A discussion with Chinese-Malaysian filmmaker Lau Kek Huat on identity and truths in documentaries

When Lau Kek Huat ticked the “filmmaking” box as his field of studies at National Taiwan University of Arts, it was the first time he realized that filmmaking was something one could “learn.”

He had come to Taiwan merely seeking a different kind of life. Before that, he had already completed a degree in business administration in Singapore, got hit by the 1997 financial crisis, and taught in a Chinese elementary school for four years. This was already a few steps removed from his original plan to work in a factory, like many other Chinese Malaysian kids did after high school in his hometown of Johor Bahru.

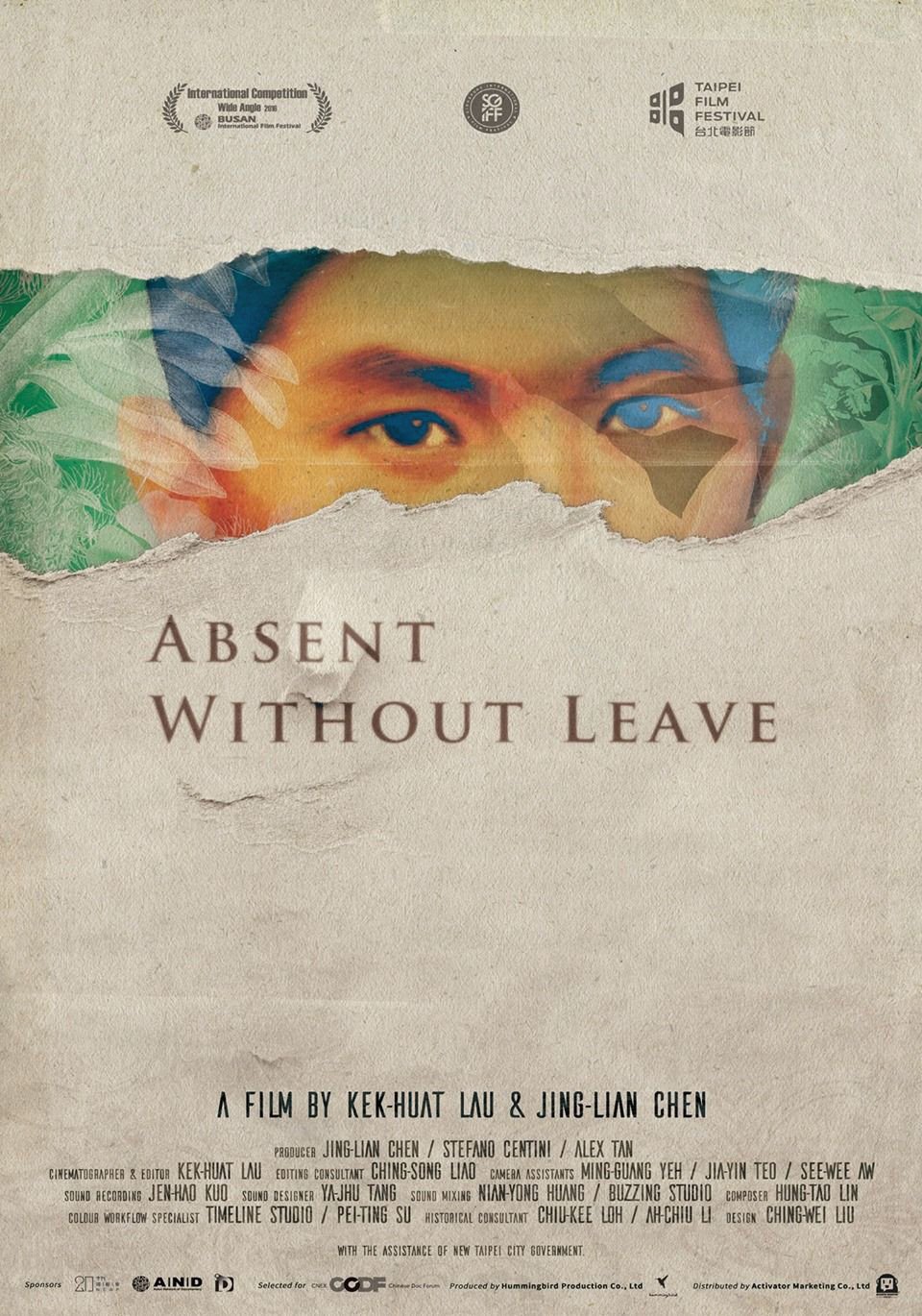

Lau has come a long way since then. Driven by a desire to understand his country’s unspoken past, Lau directed Absent Without Leave (2016), a documentary that followed his search into the lives of his absentee father and grandfather. Though the film brought Lau to the Berlinale Talents summit at the 2017 Berlin International Film Festival, it is still banned in Malaysia for putting a spotlight on members of the Malayan Communist Party.

The Tree Remembers (2019), Lau’s next documentary, contemplated Malaysia’s racial dynamics. A 2019 screening at the Freedom Film Festival in Kuala Lumpur drew a visit from plainclothes policemen, as the film had not been submitted for government approval. Even so, the rebellious screening offered a rare opportunity for inter-ethnic dialogue on censorship, as well as Kuala Lumpur’s “513” race riots of May 13, 1969, in which up to 600 civilians were killed, mostly Chinese Malaysians.

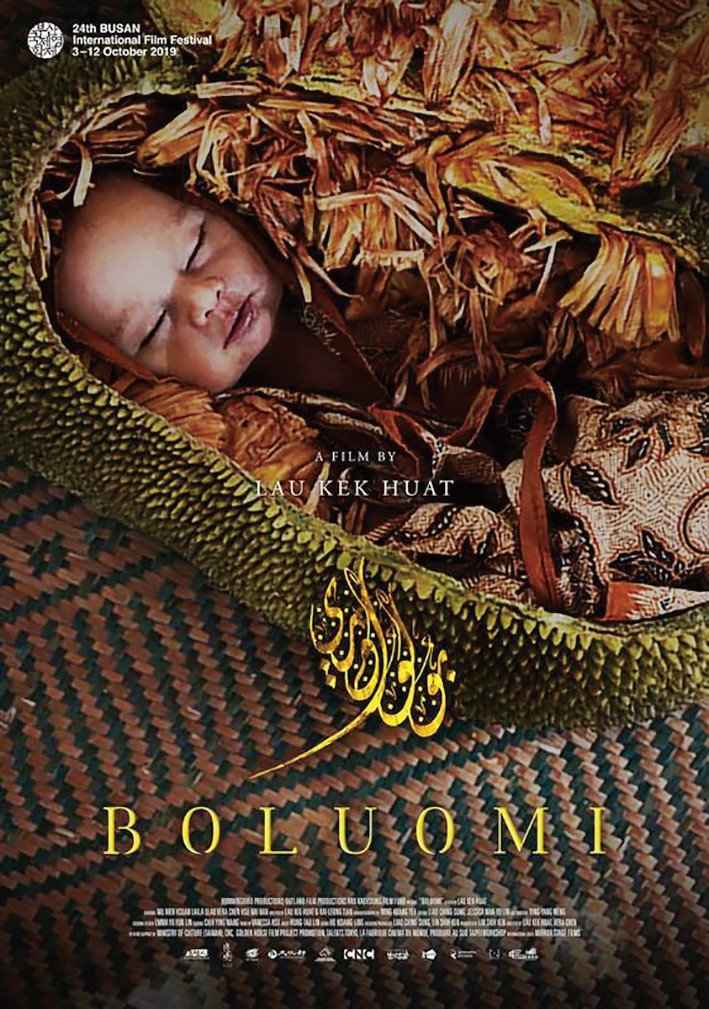

Lau’s first narrative feature film, Boluomi (2019), premiered soon after The Tree Remembers. It gained him nominations for Best New Director at the 56th Golden Horse Awards and for the New Currents Award at the 24th Busan International Film Festival. Characterized by curiosity, introspection, and daring investigations into history and identity, Lau’s career as a director is still something he has never taken for granted.

Your films give off a strong sense that, for you, documentary filmmaking is not an end goal, but rather a means to an end. Is that right?

Yes. It’s more like a process.

Before I got to know different types of documentaries, my impressions of documentaries were limited to the likes of National Geographic and the History Channel—they were dogmatic and always correct, summarizing all the facts and key points. Theirs was a rather conservative imagination of documentaries.

I don’t see my own films like that. My films are not about the so-called “absolute truth.” They only show what I come into contact with and learn about through the journey.

In making a documentary, you have to point a camera at people you have no control over. You accommodate them, or push against them, or wait for something to happen with them, but it doesn’t always go according to your will.

You have talked about keeping a critical mind toward anything claiming to be “right” or “just.” How did this way of thinking come about?

Perhaps I started diving into these thoughts when I began making Absent Without Leave.

Around the 40s and 50s, the Malayan Communists started to truly think about what Malaya was, what it meant to be a nation, how to find social balance, what justice entails…they were on the frontlines of that era.

Before I started my project, my previous education has always told me that Malayan Communists were terrorists. So as I thought about how to portray them in a film, I had to reflect on the matters they reflected on, too. That must have been when I started to ask: What on earth is right, or just? How do we evaluate that? It’s not like the Malayan Communists didn’t have a cruel side, but which facets should I show? It’s quite tricky, really.

Of course, as individuals, we tend to have our own principles. But if we take our own beliefs and force them on someone else, it will become violence—no matter how just, shiny, or beautiful that belief is.

So, I don’t like telling people that Absent Without Leave tells a story Malaysians “have to know.” There is no such thing as histories anyone has to know. As a person, you always have a choice in whether you want to know something, or not. Even if you have watched the film, you still can choose to believe it, or to argue against it.

To me, anything less is not true democracy or individual freedom.

If your films are not something everyone has to agree with or even know about, then what role do you see them playing in society?

Do you know Rumi, the Persian poet? He once wrote a poem, in which he said truth was a mirror which broke in heaven. The pieces fell into the world and everyone took one, which was fine, but some “looked at it and thought they had the truth.” Then they would try to force others to believe they held the whole truth.

When we look at Absent Without Leave, what’s really important is that we get to know the individuals in the film and their life stories: Mr. Ye, Uncle Li, my aunt and my mom, and so on. However, that doesn’t mean that their stories represent or explain the totality of Malayan Communists, or the totality of people in that era. We have to know that there are many more people out there, whose stories we haven’t gotten a chance to know.

I think it’s important to know that there’s way more that we don’t know yet. It makes us less arrogant or egocentric. Actually, if a documentary can make us admit, “Oh, so I didn’t know,” that would be an amazing achievement.

How do you actually “embrace the uncertainty?”

It was scary for me too in the beginning. I had plenty to worry about: Will this narrative work? Can I finish it? When you think about your work in progress like it has to be a finished product, especially like it has to bring you something, your worries would only grow.

I often tell myself that I don’t have to finish every film I set out to make. If halfway through I find that I am off, how about just dropping it?

Iranian director Abbas Kiarostami likened filmmaking to playing polo. Once the ball starts rolling, we’re all just chasing it around. To him that’s what filmmaking is—the director is not in control, but just going wherever the ball takes him. I see a sense of awe in this analogy, of awe toward life.

Do you ever worry that you might head to a relativist place where you can’t decide between different truths?

Of course you have to make decisions. Whenever you set up your camera, or whenever you decide to shoot, you are making a decision.

When we make a film about someone, we have to know what we have is memory, and not so-called history in an academic sense. We pick and choose what we remember. How frequently we call the event also affects how it becomes remembered.

But for those who are hurt or traumatized, it’s hard to make peace with truth. For them, the only way to continue living is to tweak their truths. When I present something like this, I constantly try to get closer to the individual, and to understand where such a drive or impulse comes from. Is it hinting at a more profound pain or fear buried deep inside them?

I find this a softness to be a capacity special to documentaries and films. A historian or scholar might throw away these tweaked narratives, but for a director or an artist, these are the exact moments where the depth of life reveals itself.

Can you give an example?

The Tree Remembers ends with an indigenous person describing their creation myth: When there was no one in this world, the god first created indigenous people. Then he created the Chinese, Malays, and Indians as their siblings.

Many are quite moved by this ending. But rationally it’s impossible for Chinese, Malays, or Indians to appear in the indigenous creation myth. The indigenous people were the earliest to come to the Malay Peninsula; they couldn’t have possibly met the others at that time.

When I shot this, I was fully aware that this was not the original creation myth, but there’s no need for me to expose this fact. Here’s what’s more interesting: Why did the indigenous people decide to include the Chinese, Malays, and Indians into their creation myth—and as siblings?

Without a written language, the indigenous people made editions to their creation myth, as a guide to understand how to place themselves within Malaysian society. This is the truth of their life. I think the fact that they chose to include others in the creation myth makes this a beautiful story.

In this film, you ruthlessly question whether you yourself have been a racist. That must have made you feel very vulnerable. Why did you do this?

In our racially divided society, our perspectives on many issues are boxed up in the framework of identity politics. So, some audience members would demand to know why I didn’t tell the story from a Chinese-Malaysian perspective. Why didn’t I talk about Chinese grievances and pain? And some Malay audiences would claim that I unfairly denounced the Malays.

I felt like it is hard for them to actually understand this film, or see it for what it is, because from the moment they walk in, they have been carrying a viewpoint—Chinese or Malay—that they are not willing to put aside.

Throughout history, no perpetrator of racial violence has thought of themselves as violators. They all believed they were the most serious victims. We have to understand that violence often finds seed in perceived, blown-up victimhood.

I find the line to be extremely delicate and something we need to be very careful about. Many initiatives in the name of rescuing memory or speaking up for the victims could end up unwittingly becoming sources of instigation.

What has your identity as Chinese or Malaysian brought to your creative expression? And what have you learned about your two identities through filmmaking?

I grew up in Johor Bahru, a southern border town where many locals work in Singapore. We watched Singaporean TV and celebrated Singaporean national day. In the eyes of northern Malaysians, we were less “pure” or “patriotic.”

In Singapore, people called us the “Federals” (because Malaysia used to be the Federation of Malaya). In their eyes, we spoke bad English and went there only for their strong dollars.

When I came to live in Taiwan later, they would just call me Southeast Asian—or they’d call me Malay because I am from Malaysia, though not all people in Malaysia are ethnically Malay.

Gradually, I realized I’d been living on shifting boundaries, so I naturally became sensitive to and interested in identity. But that also made it harder to pick a side, because I have seen that all these identities harbor subtle violent tendencies when facing unfamiliar outsiders.

Only politicians need to draw circles around these identities, and eliminate the diversity and agency within them. On the contrary, as artists, our job is to find these profound and delicate differences, clues, or bridges between people, and bring them back to light.

“Seeking Truths” is a story from our issue, “Dawn of the Debt.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine. Alternatively, you can purchase the digital version from the iTunes Store.

Seeking Truths is a story from our issue, “Dawn of the Debt.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.