Diplomatic translation is never easy, but the task is all the more challenging when established protocols begin to fray

When diplomats from China and the United States met in Alaska for the first high-level bilateral talks of the Biden administration, few expected the translators to steal the spotlight. In China, Zhang Jing won praise for her calm and fluent translation of the Chinese representatives’ remarks, while Zhang’s American counterpart was criticized for amplifying the U.S. delegation’s already strident language.

The famous Chinese comparativist writer Qian Zhongshu once cited an Italian proverb to describe the work of a translator: traduttore traditore—“translator, traitor.” And it’s true: The wording chosen by a translator is always more or less “traitorous” to the original, but Qian wasn’t entirely fair in his assessment. Many linguistic betrayals are often the result of a translator’s loyalty, if not to the language used, then to established diplomatic protocols and speech. Take Zhang, for example. Tasked with translating a catchphrase used by one of the Chinese representatives—“We Chinese Aren’t Buying It!”—she chose to paraphrase, translating it as “This is not the way to deal with the Chinese people.” These adjustments become exponentially more fraught, however, in times of geopolitical upheaval.

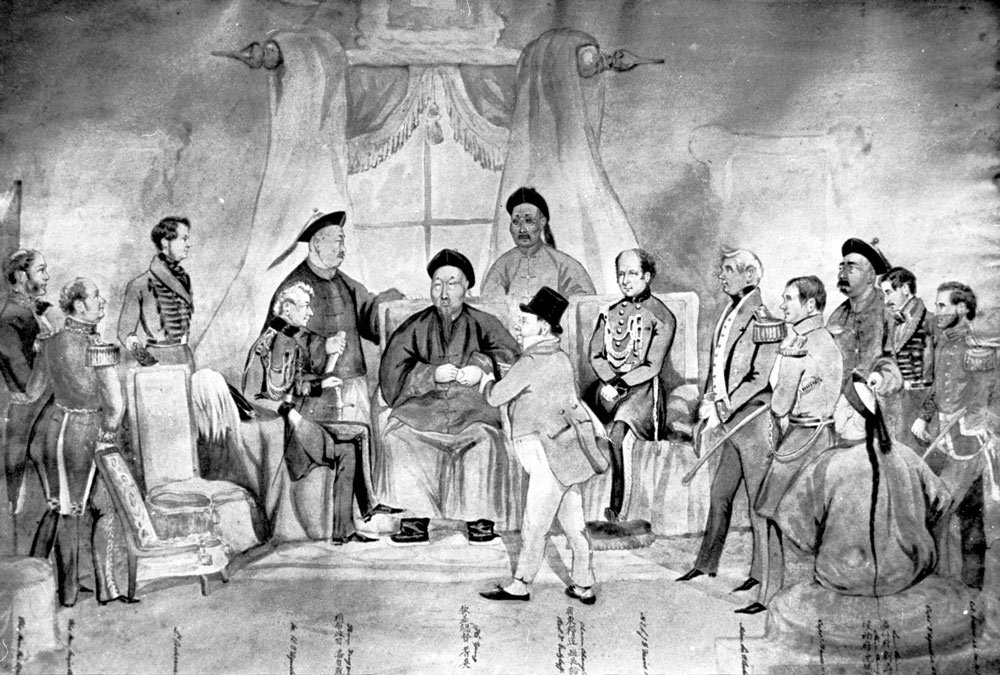

Looking back at the history of Sino-international diplomatic relations, there’s a long tradition of “loyal betrayals.” For example, the famous Macartney Mission to China in 1793 was defined by the supposedly arrogant reply of the Qianlong Emperor to King George III’s entreaties to establish formal diplomatic relations. The resulting diplomatic snafu is frequently cited as evidence of the Qing dynasty’s self-imposed isolation. But Lawrence Wang-Chi Wong, a professor at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, has argued that how Qianlong replied may have boiled down to decisions made, not by any diplomat, but by the man who translated King George III’s letter of state: likely José Bernardo de Almeida, a Jesuit priest living in Beijing.

In translation, the British crown’s attempt to establish equal diplomatic relations with China became a humble request to become a tributary of the Qing court. The original letter describes diplomat George Macartney’s purpose in conducting the mission according to European convention: “We have the happiness of being at peace with all the world, no time can be as propitious for extending the bounds of friendship and benevolence, and for proposing to communicate and receive those benefits which must result from an unreserved and amicable intercourse, between such great and civilized nations as China and Great Britain.”

The Chinese version reads differently: “Now that our country is at peace with all places, we must take advantage of this time to pay tribute to the Great Emperor of China, in the hope of gaining some benefit.”

At the end of the original letter, King George III makes his expectations of the relationship clear. “And it will give us the utmost satisfaction to learn that our wishes in that respect have been amply complied with and that we are brethren in sovereignty, so may a brotherly affection ever subsist between us,” it reads. The translation is far more toadying: “The envoys have been instructed in detail to be careful and respectful before the Great Emperor, and to appear sincere, and to be liked by the Great Emperor, for that is my heart’s desire.”

The translator’s reasons for “betraying” the original wording are understandable. He was uncertain about the possible consequences of a completely truthful translation—especially for himself, a foreign missionary who was already walking on thin ice in the Qing capital. For him, it was safer to follow the established protocols of Chinese tributary diplomacy in his translation, even if it meant “betraying” the language of the original letter.

A similar kind of “loyal betrayal” also occurred during the first formal diplomatic encounter between China and the United States. In 1844, half a century after the Macartney Mission, the US sent its own first mission to China. Like the Macartney Mission, the Cushing Mission presented the ruling Daoguang Emperor a personal letter from then-US President John Tyler. In his new book, not yet translated into English, University of Delaware professor Wang Yuanchong provides a fascinating analysis of how the letter was altered before being delivered. Wang argues that Keying, one of China’s de facto top diplomats, modified the translation of Tyler’s letter in ways that “made this state document look very much like a tableau of a tributary state that admired Chinese civilization and affluence.”

Take for example a paragraph describing the geographical locations of China and the US: “The rising sun looks upon the great mountains and great rivers of China. When he sets, he looks upon rivers and mountains equally large in the United States.” The original wording emphasizes that China and the U.S. are located in eastern and western hemispheres, and there is no superior or inferior. But in the Chinese translation, China’s “great mountains and great rivers” are rendered as “imperial lands,” while America’s “rivers and mountains equally large” are translated as “humble places”—making inequality between China and America immediately apparent. At other points, Keying softens Tyler’s phrasing: “We doubt not that you will be pleased that our messenger of peace, with this letter in his hand, shall come to Pekin (Beijing), and there deliver it” becomes, in Chinese translation, “I am sending an envoy to Pekin to present a letter to you, with the intention of peace, and I hope that the Great Emperor will not be displeased by it.” The effect is to make diplomat Caleb Cushing look more like a tributary’s envoy than a representative of an equal nation.

Concerning accuracy, Keying’s adjustments were undoubtedly a “betrayal,” even if they were loyal to the established diplomatic system of the Qing dynasty. It is not surprising that after reading President Tyler’s letter, the Daoguang Emperor’s only reply was the word “read.”

Since the late Qing, China’s interactions with the West have become more frequent, but the instinct, conscious or otherwise, toward “translation as betrayal” has not diminished. Interestingly, however, as speakers gained exposure to Western culture and languages, they were sometimes able to detect the “betrayals” of their translators. In August 1946, near the start of the civil war between the Communists and the Kuomintang government, the American journalist Anna Louise Strong sat down with Mao Zedong in the Communist stronghold of Yan’an. When she asked Mao what his views were on the possible use of the atomic bomb by the Kuomintang’s American allies, Mao was dismissive. “The atomic bomb is a paper tiger used by the American reactionaries to scare people; it looks scary, but in reality, it is not,” he replied.

Searching for an idiomatic translation of zhi laohu, or “paper tiger,” Mao’s elite school-educated and English-savvy minister of propaganda, Lu Dingyi, landed on the more familiar American word “scarecrow.” It was a term Strong would know, but it weakened the more profound criticism of Mao’s original statement.

Only Strong’s lack of reaction alerted Mao that something had been lost in translation, and he made a point of stopping the conversation to ask her if she had really understood what he meant.

Strong ventured it was something put in a rice paddy to scare birds away.

“No,” Mao said, switching to heavily accented English. “It is a paper tiger.”

Translated by Matt Turner

This story was originally published on Sixth Tone and has been republished with permission as part of our collaboration with Sixth Tone X, a platform featuring stories from respected Chinese media outlets.