)—are ideal choices due to their durability and cultural associations with the season. Their Chinese names refer to the fact they were traditionally cured, smoked, and air-dried or sun-dried in the 12th lunar month, 腊月 (làyuè). Although these foods are now available throughout the year, many keep up the tradition of home-curing meat in the winter.

Meat-preservation in China dates back to at least the Spring and Autumn period (770 – 476 BCE), when Confucius collected cured meat from his students as tuition fee. “I’ve never turned away a disciple who gives me ten pieces of dried meat,” the master commented in the Analects.

Sausages were first recorded in Qimin Yaoshu (《齐民要术》), an agricultural handbook from the Northern Wei dynasty (386 – 534). The recipe called for filling sheep intestines with a mix of finely chopped mutton, leek stems, and various seasonings. Sausages are basically made in the same way today, though pork and pig intestines are more common, and each region of China swears by its own version with local fillings and seasonings.

The provinces of Guangdong, Hunan, and Sichuan are renowned for lachang. Among these, the Cantonese style from Guangdong, known locally as lap cheong, has the most distinctive look and taste. Unlike the spicy and smoked Sichuan and Hunan versions, the ruby-red lap cheong has a sweet flavor and wine aroma, as it is seasoned with sugar and rice wine. It is often sold in Chinatowns abroad due to the global Cantonese diaspora.

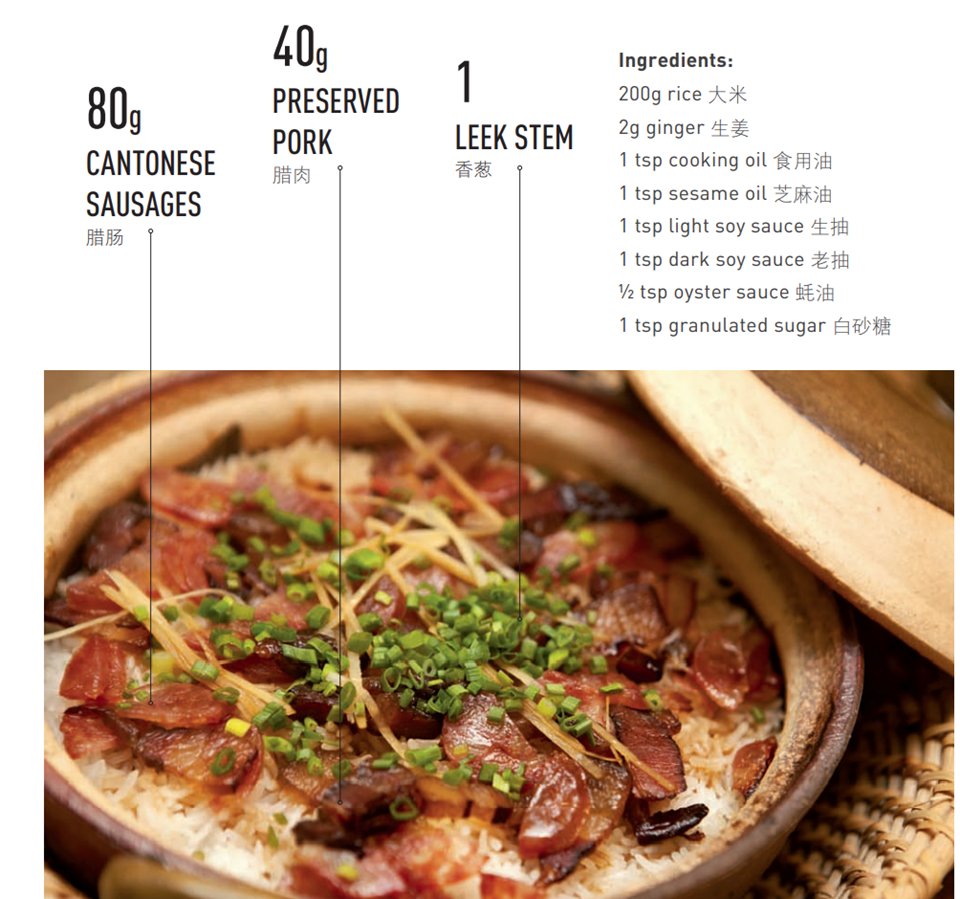

While people from other provinces commonly stir-fry the la sausages with vegetables, or consume them directly after steaming, lap cheong is typically eaten in one dish, “clay pot rice (煲仔饭).” The Cantonese word boujai (煲仔, “little pot”) refers to a heated clay pot that the dish is both cooked and served in.

Restaurants specializing in clay pot rice can be found on many street corners and in shopping malls in Guangdong and Hong Kong. Other ingredients may be added, such as beef, chicken, mushrooms, vegetables, or eggs. It is essential to cook the rice until it forms a crispy crust at the bottom, while the meat juice soaks the rice on top and makes a sizzling sound. The classic version calls for preserved pork and sausages, and can be made at home using a clay pot or rice cooker.

Steps:

- Wash the rice, soak it with water for half an hour, and drain it

- Wash the preserved pork and sausages. Cook them in water until the water boils, and cut them into thin slices

- Wash and chop the ginger and leek

- Brush the bottom of a clay pot with cooking oil. Add rice, and fill the pot with water about 1 cm above the rice

- Cook the rice over high heat until the water boils. Turn to low heat, and cook for 10 minutes

- Add the slices of pork, sausage, and ginger, and cook for another 10 minutes

- Mix the sesame oil, soy sauce, oyster sauce, and sugar with 2 tsp of water

- Sprinkle chopped leek stem and drizzle the sauce over the sizzling dish. Mix with the rice, and serve

Sausage Fest is a story from our issue, “Dawn of the Debt.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.